The question I’m confronting thanks to my newly-acquired legal obligation to vote in Belgian elections is the following: who, or what, am I voting for, or against?

It may seem to be an obvious question – indeed, the only question – but this most complex of political systems raises many more questions than it answers.

When I was a lad back in Britain, and my dad volunteered to drive little old ladies to the nearest polling station on the big day, it all seemed so simple: in the run-up to a national election, three kinds of people showed up on the doorstep.

In no particular order, one would be a Conservative candidate in a suit and tie and sometimes a bowler hat. Another was a Labour candidate in a tweed jacket and a flat cap. The third was a Liberal in a V-necked sweater and corduroy trousers. They were almost always men and they came bearing leaflets full of promises.

As I understood it, the idea was to vote either for the local candidate who promised to do the most for our area (from higher quality potholes in the roads to lower street parking tariffs), or for the one representing the political party of the person the voter wanted to see become prime minister. If you were lucky, those two ideals merged into one.

Allowing for many sartorial, social, stereotypical and cultural changes, that remains the same, thanks to the Brits still only having four governments.

Over here, of course, there are six governments, which is one of the perks of living in a country where a coalition culture is the result of having to run a multi-layered political federal system.

The trouble is, the nature of such an arrangement makes it virtually impossible to second-guess the final election result, even if you’ve got a maths degree and a crystal ball, which I haven’t.

© Lectrr

On the positive side, without such a system, Belgium would not be the proud owner of two world records for functioning for the longest time as a nation without an elected government.

Admittedly it’s not a fiercely contested sport, which is probably why Belgium felt obliged to challenge its own original record of being government-less for 541 days after the June 2010 election.

The re-match, triggered by the collapse of then-Prime Minister Charles Michel’s administration over coalition clashes in December 2018, smashed the 541 target to reach 652 days – running through the June 2019 elections – with stability being restored in October 2020.

Unnoticed instability

A lot of us didn’t notice much instability at the time, and certainly no insurrection, so when a television crew came into view one sunny day in late summer 2020, I gladly accepted an invitation to pontificate from my pavement table outside a coffee bar about the state of the nation.

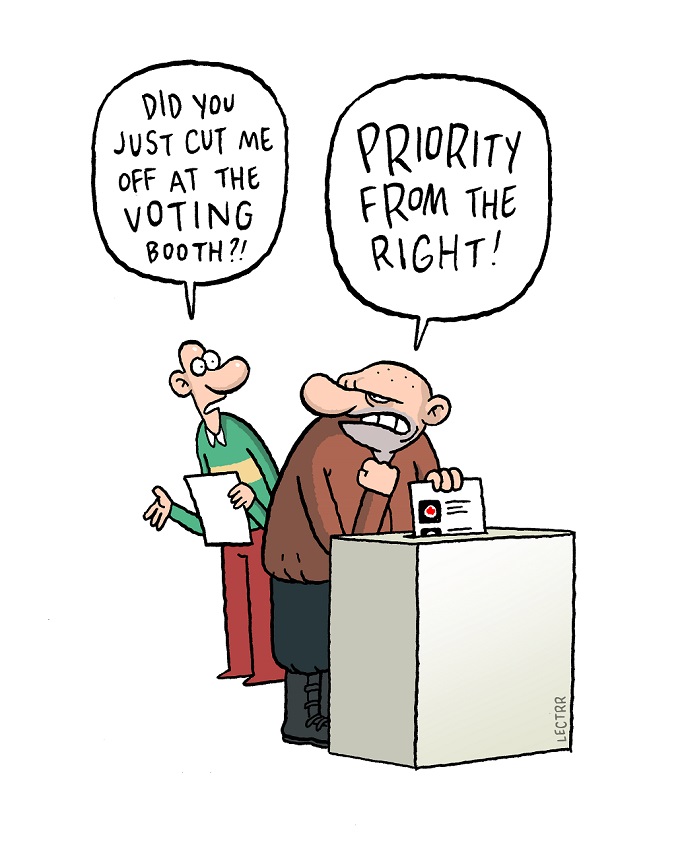

I made some positive remarks about the indefatigable Belgian ability to navigate rudderless through some impressive political storms, and then added that as long as the traffic lights were still working and the Belgian motorist still retained his and her precious ‘priority from the right’ rule, then all was well with the world.

Which brings us back to the present day, and my decision to put my vote beside the name of whichever candidate or party is prepared to push hardest to ditch once and for all a crazy law, not of Belgian origin, which has plagued drivers on the continent for nearly 100 years.

It was introduced across Europe after an international conference in Paris in 1926 about how to cut road accidents, and, in those early days of simpler driving it might have seemed very sensible.

But on increasingly packed roads, where speeds have crept up over the past century, it only causes stress and confusion because any traffic emerging from a side road to your right has priority, even if the road you are on is a fast highway and the road to the right is little more than a narrow lane.

The rule doesn’t apply if the side road has a ‘Give Way’ sign or similar markings painted on the road itself, but that’s not always clear to the driver on the main road until it’s too late.

Until March 2007 the worst confusion was caused by the fact that the law stated that if the vehicle coming out of the side road stops, it loses its priority. So the motorist on the main road had to calculate whether the car it could see slowing down was actually going to continue turning into the main road or slowing down to stop and cede priority.

If anything, the confusion was multiplied after March 2007 because since then the driver emerging from any minor road which doesn’t have ‘Give Way’ signs or markings keeps priority even after slowing down or even stopping for a moment or two.

Human liberty at stake

Sheer self-preservation may play its part in preventing some spectacular smashes, but some drivers would rather risk death than abandon their right, indeed, legal obligation, to move out into the path of fast-moving traffic which should have stopped.

Many notable figures down the years have raised the issue of scrapping the whole thing, including, more than 25 years ago, the then-EU Transport Commissioner, Neil Kinnock, former leader of the British Labour Party.

He condemned the rule as “an offence against the security and liberty of the human race,” which might seem a bit of a stretch, but which not surprisingly created some headlines, including this gem: “Priority from the wrong”.

Inevitably journalists asked the Commissioner if his outburst was caused by a car accident in Belgium involving him or his wife. He told MEPs: “If that were the case, I would be even more incandescent than I am now.”

So I’m not alone in this battle. If anything, I’m way behind the curve, especially as many Belgian municipalities have already voted to scrap the priority rule and introduced new rules to clarify that cars on side roads have to give way, regardless of signage.

I suspect there will have to be a debate on the subject of what, precisely, is the definition of a side road before this campaign goes national.

For political balance, I should say that, while the motoring organisation VAB agrees that priority from the right should be scrapped everywhere, the Belgian Institute for Road Safety points out, not unreasonably, that the rule works well in built-up areas.

Anyway, that’s enough of that, but thank you for listening to a rant which has at least cleared my mind about which political bandwagon to support with my precious vote. All I have to do now is identify which election candidates are likely to work hardest towards fulfilling my political agenda.

It’s clearly not going to be as easy as it looks. I’ve just asked a search engine a simple question: “Which Belgian election candidates support priority from the right?” The immediate response has been to direct me towards an article headlined “Elections 2024: The rise of the far right in Belgium”.

This politics stuff is more complicated than I thought.