What was the Second World War like for Brussels? At first, it looked much the same as during peacetime. Although war was declared between the major European powers in September 1939, there was limited fighting on the Western Front.

Belgium, like France, the Netherlands and Britain, was engaged in the Phoney War: armies were mobilised, diplomatic and economic ties with Nazi Germany were curtailed, but there was almost no military action. Belgium was a country caught between war and peace, between hope and fear.

That changed on the morning of May 10, 1940. Sirens sounded shortly before dawn. Radio programmes were interrupted as news broke of a German invasion. The Evere airfield and several neighbours in the capital were bombed. Some 41 people were killed and more than 80 injured that day.

After eight months of waiting, the war was now very real. It came from the sky, a phenomenon that Brussels had not previously experienced. Panic spread as the bombings continued in the days that followed, with many fleeing the city. Long feared, the German attack convulsed the capital with terror.

Unlike in August 1914, at the grinding start of the First World War, the conflict this time was immediate. As in 1914, the parliament’s two chambers were assembled the same day, while King Leopold III met the head of the army. But this time, there was none of the patriotic fervour of the previous generation: everyone remembered the horrors of war and the civilian massacres of the Great War.

In the days that followed, as the aerial assault continued, Brussels began to empty. Residents and businesses left, newspapers stopped printing and only the radio continued broadcasting – but until May 15. News still got out and rumours spread.

People heard that the Dutch succumbed after five days of fighting, and assumed that the Third Reich’s army was invincible. Even when British soldiers from the British Expeditionary Force passed through the capital, it only heightened the sense of dread amongst civilians, who feared they could get caught in the middle of a massive conflict.

As the bombing intensified, the Belgian government abandoned the city, the ministers entrusting power to the secretaries general, the senior civil servants who would become the interlocutors with the invaders. On May 18, Brussels was occupied, just eight days after the attacks started. Ten days later, the Belgian army surrendered.

The ministers, now in exile in France, were unable to define a strategy – it was not until October 1940, after they had moved again, to London, that an embryonic government-in-exile was formed. They declared that Belgium would continue the fight against Nazi Germany alongside the Allies.

Funeral procession at Place Flagey 10 September 1943

King Leopold III, however, remained in Brussels. It was he who had controversially ignored ministerial advice and surrendered the Belgian army. He visited Adolf Hitler soon after but was kept a prisoner in Austria – and in 1941, while a captive, married London-born Marie Liliane Baels (the ‘Royal Question’ about his wartime conduct would dominate post-war politics: he won a referendum on his return to the throne, but the result was so narrow that in 1951, he abdicated in favour of his son Baudouin).

Occupation and collaboration

After Belgium’s capitulation, a German military administration was installed in Brussels. Led by General Alexander von Falkenhausen, its authority extended not only across Belgium but also to the French departments of Nord and Pas-de-Calais. Most of the German occupying forces based themselves in the capital, requisitioning buildings like the Residence Palace for their officers and officials.

The German occupiers recognised that their authority would be enhanced if they secured the symbolic support of the people – even if the people in question were collaborators.

Two key local political parties emerged as the main forces for collaboration. For French speakers, it was the Rexist Party, or Rex, a far-right, Catholic group led by Léon Degrelle, who would later join the Waffen-SS, the Nazi paramilitary force (he escaped to Spain after the war, but was court-martialled and convicted in absentia. In exile he denied the Holocaust and continued glorifying the Nazi regime).

Léon Degrelle leads a march of his Rexist group

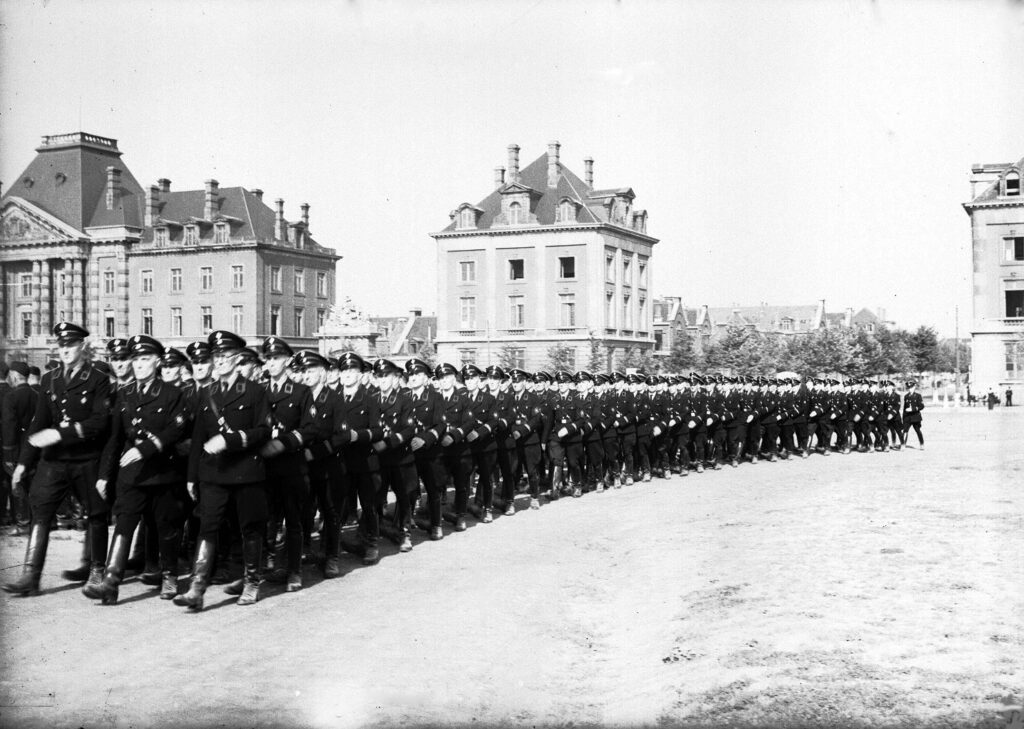

For the Flemish, it was the Vlaams Nationaal Verbond, or Flemish National League, which pushed for a ‘Greater Netherlands’ that would unite Dutch speakers in Flanders and the Netherlands. Both Rex and the VNV would parade through the streets of the capital and would even offer up volunteers to fight alongside the Germans on the Eastern Front against the Red Army.

The Brussels authorities were managed by a college of mayors and aldermen, with liberals as the dominant political force, and for the first two years of the occupation, they managed problems collectively through an informal body, the Conference of Mayors of Brussels.

It was led by the Brussels City mayor, who was the intermediary with the occupiers, even if, upstream decisions were taken collectively by the mayors. This was Joseph Van De Meulebroeck until June 1941, when he was arrested and replaced by a more pliant mayor from the Catholic Party (Van De Meulebroeck would return in 1944 and remain mayor until 1956. The Catholic Party would be dissolved after the war).

However, relations between occupiers and the Brussels authorities soon deteriorated. In September 1942, the mayors were dismissed and ‘Greater Brussels’ was set up, with the capital run under the principles of the New Order, the Nazi system of reorganising the occupied European territories under racial lines.

At the head of Greater Brussels was the Catholic Party’s Jan Grauls, a Flemish former civil servant at the Ministry of Education and interim governor of the province of Antwerp. The symbolic creation of Greater Brussels was interpreted as a victory for the Nazi collaborators and those seeking Flemish control over the capital.

Everyday life

What was everyday life like for the people who remained in Brussels? Rationing was introduced in the autumn of 1940, with designated food and drink only available through ad hoc stamps. Residents with family in the country tried to get extra supplies, while others began planting crops in the Brussels parks.

For those who could afford it, there was the black market and the infamous ‘Rue des Radis’ in the Marolles district. It was relatively easy to hide food in the event of an alert, mainly thanks to the vents that Brussels houses have, but items from clothes and shoes to fuel and spare parts became harder to find.

Meanwhile, the Brussels resistance moved slowly but slyly to block, delay, undermine and confound the occupiers. They had struggled in the first few months of the occupation, with just a handful of them believing that the Germans could be beaten. With only Britain holding out against the Nazis in Europe, hope was in short supply. But after the torpor and despondency of the summer of 1940, there was a slow awakening of patriotism – and anti-fascist defiance.

November 11, 1940, marked a turning point when Brussels patriots commemorated the German capitulation of 1918 at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier on Rue Royale – a gesture that predictably aroused the ire of the Nazi occupiers.

The banned march at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, Brussels November 11, 1940

Resistance groups and networks gradually emerged. Underground newspapers appeared in Brussels, more than a third of the 675 titles listed for the whole of Belgium. The urban fabric provided ideal conditions to share clandestine press, with schools and administrative services particularly adept at distributing papers.

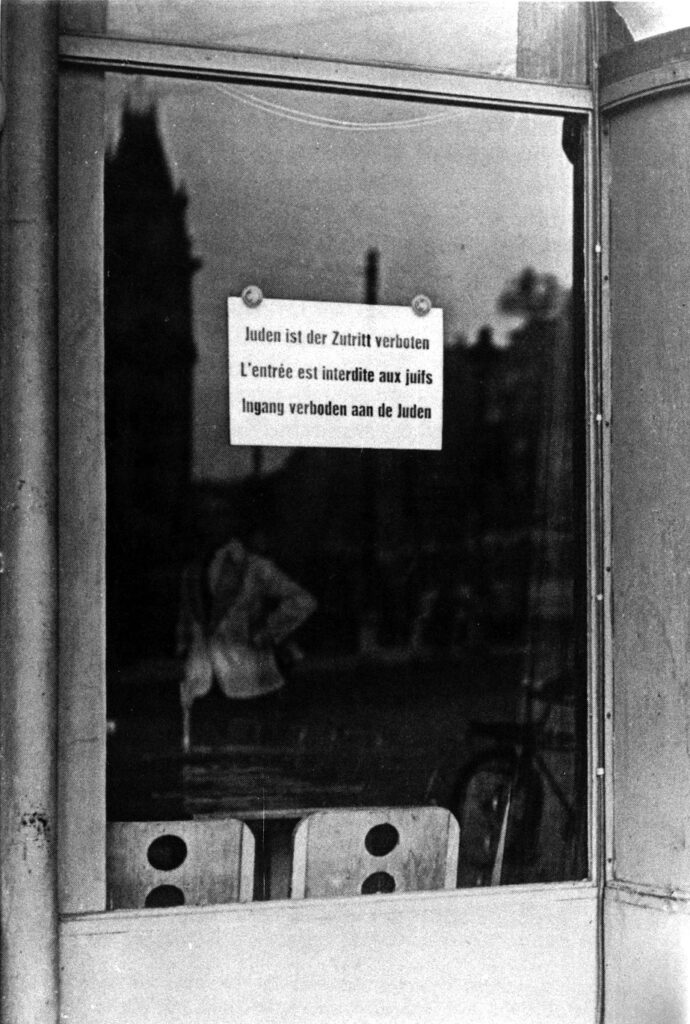

The ever tightening measures against jews included banning them from certain shops

The resistance also arranged rescue operations, notably for Jews hiding from the Nazi occupiers, most of whom lived in Antwerp and Brussels. However, the fate of Jews varied according to their location: 65% of those in Antwerp were deported and killed, while in Brussels, the rate was 37%.

These differences were partly related to the attitude and behaviour of the local authorities (the mayor of Brussels refused to hand out yellow stars in May 1942,). It was also linked to the location of the Jewish population on the territory, their roots in the local community, their relationship with the wider society, and to the local groups who sprung up to save them.

Volunteers leaving for the Eastern front

But the Germans nonetheless remained the occupying force, exerting power through military might. Their control of the capital, upheld by local collaborators, bred a relationship with violence. There were many attacks against Germans in Belgium: more than half (54.84%) in Brussels while this proportion was only one in six (16.42 %) against collaborators.

Acts of violence grew over time. In the summer of 1942, the occupiers began actively hunting Jews as well as resistance fighters and anyone trying to escape forced labour. Ironically, there was also danger from the Allies, whose strategic bombings in and around the city added to the sense of anxiety –sometimes hitting civilian targets.

As the war headed towards its inevitable endgame, daily life became increasingly difficult, with the nervous occupiers on the lookout, collaborators feeling cornered and resistance fighters becoming increasingly reckless.

By July 1944, the German military administration was replaced by a civilian administration under the authority of the SS. Officials were handed clear directives: the resistance must be broken by any means necessary, including counter-terror. The final days of the occupation were characterised by a spiral of violence and counter-violence.

Liberation

Events sped up at the end of August 1944. Paris was liberated on August 25. Brussels hoped and expected it would be next. For collaborators, it was time to flee. Before leaving the city, the Rexists launched a final wave of looting, raiding jewellery stores across Brussels. The German occupiers also descended into a vicious frenzy as they continued to round up anyone resisting forced labour.

But by the end of the month, both the Germans and the collaborators had fled Brussels, taking any road out of the city as they headed to the Reich. Before departing, some tried to sabotage the city, on September 3, 1944, a few hours before Brussels was liberated by the Allies, German soldiers blew up the dome and the basement of the law courts, the Palace of Justice.

The liberation of Brussels by the allies, September 1944

There was a power vacuum and a sense of chaos in the moments before the arrival of the Allies and the Piron Brigade – the remnants of the Belgian army reconstituted in London – to liberate the capital. But when they arrived, Brussels greeted them with elation: British and American soldiers were embraced, locals clambered on tanks and Jeeps, and crowds celebrated jubilantly.

It was not the end of the affair: Brussels still had to wait for the return of those held in the shrinking Reich: prisoners of war, forced labourers, political deportees and racial deportees – including the King (he did not immediately return to Belgium, naming his brother, Prince Charles, as regent while he moved to Switzerland). It would be several months before their return – or non-return.

By the time Germany surrendered on May 8, 1945, Victory in Europe Day, the people of Brussels celebrated again. Their wartime ordeal was finally over, although the scars of occupation would remain.