Machetes, clubs, pickaxes and spears. These were the weapons used by Rwandans as they slaughtered their fellow countrymen during the 1994 genocide. They were used against colleagues, neighbours, friends, spouses, and in chilling instances, even their own children.

This year, Rwanda marks the 30th anniversary of the genocide, 100 days of unspeakable horrors that only ended on July 14, 1994. During those three months, between 800,000 and a million men, women and children perished – more than one-tenth of the population – mainly Tutsis killed by the majority Hutus.

Why did they turn against each other so savagely?

The genocide had many roots, some going back to centuries-old disputes. But one of them, often overlooked, is the role of Belgium.

Like Congo, its bigger neighbour, Rwanda was a Belgian colony, until 1962, the year of independence.

Rwanda had been a German colony since 1885, but the Belgians drove them out in 1916 during the First World War, and in 1924, the League of Nations officially gave Belgium a mandate over Ruanda-Urundi (a union of Rwanda and its southern neighbour, Burundi).

Unlike Congo, which is immense, boasting minerals, rubber, gold and uranium, Rwanda is resource-poor. “Rwanda was the backyard of the Belgian colonies. It was of no economic interest to Belgium,” says Léon Saur, a Belgian historian and associate researcher at the Institut des Mondes Africains in Paris,

Few in number, the Belgian administrators had to rely on the local elite, the Tutsis, to govern. Dabbling with anthropometry, the study of physical human dimensions, many Belgians and missionaries applied it to the classification and differentiation of races. They saw the Tutsis — who had finer facial features, were taller, sometimes up to two metres tall, and lighter-skinned than their Hutu counterparts — as a superior race.

The Hutus and Tutsis shared – and still share - the same culture, language, religion and traditions. Relations between them were relatively fluid, and intermarriage was common. But after the Belgians began favouring the Tutsis, their relationship with the Hutus would change. The Tutsis were, among other things, better schooled and trained by the Belgians, who needed educated personnel to run their administration.

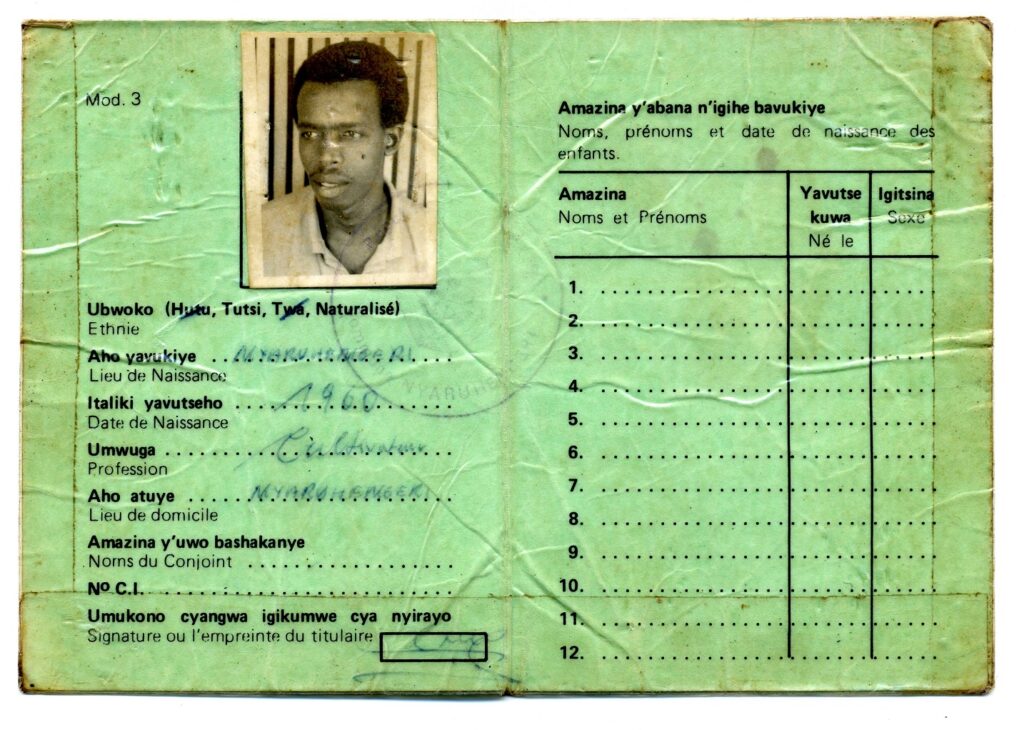

By 1930, the Belgian authorities introduced ethnicity on Rwandan identity papers. The concepts of Hutu and Tutsi, initially social categories, would become ‘races’, and Rwandan society would slowly become more ethnically split.

An identity card specifying the ethnic origin. Credit: Mémorial de la Shoah/coll. Kigali Memorial Center, Rwanda

The church also played a role as the evangelical White Fathers moved to covert Rwandans to Christianity. From the 1930s, it began opening its doors to the ‘little people’, mostly Hutus. While the Tutsis saw the church as an imposed element, for the Hutus, the church would be an instrument of emancipation.

Hutus, including their future leader, Grégoire Kayibanda, received education and training from seminarians and learned to speak Latin and French.

From social uprising to ethnic revolt

As a wave of independence movements swept across Africa in the 1950s, the main fear in Brussels was that Rwanda would fall to communists.

The Tutsi-led UNAR, the Rwandese National Union party, was pro-monarchist but the church and the Belgian authorities saw them as communists. Having previously favoured the Tutsis, the Belgians switched sides to support the Hutus.

Grégoire Kayibanda, the Hutu leader of the Parmehutu party, claimed the Tutsis were outsiders and therefore colonialists: he sought to abolish the privileges of the ‘Tutsi race’. The Belgians propelled him to power.

in his Pastoral Letter for Lent in 1959, Monsignor Perraudin, Vicar Apostolic of Rwanda, wrote: “In our Ruanda, social differences and inequalities are to a large extent linked to differences of race, in the sense that wealth on the one hand and political and even judicial power on the other, are in reality in considerable proportion in the hands of people of the same race.” Many saw this as a declaration of war against the Tutsis.

The shift in support meant the independence movement changed from a social uprising to an ethnic revolt. The revolution, which lasted between 1959 and 1961, saw the huts of the Tutsis burnt down and 300,000 flee to neighbouring countries.

Colonel Guy Logiest, then stationed in the Belgian Congo, was tasked with restoring order in Rwanda. He saw Kayibanda's Parmehutu as his solution: an openly Catholic party, and therefore “inevitably” anti-Communist.

With Belgium set to pull out of Rwanda in 1962, Kayibanda was confirmed as Rwanda’s first independent president (a 1961 referendum abolished the monarchy).

The internal conflicts would continue for decades with some episodes of violence against the Tutsis. But Brussels maintained healthy relations with Kigali and continued to send weapons to fight against the exiled Tutsis attempting to force their way back into Rwanda from neighbouring countries.

Peacekeepers flee

The genocide erupted more than three decades later, some four years into a civil war. On April 7, 1994, ten Belgian peacekeepers assigned to protect the Prime Minister were killed. The Belgian political world was stunned: nobody had expected it, especially since the Rwandan and Belgian militaries were intricately connected.

Then-Prime Minister Guy Verhofstadt in Kigali apologising for Belgium's role

The consequences were dramatic: Belgium withdrew its 450 soldiers from the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR), soon before being followed by other states, leaving the way clear for the massacre. Who knows how many lives might have been saved had they, and others, stayed?

On July 4, 1994, after 100 days, the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) created by exiled Tutsis seized control of the capital. Rwanda then entered a period of judging those responsible and, above all, of reconciliation. It was only this May that the UN war crimes tribunal for Rwanda wrapped up its mission, as it accounted for the last remaining indicted fugitives, two local organisers of Hutu militia, who were both charged with genocide and crimes against humanity.

As for Belgium, it was not until 2000 that then-Prime Minister Guy Verhofstadt apologised to Rwanda in a speech in Kigali: “In the name of my country, I bow before the victims of the genocide. In the name of my country, in the name of my people, I ask your forgiveness.”