Belgian tourists wandering through Bangkok are sometimes surprised to come across an elevated viaduct called the Thai-Belgian Bridge. For more than 30 years, the overhead iron flyover has carried traffic above a busy intersection in the heart of the city. But before it was constructed to bring relief to Bangkok’s traffic congestion, the viaduct ran above Avenue Leopold II in Brussels.

Built in Brussels in 1958, the iron flyover was originally intended as a temporary solution to an urgent problem. The country at the time was in the middle of an economic boom that would last from 1945 to 1975. Les Trentes Glorieuses, the Thirty Glorious Years, it is often called.

The politicians behind the 1958 Brussels World's Fair, Expo 58, were determined to show the world that Belgium was a dynamic, modern country. They found inspiration in the United States where the private car had created a new lifestyle. The husband worked in the city, the wife stayed at home, and the car was the way to get around.

But Brussels was an old European city with narrow streets that soon got jammed with cars. The Belgian bureaucrat Henri Hondemarcq, head of the Highways Administration in the Ministry of Public Works, had already in 1949 come up with a bold plan to turn Brussels into “one of the most important road intersections in the West.”

Not many people recognise the name, but Hondemarcq profoundly changed Brussels. He campaigned to get the United Nations to recognise Brussels’s role as a key European transport hub when it launched the network of E motorways. As a result, the city now sits at the centre of a web of E routes – the E40, E19 and E411. The light cast by these motorways after dark is visible from deep in space.

The obvious next problem was how to deal with the huge volumes of traffic entering Brussels. Hondemarcq decided the answer was to create three concentric ring roads around the city along with a network of arteries radiating out from the centre.

It might have taken years to implement the scheme, given the ingrained complexity of Belgian bureaucracy. After all, the construction of a rail tunnel through the city had taken 40 years to complete. However, Expo 58 offered a unique opportunity to rush through the plan. In just three years, the city built most of the inner ring around the old city along with parts of the second ring and the initial section of the E40 motorway to Ostend.

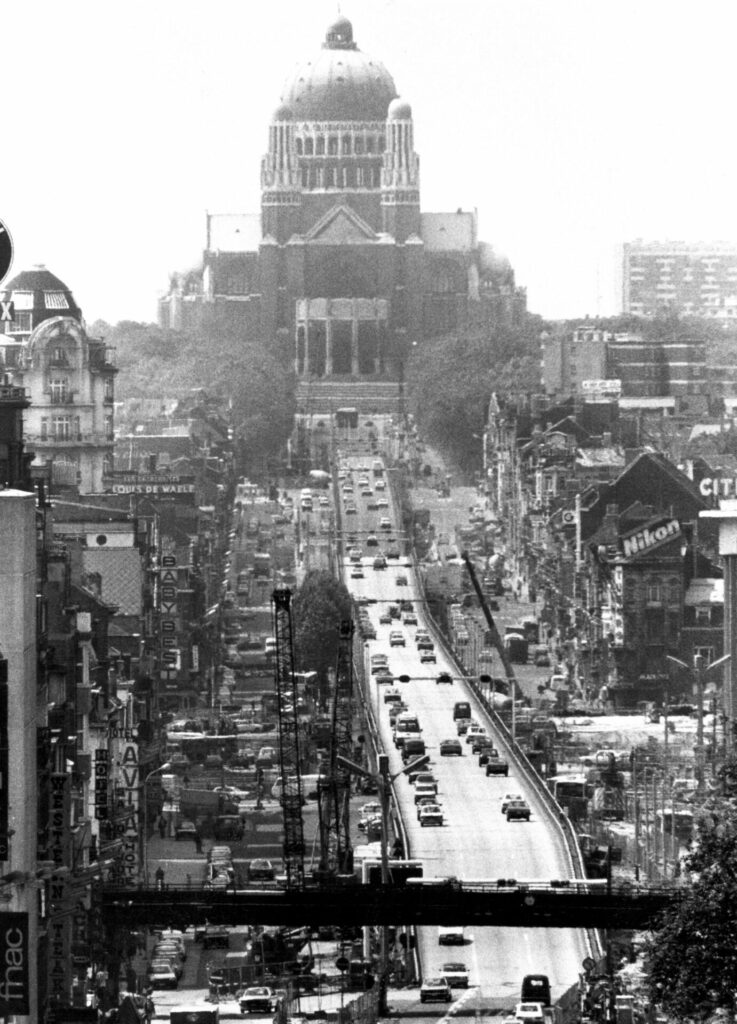

The Koekelberg Viaduct was the most radical element of the plan. The elevated three-lane highway ran above Avenue Leopold II, linking up with the second ring and the motorway to Ostend.

The viaduct that ran above Boulevard Leopold II

The country had never before seen a road engineering project on this scale. It allowed cars to sweep past the bedroom windows of elegant 19th century townhouses. The residents protested by hanging black flags over their windows during the Expo, but drivers were probably going far too fast to notice. One thing almost everyone agreed upon in 1958. The car was king.

More cars, bigger roads

The road network wasn’t just built for Expo 58. A mere ten percent of visitors were expected to travel to the exhibition by car. But the project was part of a much bigger plan to make Brussels one of the most car-friendly cities in Europe. The city issued a decree that required new office buildings to include one parking space per 50 square metres of office (the ordinance remained in force up to 2002).

Hondemarcq insisted his plan was essential for the vitality of the Belgian capital. He argued the private car was an essential factor of economic prosperity. It had to be promoted or the result would be “urban disorder and the decline in the city centre’s vitality.”

He went even further in defending his plan to transform Brussels. “Completing the works will give a shining demonstration of the fact that, far from destroying a city’s beauty, its modernisation will have conferred a more grandiose appearance in line with its dignity as a European capital,” he said.

The Leopold II viaduct, 1969.

And there was a prize to be won. Hondemarcq argued that by making Brussels the crossroads of Europe, by building all the fast roads, it could claim the coveted role of capital of Europe. He proposed this argument on September 28, 1957, just a few days after Belgium had submitted its official candidacy to host the seat of the European Commission and the Council of Ministers.

The highways, tunnels and viaducts were built to woo the first intake of European civil servants from Italy, the Netherlands, Germany, France and Luxemburg. And it worked like a dream. The European Commission was based (at least temporarily) in Brussels. It settled in the 1960s in the handsome Leopold Quarter where old 19th century town houses were torn down without any significant public protest. And the grand avenues – Rue de La Loi and Rue Belliard – were turned into urban highways to bring cars into the heart of the city and out to the E motorways that radiated across Europe.

The city went on to build several more viaducts in the 1970s to take traffic above the city streets. The Reyers Viaduct was built high above a residential street in Schaerbeek to carry traffic out to the E40 motorway. The Herrmann-Debroux Viaduct went up in 1973 to carry traffic above the streets of Ouderghem and out to the E411 motorway.

Copycat viaducts

The concept was adopted by other Belgian cities. In 1971, a noodbrug, or emergency bridge, was built in Antwerp to take traffic across the busy Frankrijklei boulevard. Intended as a temporary solution, it was still standing in 2005. The city of Ghent also built a concrete flyover to carry traffic right into the heart of the mediaeval city. Charleroi’s 6km ring road was mostly built as a series of viaducts.

Charleroi's elevated ring road

But Brussels remained the undisputed capital of the flyover. These bold, engineering projects transformed a rather sleepy European capital into a city when car drivers swept above urban streets at motorway speeds, then slotted their vehicles into convenient parking spaces below their office.

It’s hard to think of any other European city that has been so welcoming to cars. Rome has its elevated highways. London has the Westway. But you really have to look to American cities like New York or Chicago to see road engineering projects on the scale of Brussels.

Many local residents weren’t thrilled at the idea of an urban highway cutting through their neighbourhood. In the 1970s, campaigners in the leafy southern communes of Uccle, Watermael-Boitsfort and Auderghem successfully opposed a plan to drive the ring motorway through their communes, forcing traffic planners to come up with a different route, 15km to the south. The alternative route runs through the forest, far from residential neighbourhoods.

The original route of the ring can still be traced in southern Uccle where some areas earmarked for the motorway have been left untouched by development, including open fields and ancient woodland. But most of the proposed route has now been developed for housing.

The lack of a fast route in southern Brussels has meant that the Rue de Stalle leading out to the ring has some of the city’s worst congestion. Some groups including the Belgian Road Federation still argue for the ring road to be built along the original route. Only they now argue for a tunnel financed by tolls as the way to get this done.

Thai flyover

However public opinion in Brussels has turned against the flyovers. The Leopold II viaduct, like Antwerp’s noodbrug, was always meant to be a temporary solution, to be dismantled at the end of the World Fair. But it stood for more than a quarter of a century. Local wits referred to it as the “provisional, temporary definite viaduct”.

Built to carry 30,000 cars a day, the viaduct went on to carry more than twice that number. It was finally dismantled in 1984 when it was replaced by the Leopold II Tunnel (recently renamed the Annie Cordy Tunnel).

But that wasn’t the end of the Expo 58 viaduct. In the late 1980s, the Belgian ambassador to Thailand Baron Patrick Nothomb (father of the novelist Amélie Nothomb) came up with a proposal. The Belgian state would pay to ship the 2,000-tonne iron viaduct to Bangkok where it would be reconstructed to ease traffic congestion. The Belgian government saw the gift as a goodwill gesture that might lead to new trade deals (they didn’t happen).

The Leopold II viaduct in its current home in Bangkok where it is known as the Thai-Belgian Bridge

A Thai engineer was appointed to carry out the work. The bridge was built over a single weekend, 56 hours to be exact. The flyover is still standing in the heart of Bangkok as a symbol of Belgian-Thai friendship.

Tearing down Reyers

The Thai capital has gone on to construct a further eight flyovers to ease the city’s traffic problems. But back in Brussels, the viaducts are now being taken down, one by one. The shift can be traced back to 2015, when Brussels Region abandoned a plan to repair the crumbling 225-metre Reyers Viaduct and decided instead to tear it down.

The region had originally set aside €2 million to carry out repair work, but it turned out that the structure was seriously decayed, and renovation would cost at least twice that figure. Finally, Pascal Smet, the then state secretary for urbanism, announced a change of direction. “It belongs to the past,” he announced. “A new city boulevard will reconnect the districts on both sides of the boulevard and bring new life to the neighbourhood.” There would be more space for buses, pedestrians and bicycles, and less dedicated to cars.

Not everyone was happy with Smet’s plan. The Committee for the Reyers Viaduct action group launched a petition to save the viaduct. They argued it would cause problems for the 30,000 car drivers who used it every day, killing off small businesses and forcing companies to leave the city. But the plan went ahead, and on July 12, 2015, local residents held a party to celebrate the start of demolition work.

The Reyes Viaduct, before its demolition in 2015.

By the end of 2015, the concrete viaduct was gone. The handsome façades along the boulevard were revealed for the first time in 50 years. Locals immediately noticed more light in the neighbourhood.

The following year, a former director of road engineering revealed that the plans for the Brussels tunnels had been stored for many years in one of the concrete pillars holding up Reyers viaduct. Moreover, he thought the plans had probably been nibbled by mice.

It turned out to be a false rumour. The Region quickly came up with evidence to show the plans had been gradually removed from the viaduct pillar and carefully stored in a government building.

After tearing down the viaduct, the Brussels government took another eight years to agree a draft plan to create a “pleasant urban avenue” along Boulevard Reyers. In March 2023, the region announced its intention to set aside four lanes for cars, along with cycle lanes and broad pavements composed of high-quality material.

The Herrmann-Debroux Viaduct might be the next one to go. But not just yet. The viaduct currently carries 25,000 cars every day. Many of the drivers who use the viaduct are commuters from Wallonia who argue they need to use their car in the absence of any alternative transport.

The city had first raised the idea of demolishing the viaduct back in 2007. The decision was postponed until rail links improved. The government in 2015 repeated its plan to demolish the flyover and replace it with a green boulevard that would connect the city with the forest, but the project was again postponed.

The latest plan is to start pulling it down in 2025. But car drivers continue to protest, along with local residents who fear the work could drag on for 15 years.

And yet it seems Brussels has finally abandoned its ruthless focus on promoting car mobility. You can see projects all over the city that are creating cycle routes, open spaces and car-free streets. It looks like road viaducts are really a thing of the past.

But not in Flanders. Back in 2016, the action group ViaduKaduk organised a party in a park next to the E17 Viaduct that cuts through the Gentbrugge suburbs. The organisers insisted they were not a protest group seeking to tear down the 1960s concrete viaduct. They just wanted the government to come up with a creative solution to the problem of noise and fine-particle pollution.

The situation became more urgent in 2018 when pieces of rotten concrete fell from the E17 viaduct onto a bus passing below. The Ghent city architect called for the viaduct to be replaced by a tunnel. But the Flemish Region stuck to its original plan to repair the viaduct.

Vilvoorde repairs

There are no plans to demolish the massive concrete viaduct on the Brussels Ring that has towered over Vilvoorde since 1977. It was built to last 100 years.

But then something happened that sent a chill across Europe. On August 14, 2018, the Polcevera Viaduct in Genoa collapsed, sending cars plunging into the river below. It wasn’t long before Belgian newspapers were speculating about the safety of the country’s many concrete viaducts.

An illustration picture showing the viaduct of Vilvoorde, Brussels, Belgium after it's official opening on 29 December 1977

In August 2023, the Flemish government approved a plan to renovate the Vilvoorde viaduct. The flyover is made up of two bridges each measuring 1.7 km, resting on 22 rows of enormous pillars. The work involves relaying the asphalt, renovating the concrete structure, restoring the steel supports and replacing the guard rails. This colossal project will cost €500 million, according to transport minister Lydia Peeters, and take eight years to complete.

The Vilvoorde viaduct currently carries 150,000 vehicles a day. It is an essential part of the European motorway network that has to be fixed. But it is likely to cause massive traffic congestion for almost a decade.

The repair work might put to rest an urban legend that has been around for decades. According to industrial engineer Alex Bosmans, a construction worker was buried when he fell into one of the giant concrete pillars.

The car culture in Belgium – where the government still subsidises company cars – continues to have an impact on the quality of life in Brussels. While residents are turning away from cars, the city still has to deal with thousands of commuters every day. According to recent figures issued by TomTom satellite navigation, drivers in Brussels spend an average of 236 hours in their cars every year, including 91 hours stuck in traffic jams. Helpfully, TomTom points out that the time spent going nowhere amounts to reading approximately 47 books.

The traffic congestion is having a serious impact on Brussels’ ranking as a desirable city. In the most recent report on urban quality of life by human resources consultancy Mercer, Brussels dropped from 28th place to 36th, with traffic congestion cited as the main reason for the dramatic fall. It’s not the worst city to live in Europe, but it’s still a long way behind Vienna, Stockholm and Copenhagen.

Change the way you move, TomTom suggests. However, most people in Brussels – and Belgium – have still to get the message.