If Tinne Van der Straeten wants to be remembered for one thing, it’s wind. In her office overlooking Brussels’ Northern Quarter, Belgium’s Energy Minister poses proudly with miniature turbines. Whole farms of them are stationed along shelves and windowsills, built out of Lego or rendered in crayon by her young daughter.

“I’m a bit obsessed,” she admits as she displays a special commission by a boutique chocolatier that she gifts to foreign colleagues. She’s not the only one – the diplomatic goodies have gone down a treat with Germany’s Vice Chancellor and fellow Green politician Robert Habeck, who has already eaten four.

But scaling up from confectionary to the modern monoliths of the energy transition is not a skill that ministers can master overnight, however great the appetite for clean electricity. With her sights fixed firmly on a 100% renewable energy system by 2050 and the ambition to triple wind generation by 2030, Van der Straeten displays an unflappable faith in the power of turbines to realise this vision.

It’s a drive that has delivered results: off and onshore wind together made up 18% of Belgium’s energy mix in 2023, up 25% from the previous year. The progress is impressive but to satisfy the demands of an increasingly electrified world, we’re going to need many, many more of these steel steeples.

These custom wind turbines make excellent diplomatic gifts. Credit: Orlando Whitehead / The Brussels Times

It’s certainly a mission that Van der Straeten is keen to own. With confident nods to the replicas dotted around the room, she reels off the successes of this sector like a triumphant manager listing their team’s palmares. Pride of place is reserved for the Princess Elisabeth Island – the world’s first energy island that will be a central hub for gigantic North Sea wind farms.

The project is notable on several fronts: in terms of raw power it will have a maximum output of 3.5 GW; Belgium’s nuclear reactors are both 1 GW capacity. In addition, it will link with UK and Danish high-voltage grids, serving as a gateway for international energy sharing that would mitigate the issue of how to manage excess and shortfalls. The CEO of Belgium’s high-voltage network operator Elia heralded the venture as the way to “endless amounts of renewable energy”.

There’s no doubting the Minister’s sense of achievement. For her, the project seems to signify much more than a cluster of metal masts spinning in a windswept expanse of ocean. It comes in the context of an EU-wide drive to ramp up off-shore wind, which until 2024 accounted for only around 10% of the bloc’s total installed capacity.

Belgium has set itself up as a standard bearer for this energy, with Van der Straeten and Prime Minister Alexander De Croo centre stage at the North Sea Summit in April last year – a high-profile gathering that assembled the leaders of Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, France, Ireland, and Norway in the coastal town of Ostend. Ursula von der Leyen also went along and the coalition pledged to collectively reach a colossal 300 GW in offshore capacity by 2050.

There's a bit of a theme to the office decorations. Credit: Orlando Whitehead / The Brussels Times

“This energy transition can’t be stopped. Not by one man, not by one nation,” Van der Straeten assures me. It’s a conviction that rides on billions of euros of investment, which besides severing dependence on fossil fuels will, she argues, feed industry in Belgium and nourish the economy.

But her assurance about the financial prosperity that renewables will bring has not hit home at all levels of politics and enterprise, with detractors unconvinced that the transition won’t just spell more volatility for businesses craving stability. Van der Straeten dismisses the notion that the energy revolution will imperil businesses as “simply a political framing”. And whilst she acknowledges that “energy is a lifeline for industries”, when sceptics question the reliability of a 100% renewable mix she insists that “we are managing supply better than ever.”

Rewiring the system

Optimism clearly is one thing there’s no shortage of. But it’s an enthusiasm that glosses over the scale of the challenge. Whilst the word “transition” implies a seamless passage from one energy to another, making that all-important pivot from the power sources of yore to the clean-breathing creations that underpin the Green vision is fiendishly tricky. Far more than just a question of ramping up renewable output and turning off the hydrocarbons, the leap to zero emissions will require a literal rewiring of how we manage energy flows.

In Belgium, domestic electricity consumption is set to triple as heat pumps and electric vehicles become our way of life. It’s a monumental shift that is over-simplified when we read about wind or solar projects that will produce enough to power whole towns, as if supply can just be installed where there is demand.

In fact, the success of the global renewable endeavour depends on the networks that ferry electricity to and fro – national and international grids capable of balancing surplus with shortage before circuits blow and the lights go out. This kind of systematic flexibility comes at a cost: Elia will spend €7.2 billion over the next five years to modernise the grid.

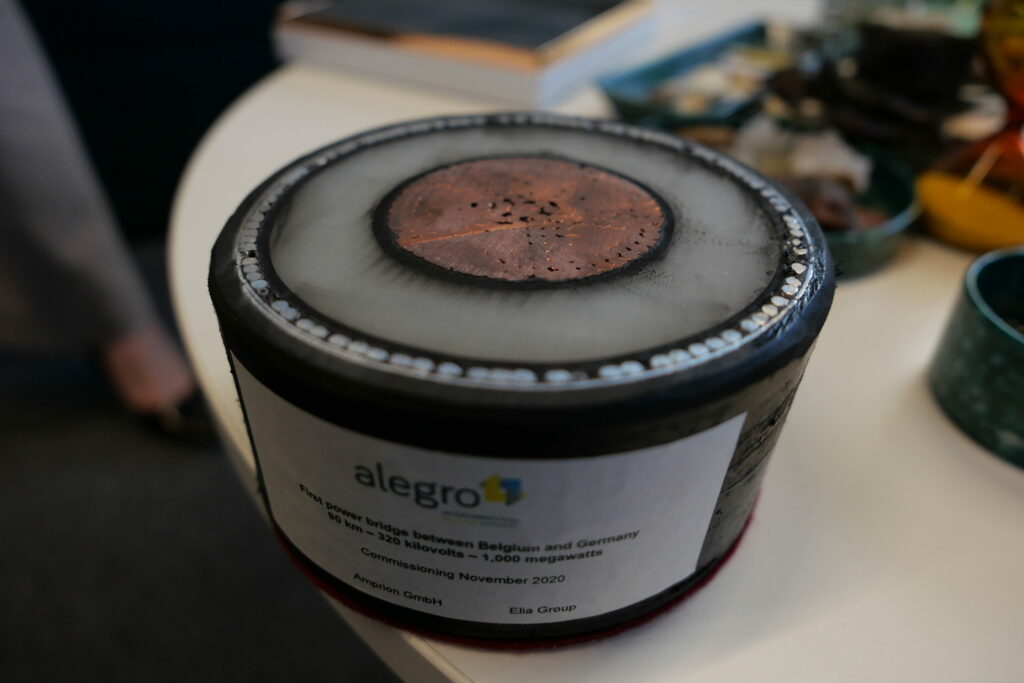

It’s this technical piece of the puzzle that is frequently forgotten when we imagine the green transition as swapping energy sources with little thought for the systems that facilitate this. “Security of supply isn’t only about generating enough electricity, it’s a question of exchanging it via interconnections,” Van der Straeten says as she points to a cross-section of the cable that links Belgium’s and Germany’s grid – the copper core as thick as my arm.

A cross-section of high-voltage grid cable Credit: Orlando Whitehead / The Brussels Times

But even at this early stage in the shift to clean power, Belgium’s systems are struggling. On a domestic level this has left homeowners disgruntled after installing solar panels only to find that the local grid can’t cope with the influx of power and they are unable to realise the electricity savings they had bought into.

The problem only grows when blown up to the industrial scale, which has stoked fears that the rush to renewables is jeopardizing the continent’s precious manufacturing base. Whilst green politicians evangelise about net-zero emissions in the near future, grave warnings of deindustrialisation abound among business heads.

The president of Germany’s leading industry body (the BDI) recently issued a damning verdict on the direction of energy policies: “Nobody can say with any certainty today what our energy supply will look like in seven years’ time. For companies that have to make investment decisions, that is absolutely toxic.”

Belgian businesses have levelled similar criticism at their Energy Minister, accusing her of pulling the plug on critical energies before the infrastructure is ready. It’s a reproach that has gnawed away at support for green parties Europe-wide and in Belgium has seen sister parties Ecolo (francophone greens) and Groen (dutch-speaking) tumble in national and regional polls.

But Van der Straeten is defiant, assured that the pummelling some predict in the June elections won’t materialise and she will remain in politics, Federal Minister or not. Some might see this as the fighting talk one would expect with just three months before the public cast their votes, but her resistance to critique is precisely what has so exasperated those who sound the alarm on losing Europe’s factories to where cheap energy is abundant, if not necessarily “green”.

Tinne Van der Straeten enjoys a close work relationship with Prime Minister Alexander De Croo

Nuclear U-turn

Much as Van der Straeten might wish that her legacy will be whirring propellers, it is nuclear that will define her term at the helm of Belgium’s energy office. For the past two decades the clock has been ticking for the country’s reactors since a 2003 law envisaged the cessation of nuclear electricity production.

Already the deadline had been pushed back but Van der Straeten was determined to see through this decisive chapter in Belgium’s energy policy. Up to this point in her career the former climate and energy lawyer had never disguised her distaste for fission and upon taking office in October 2020 she was again unequivocal in her commitment to the phase-out, the critical curtain call scheduled for 2025.

But the topic became only more fractious as it remained unclear how Belgium would plug the gap this would leave in the electricity mix (nuclear accounted for 41% in 2023). Many questioned the logic of dropping nuclear if it meant falling back on fossil alternatives. The closure of Doel 3 and Tihange 2 reactors in September 2022 and January 2023 (respectively) led to a 13% rise in CO2 emissions, as if the dogged efforts to pull out of this energy – much to the cheers of long-term nuclear opponents such as Greenpeace – was actually moving things further away from carbon neutrality.

The fiercest critics pilloried Van der Straeten for waging a crusade against the very power that could answer the need for security of supply without burning through climate objectives. Adding the expense and geopolitical inconvenience of gas into the calculation, it seemed that Belgium’s nuclear withdrawal would be an act of economic hara-kiri.

Greenpeace protesters unroll a banner on the Atomium in demonstration against the production of nuclear energy. Credit: Belga / Atomium ASBL

In her defence, the Minister paints nuclear as a costly option with risks that can be avoided with solar and wind. But whilst it is true that these renewables have become far more affordable, one gets the sense that Van der Straeten’s truck with nuclear transcends price comparisons. Far more than an impartial economic assessment, the distrust of fission long predates her political career.

She recounts CND marches as a student and is emphatic about the waste: “Enough to fill six Olympic swimming pools,” she sombrely tells me. “And we have to manage it for millions of years, for a longer period than the Pyramids have existed in Egypt.” Her tone echoes the doom-mongering of anti-nuclear militants who evoke a barren wasteland akin to the scenes of post-apocalyptic fiction.

Indeed, I’m prompted to ask for specifics as she tells me that “A technology that gives us waste like that isn’t much different from energies that emit greenhouse gas; we can’t continue to emit CO2, because that will stay in the atmosphere for so many years. Nuclear also poses a long-term problem.”

Can we really claim such an equivalence between these energies? “Why is it not the same?” comes the response. Unsure if this was rhetorical I point out that nuclear is not a fossil energy and comes without the trouble of greenhouse gasses that are quietly cooking our planet. It’s a quibble we leave unsettled.

Leaving ideals at the door

Yet it would be too simplistic to write Van der Straeten off as a dyed-in-the-wool nuclearphobe; at least in her official capacity this really isn’t a tenable position. A term in any of Belgium’s federal offices is an education in suspending your ideals during hours of negotiating. Ministers might scream and kick but in this country nothing moves if individuals aren’t prepared to come to table.

And the imperative to exchange passion for pragmatism has rarely been greater than during Van der Straeten’s mandate, with industry and households of all political persuasion clamouring for certainty and deliverance from crippling energy bills. The aversion to atom smashing was necessarily put on the back burner as Belgium pulled out all the stops to take back energy control.

Nowadays the Minister has tweaked her tune, insisting that “it’s not about nuclear in and of itself” but rather balancing short-term concessions with long-term goals. Touching on the exceptional series of events that in recent years have forced governments to ditch their A-Plans for contingencies they had never imagined, Van der Straeten describes the early days and weeks after Russian tanks rolled into Ukraine and her responsibility went from being a technical matter to a strategic one.

“All of a sudden we were monitoring gas flows and what was happening on the border. We were suddenly addressing everything from a security perspective. We had a crisis plan but it was designed in a time of peace… it had never been tested.”

Puzzles of nuclear plants were distinctly absent. Credit: Orlando Whitehead / The Brussels Times

It was a crunch moment that required coordination at the EU level to cap gas prices and soon put Belgium at the centre of EU gas management, with the Zeebrugge terminal becoming the third biggest LNG supply port in the world. The overwhelming majority of the gas is not for Belgian consumption but is piped elsewhere in Europe – “Four or five times our national need went to Germany.”

Van der Straeten has previously regretted this arrangement, which makes gas a crutch for industries not adapted to run on renewables. However she accepts the role Belgium plays in Europe more broadly and takes pride in the diplomatic achievement.

With Belgium’s two remaining reactors just extended for another ten years and Brussels hosting the inaugural Nuclear Energy Summit, one might contest that Van der Straeten will go down as another Energy Minister forced to settle for an imperfect middle ground. The winds of change are certainly growing, but for all her efforts they haven’t yet blown away the need for nuclear.

She maintains that this is neither good value nor sustainable but accepts that security of supply is the order of the day, preferring to portray her latest association with nuclear one of necessity and ministerial responsibility. I wonder what the future holds for green parties once their USP (carbon neutrality) is no longer unique. “Then we go on holiday!”

The optimism prevails and Van der Straeten points to a puzzle she does between calls. The picture isn’t yet complete, but soon it will display a sea of turbines.