Ewa Abramiuk-Lété lives in Woluwe-Saint-Lambert, a commune where only a third of its residents are native-born Belgians. Town councillors, though, are almost all Belgian (an exception being a Finnish deputy director at the European Commission).

Abramiuk-Lété herself hails from Poland but has also become Belgian. She is now obliged to vote. Voting remains a civic duty for her despite the lack of real non-Belgian representation on the town council. "What should you do otherwise?" But she is also very positive about Woluwe-Saint-Lambert. "It's very clean, well-run, with lots of cultural events and the neighbourhood is lovely," she says.

With 450,000 non-Belgians and over 500,000 other citizens of non-Belgian origin, the de facto capital of Europe has become a massive testing ground for integration over the past 70 years. But why are we so reticent to vote, let alone stand, in local elections?

It's partly our fault for not ploughing through complicated town hall documentation in French or Dutch - or at least, that is the refrain heard for failing to register by the March 31 deadline to vote in Belgium at EU elections on June 9. Another early deadline looms on August 1 for the October 13 Belgian local elections. After 30 years of EU law demanding Belgium give Europeans the right to vote in municipal elections, the country's registration requirement effectively excludes over 80% of EU and non-EU foreigners from actually voting.

Are we too snobby to be interested in local politics, or just too lazy to fill out forms in Dutch or French or even go online? "Belgian politics really strike me as a private club,” says Adrian Hiel, an Irish Canadian with Dutch origins. “You need family connections to get into the club. So it's understandable and regrettable that we don't see many immigrants running for local office.”

Hiel joined Wezem'move, a new grouping of locals unhappy with how Wezembeek-Oppem is run. Around half of the commune's population is of non-Belgian origin, and 25% are real foreigners like Adrian, who has nonetheless called Belgium home since 2020. Located just outside Brussels, Wezembeek-Oppem town council, almost exclusively pure-bred Belgian, works in Dutch but provides documents and services also in French.

"There's a very small pool of interested, motivated, trilingual people with the time to take an active role in local politics," Hiel says, regretting the absence of non-Belgians on Wezem'move's emerging list for October elections.

Democratic deficit

Local Belgian party leaders don't help by drawing from a restricted pool of prominent candidates. Non-EU foreigners cannot stand as candidates. Placing an EU citizen in a prominent position on the list, or even a Belgian of foreign origin, may bring in fewer votes in communes with old Belgians still constituting a decent percentage of the population. And with only some 17% of non-Belgians registered for local elections, party leaders may be tempted to just symbolically place a few 'newcomers' in lower positions.

Migration researcher Thomas Huddleston from the University of Liège was heavily involved in a 2018 voter registration campaign in Brussels. He still feels a sense of urgency as actual numbers of eligible and registered voters decline in Brussels, potentially with half of Belgians and non-Belgians not or not being able to vote in October. “Brussels suffers from one of the greatest democratic deficits in the EU,” Huddleston says, calling for automatic voter registration and information for all newcomers.

Change is unlikely to come from the European Commission taking Belgium to court once again. The first time, led to a judgement by the European Court of Justice that forced Belgium in 1997 to grant EU citizens the right to vote and stand in municipal elections "under the same conditions as nationals". But despite dismal participation rates, EU officials are currently "not aware" of any practice employed by Belgian authorities that conflict with EU rules. Whether there is a change in the law by October 2030 is up to lawyers. It is likely too late for October 2024.

Figures from Ixelles show that, like the Brussels region as a whole, some 77% of the population is either non-Belgian or of non-Belgian origin (which could just mean they have a single non-Belgian parent). Some 23% of Ixelles residents come from another EU country and a full 14% from France. Some 14,000 other Ixelles residents acquired Belgian nationality at some point, like mayor Christos Doulkeridis did 35 years ago. "At the end of the day, residents, whether Belgian or not, expect the same things from the commune," Doulkeridis says.

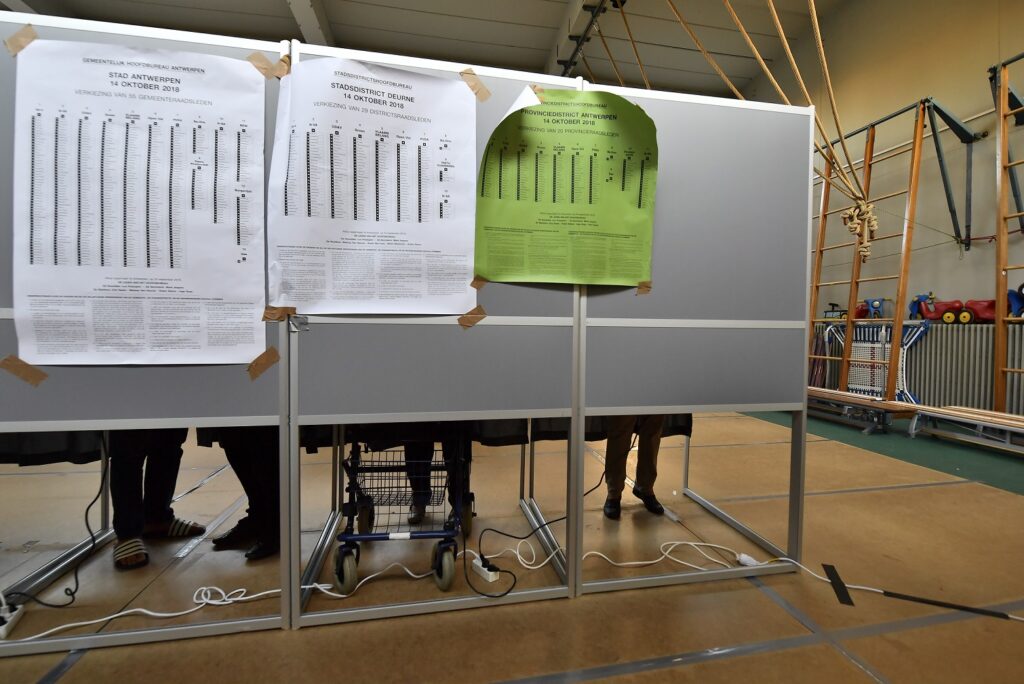

Illustration picture shows a polling station in Antwerp, Sunday 14 October 2018. Belgium votes in municipal, district and provincial elections.

BELGA PHOTO DIRK WAEM

"Registering to vote is a little complicated for some," Doulkeridis admits. But Ixelles is trying to make it as easy as possible, planning voter registration campaigns and even allowing foreigners to register to vote at the commune without an appointment. "I really hope we get better results in terms of participation at the town elections,” he says. Last time, Ixelles saw 27,000 of its potential EU voters, and 85% of its registered EU citizens failed to turn up at the voting booths on October 14, 2018.

Doulkeridis is all for automatic registration to treat Belgians and non-Belgians the same. But he does not want optional voting for municipal elections as in Flanders. "I don't agree with that. Voting is a right but also a duty. After all, it's not asking too much of people to go and vote every six years. This is what community is about," he says.

Monica Frassoni, the president of Ixelles town council, is not even Belgian. She was also the first ever non-Belgian to be elected as a Belgian MEP in 1999 on a French-speaking Ecolo party ticket. She was then re-elected in June 2004 as an Italian Green the first Italian elected abroad, before becoming co-chair of the European Green Party for a decade after 2009.

"It was a big surprise to be elected to Ixelles town council," Monica says. "I hadn't campaigned very hard.” Frassoni references the current Ixelles campaign to get out the vote among the commune's massive 77% non-Belgians: like mayor Doulkeridis, she wants automatic registration for local elections. "That would make things even easier," she says.

Democratic duty

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen grew up in her 'beautiful Tervuren'. And von der Leyen regularly takes breathers in the nearby forest and park. Today, the leafy commune, just 12km from the European Commission headquarters, boasts a full 43% of non-Belgians. But all town councillors are Flemish or French-speakers of Flemish origin. And Tervuren has also only registered 17% of its non-Belgians to vote.

"If you're not Belgian and don't speak the language and not sufficiently integrated, then politics is not really something for you," says Tervuren mayor Marc Charlier. "But it's everyone's moral duty to vote in a democracy, whether or not you're Belgian.”

Would voting not increase if candidate lists reflected the town's diversity? Charlier says parties already try to choose people from all parts of the commune, different ages and from different walks of life. "The Dutch, English and Germans are by far the largest. So it's normal that we try to get someone from those groups on our list,” he says.