The European External Actions Action Service (EEAS) announced recently a round of nominations of new heads of delegations abroad. Among them was the current EU special representative for the Belgrade – Pristina dialogue, Miroslav Lajčák, who was appointed to ambassador to Switzerland after the summer.

This sparked rumors that the Slovak diplomate had to leave because the dialogue on normalisation of the relations between Serbia and Kosovo had failed. In fact, his four-year term will expire soon. EU’s lead spokesperson for foreign affairs, Peter Stano, said on Monday that Lajčák had the confidence of the member states and that the vacant post will be published after internal procedures.

“"There was never an argument, I never planned to leave or stay longer,” Lajčák was quoted in media. “It is logical that with the new leadership of the EU, it is also good to start a new phase of the process. So, until August 31, I am fully responsible and fully committed to this process.”

But there is no denying by EEAS that the EU-facilitated dialogue between Serbia and Kosovo so far has failed, despite attempts by the EU to revive it, because of obstruction by both countries and violent tension in the northern part of Kosovo which is populated by a Serbian minority.

The latest attempt was last year’s agreement between the two countries to normalise their relations to pave their way for EU membership. As previously reported, the implementation of the agreement has stalled.

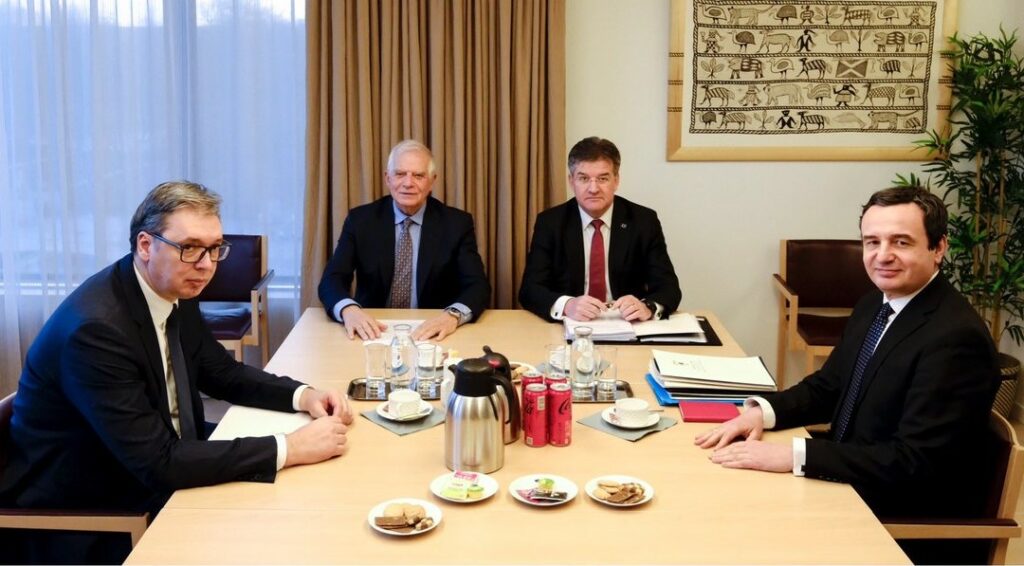

The dialogue is chaired by EU’s foreign policy chief, High Representative Josep Borrell, supported by Lajčák. In February 2023, Borrell said that the two Western Balkans countries had expressed their readiness to proceed with the implementation of the agreement but that further negotiations were needed to determine specific implementation modalities of the provisions.

Those talks took place the following March in Ohrid, North Macedonia, where the parties agreed, at least according to Borrell, to an annex to the agreement, which became an integral part of the agreement. They committed to honour all articles of the agreement and the annex, and implement all their respective obligations stemming from them expediently and in good faith.

But the documents were never signed by Serbia’s President Aleksandar Vucic and Kosovo’s Prime Minister Albin Kurti. Despite crisis-management meetings, the EU could not convince them to start implementing the agreement. “This is very regrettable, and it speaks volumes about the Parties’ true commitment to normalisation of relations – or rather the absence of it,” Borrell complained.

Strong mandate and political will missing

Notwithstanding the non-signature by the parties, the EEAS claims that it is a legally binding agreement, even more so after it has become part of the benchmarks and commitments of the two countries in their accession path to the EU.

The EEAS announced after the latest foreign affairs council meeting that, “Serbia and Kosovo have accepted that their respective obligations stemming from the Agreement from Path to Normalisation will become integral parts of their European integration paths”.

“The Implementation Annex concluded in March 2023 in Ohrid also reflects this commitment by the Parties. We welcome the adoption by the Council of the updated interim benchmarks including the Agreement in Chapter 35 of the accession negotiations for Serbia on Monday 22 April.”

In practice, not much seems to have changed and the spokesperson admitted that the EU cannot force the parties to implement the normalisation agreement. He repeated that the EU is there to help them to bridge their differences but that it will never succeed if they refuse to go down the path of compromise.

It is not the fault of the special representative that the dialogue failed if the parties do not negotiate in good faith. “Lajčák is an experienced and knowledgeable diplomat who knows the sensitivities on both sides,” a Western Balkans dispute settlement expert told The Brussels Times on the condition of anonymity.

“He actively pursued an agenda, already before Ohrid and the normalisation agreement,” he added. “Before his time, the dialogue meetings were often merely meetings with hardly any agenda and hardly any results. But as any mediator, he depended on the good-will of the parties and that was missing for most of the time.”

What lessons can be learned? “An agreement that is forced on parties is very unlikely to work. This is a fundamental principle in conflict resolution. Parties must be convinced that what they agree to provides for mutual gains and results in a win-win situation.

“If the parties prefer to make confrontational use of a conflict situation, there will not be any sustainable solution. What also needs to be taken into account is that there are five EU member states that have not recognized Kosovo, so any mandate for the Belgrade-Pristina Dialogue tends to be limited for the time being.” He was referring to Spain, Slovakia, Cyprus, Romania, and Greece.

Peter Stano, the spokesperson, said that the EEAS is constantly monitoring the situation. Is there a need for an evaluation of the role of the special representative before appointing a new one?

“The member states should have an open discussion as to what extent they want to develop and enforce the Ohrid Agreement,” replied the expert. “Silent diplomacy is always helpful and this is what the representative should and will be doing but he or she also needs a strong mandate and the backing of the US behind the scene, as has been the case.”

M. Apelblat

The Brussels Times