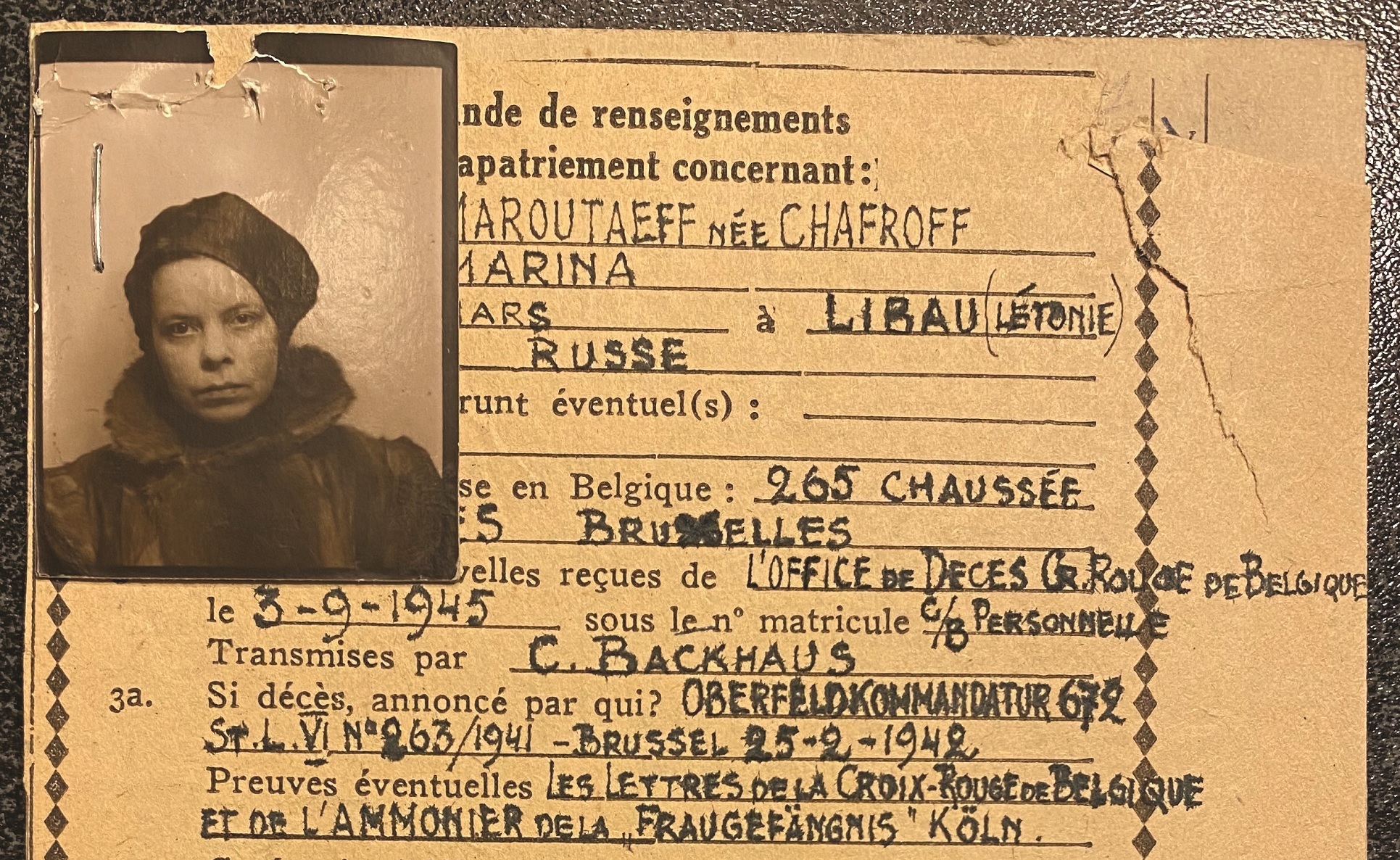

War heroes come in all shapes and sizes. If, as it is sometimes said, true heroism is the urge to serve others at whatever cost, then it fits Marina Chafroff, a Russian émigré living in Brussels during the Second World War.

She is the real-life hero of author Myriam Leroy’s latest book, Le Mystère de la femme sans tête (The Mystery of the Headless Woman), which tells of how Chafroff joined the Belgian resistance following the Nazi occupation and paid for it with her life. Her brave actions have, until now, been largely overlooked by history.

From the outset, the married mother of two took enormous risks.

Determined to outwit the strict news censorship rules, she would secretly transcribe radio bulletins from her homeland, invaded by its former ally when Adolf Hitler launched Operation Barbarossa in June 1941. Despite the risk of arrest, she would post translations all over the city.

But Chafroff felt she needed to do more and her acts of resistance soon took an extremely violent turn.

On December 7, 1941, she approached a German officer on Avenue Marnix near the Porte de Namur, pulled out a knife and killed him.

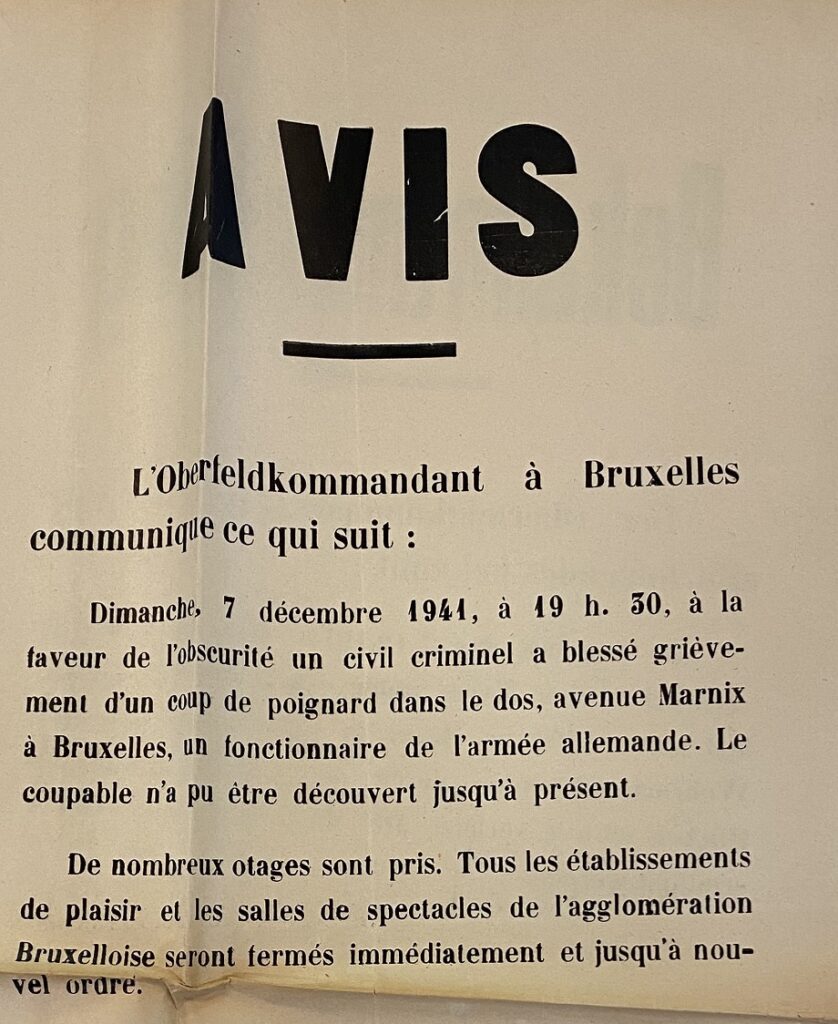

In response, the occupying force took 60 hostages and threatened to execute them if the guilty party failed to surrender. Chafroff decided to turn herself in – and, on the way, stabbed another German officer.

The poster warning printed after Chafroff killed a German officer

The 33-year-old was condemned to death by firing squad but, following her transfer to Germany, she was instead beheaded, supposedly on Hitler’s direct orders. While most such sentences were carried out by guillotine, she was beheaded with an axe, probably by the Nazi regime’s prolific executioner Johann Reichhart.

That’s the widely accepted version of events. However, Leroy, an accomplished journalist, screenwriter and playwright, discovered much more about Chafroff during research for the book.

Cemetery discovery

The idea for writing it came about during the pandemic after Leroy had arranged to go for a walk with a friend. They agreed to meet at Ixelles cemetery, where they could safely remove their masks and escape the confinement for an hour or two.

“As we were walking, we came across a row of identical graves, all World War II martyrs,” says Leroy. “Under each name were the words ‘Death by firing squad’. But then, on the last grave, we saw a woman’s name for the first time – Marina – with a single word underneath: ‘Decapitee’. I never thought I’d write a book about the Second World War, but when I saw that I knew I had to find out more about her.”

Chafroff's grave

As she pursued her research, a succession of seemingly chance events and coincidences made Leroy feel like she was meant to tell Marina Chafroff’s story.

Marina Chafroff as a young child

“I found out she lived just a few steps from where I live. She rented a room for her resistance work right near a place I rented to make a documentary. She spent time in the village of Morsain in Walloon Brabant, close to where I grew up – and where I had a Russian boyfriend.

“Then I came across a letter she sent from prison in Cologne to her mother asking for copies of a magazine called Les Bonnes Soirées, which I had never ever heard of. A couple of days later, at a secondhand store, I came across a pile of that very magazine.”

Despite feeling a strong sense of affinity with her subject, Leroy nearly abandoned the project several times.

She was frustrated by gaps in the story and her sources, including members of Chafroff’s family, often had different recollections of what happened. For instance, Marina’s younger son Vadim, now 84, insists that his father, rather than his mother, attacked one of the German officers.

What is not in dispute is that Chafroff – who was born in 1908 in Liepāja, which is now part of Latvia - was beheaded by the Germans and that, despite being a devoted mother, refused the clemency she was offered, leaving her two very young children as de facto orphans since their father was often absent.

Given the lack of a complete narrative, Leroy decided to create a work that mixes fact-based detail with her personal account and intuition. She has changed the chronology of events, invented some characters, and put imagined thoughts into their heads.

Historical novel

But all the documents she cites and statements quoted from people she spoke to are authentic. She carried out research in Belgian, German, Czech and Red Cross archives dating from the war. As well as Chafroff’s family, she listened to interviews conducted with Marina’s husband by Ramon Puig, a retired European Commission official who had also come across her grave more than a decade ago.

“One could call the book invention or imagination except that I had the impression that someone was feeding me the lines and that I didn’t pull anything out of nothing,” Leroy says.

“When I use my personal history, it is because it resonates with Marina’s. So this is a historical novel, an investigation, and a contemporary nonfiction narrative which tries to establish political parallels between today and 80 years ago.”

Leroy is convinced that history has largely overlooked Chafroff’s role in the resistance solely because she was a woman. “Press accounts at the time, for instance, don’t mention the possibility that she was acting politically but rather was overcome by her hormones and that it was a crime of passion,” she says.