Anarchism, regicide and Brussels. In April 1900, the Belgian capital was the scene of a high-profile (but now largely forgotten) assassination attempt on the British Prince of Wales at Brussels-North station. Driven by geopolitical grievances, the episode would mark the lowest point of Belgian-British relations.

On 4 April 1900, activists from the Socialist Advance Guard in Saint-Gilles had learned that Prince Edward – the future heir to the British throne and the eldest son of Queen Victoria – would be passing through Brussels by train on his way to Copenhagen the next day.

The Prince’s visit had caught the attention of the Saint-Gilles militants given that, at the time, Britain was waging a hugely unpopular war against the Boers in South Africa, a white settler-colonial population which spoke Afrikaans, a daughter language of Dutch (Boer means farmer in Dutch).

Many Belgians were infuriated by the reported atrocities in the war, particularly the concentration camps which had been set up for Boer prisoners. This was fuelling rampant anti-British sentiment across the country.

The attack

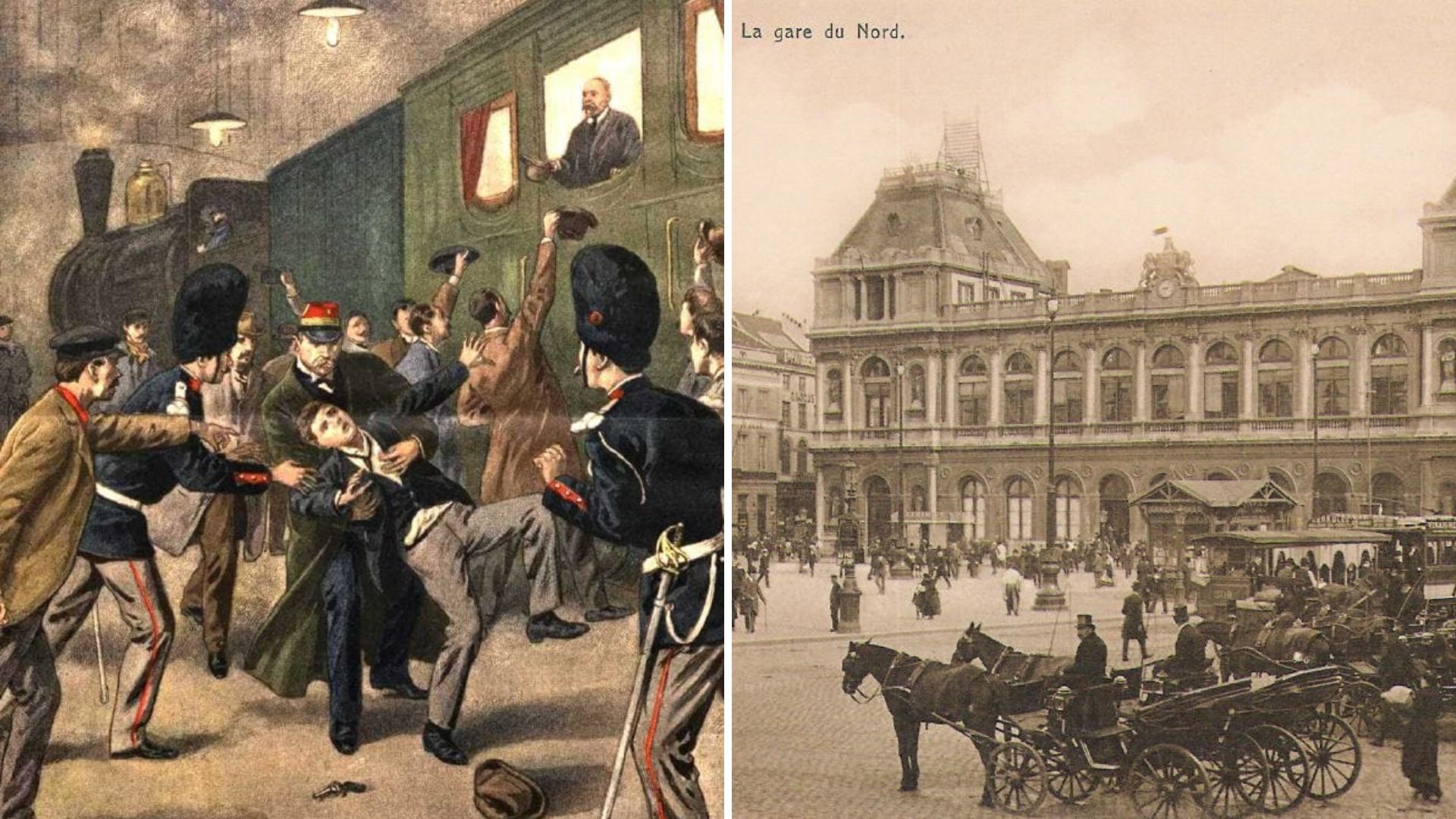

On the afternoon of 5 April 1900, Prince Edward's train had been stationed at the old Brussels-North station as it waited to depart onto its next stop of the journey.

Inside the royal carriage, the Prince and the Princess had reportedly been conversing about their upcoming meeting in Copenhagen. At 17:35 that warm spring evening, the train slowly began to pull away from the station.

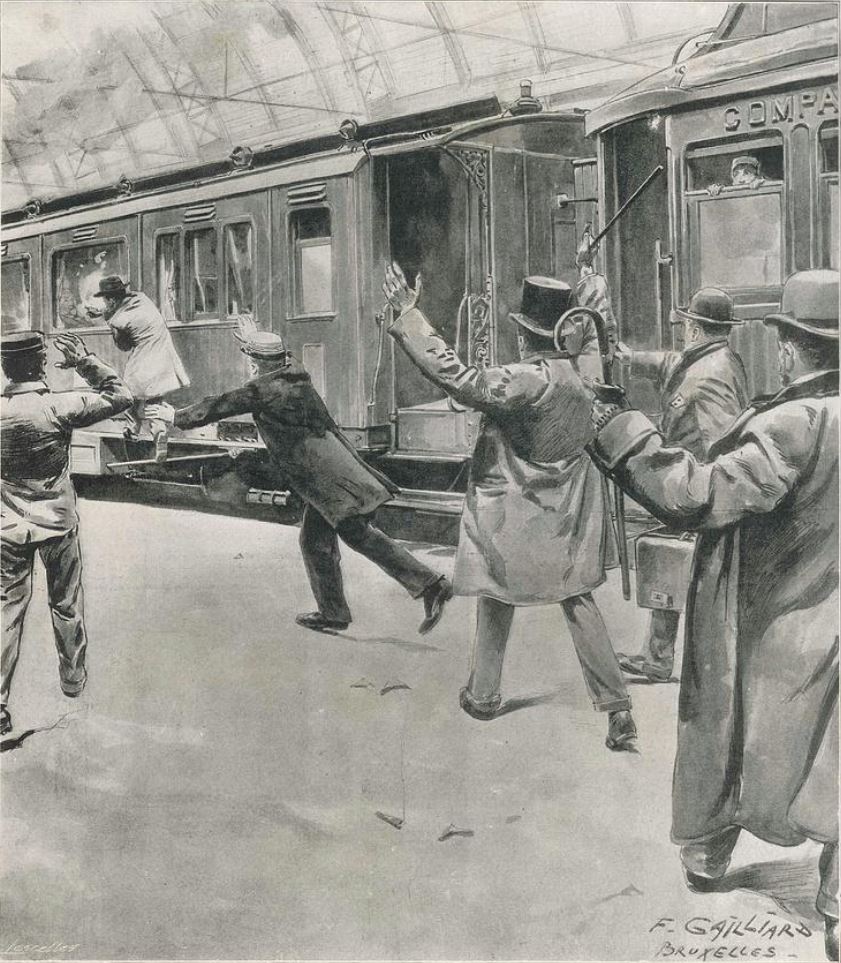

As the train began to gather pace, a 15-year-old boy with a round face and dark hair pushed through the crowd and jumped up onto the footboard of the compartment of the royal carriage. With a brisk movement, he pulled out a gun and fired two shots inside the carriage at the Prince.

One of the bullets cracked the glass of the train window, and the other hit the cushions next to the Prince. Both missed.

The attempted assassination of the Prince of Wales at Brussels-North Station on 5 April 1900 by Francois Gailliard

The British press jubilantly reported that the Prince had barely felt a thing. In fact, the Prince was so triumphant at his survival that he allegedly leaned out of the window to jeer "poor fool!" at the young Belgian anarchist. Edward later told the King of Denmark that one bullet had narrowly missed the side of his head.

Despite the assassination attempt, the royal train continued out of the station and onto its journey to Denmark.

Back on the platform, chaos ensued. In a matter of seconds, the boy was wrestled to the ground by the station master and was taken into custody for questioning by police.

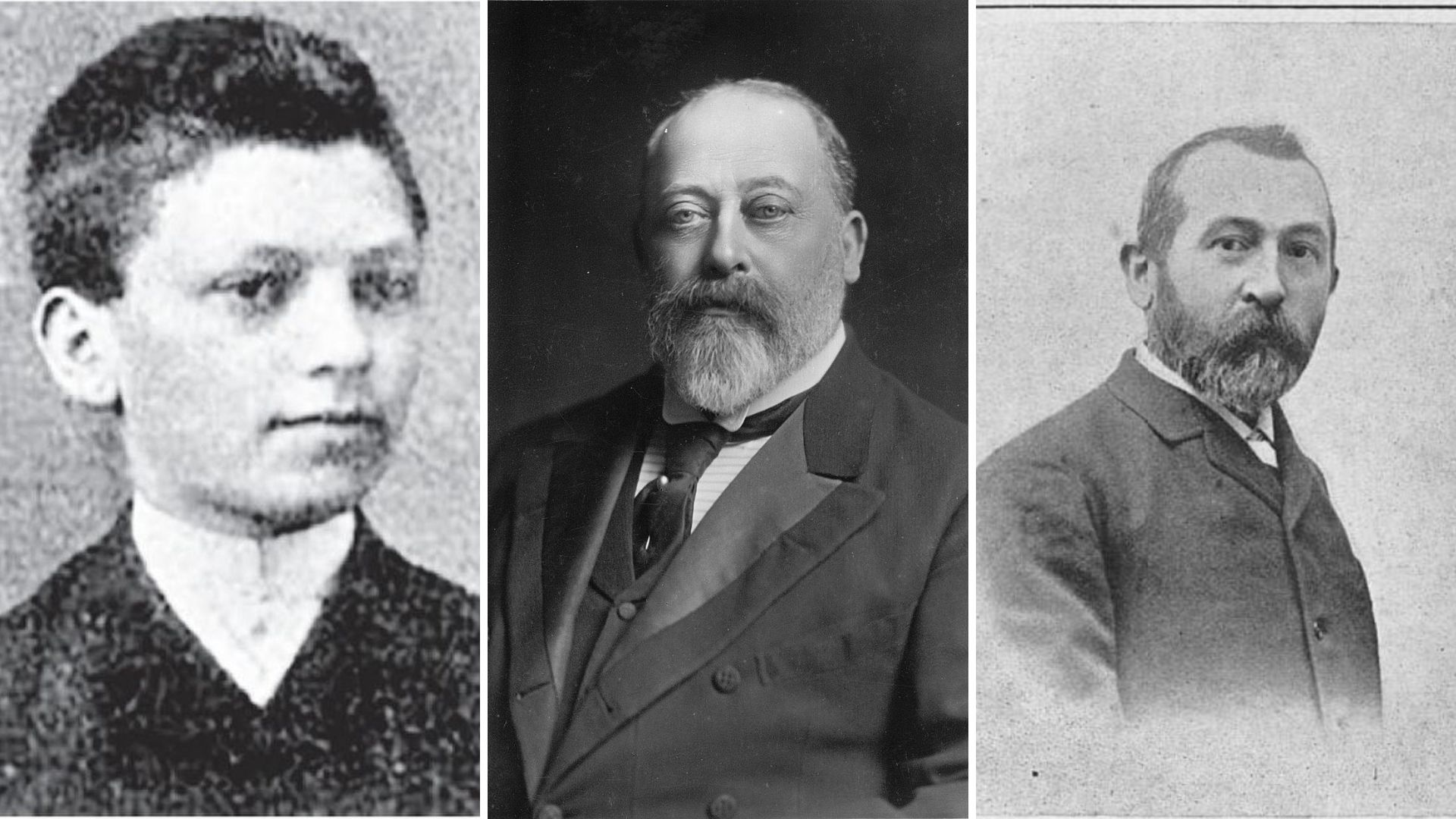

The boy was called Jean-Baptiste Sipido and was a young tinsmith's apprentice from Saint-Gilles, residing at Rue de la Forge. He was a member of the Socialist Action Guard (SAG), which was part of the group that had met the day before to discuss the attack.

Jean Baptiste Sipido (L); British Prince Edward (C) and Charles Crocious, the stationmaster (R).

In the immediate aftermath and during interrogations, Sipido showed no remorse for the attack – only that he had missed. He blamed the Prince for the murder of thousands of people in the ongoing Boer war in South Africa. This was the accusation that the boy had apparently shouted before firing his two shots into the carriage.

The police wanted to speak to the other members of the group in their search for accomplices. A few days later, the police detained other members of the Saint-Gilles wing of the SAG, and interrogated them about their motives.

Investigators wanted to confirm whether their organisation would pose a long-term threat. The Public Prosecutors’ Office requested the list of members from the leader of the SAG, Vincent Volkaert, who refused but was still called to testify in the trial.

The trial

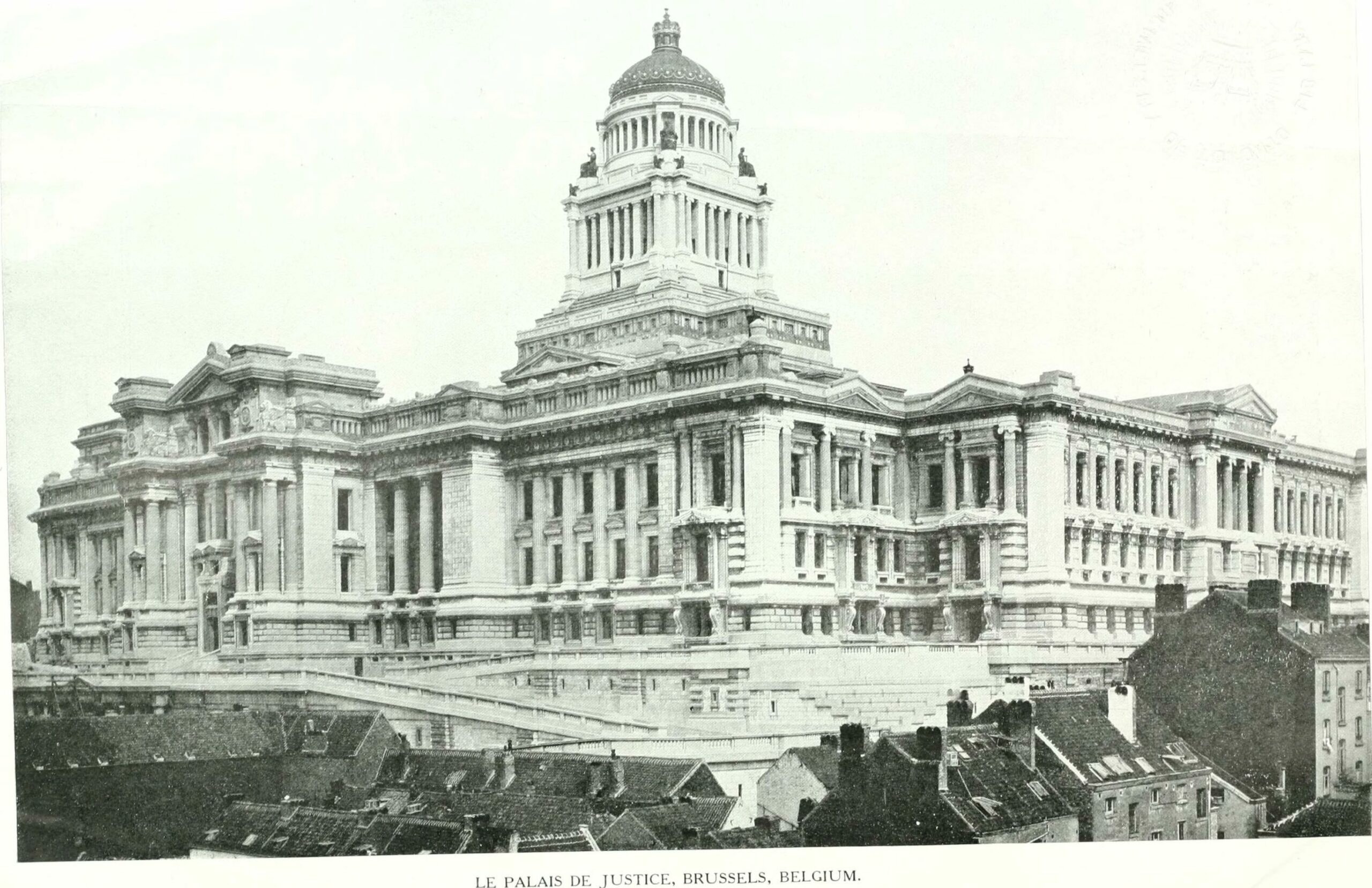

The trial was held two months later on 2 July 1900 at the Palais de Justice in Brussels. The case had sparked the interest of the international press, particularly given the scale of the indignation on the part of the British, but also the added interest of the link with a militant left-wing group.

Three of Sipido’s other friends (Arthur Meert, Julien Meire and Gaston Peuchot – all members of the same group) had been indicted alongside him. In the accounts of the day, it was noted that the Court President and the Public Prosecutor were dressed in bright scarlet robes, which were in sharp contrast to the sombre surroundings of the imposing courtroom.

The Palais de Justice circa 1910. Credit: Creative Commons

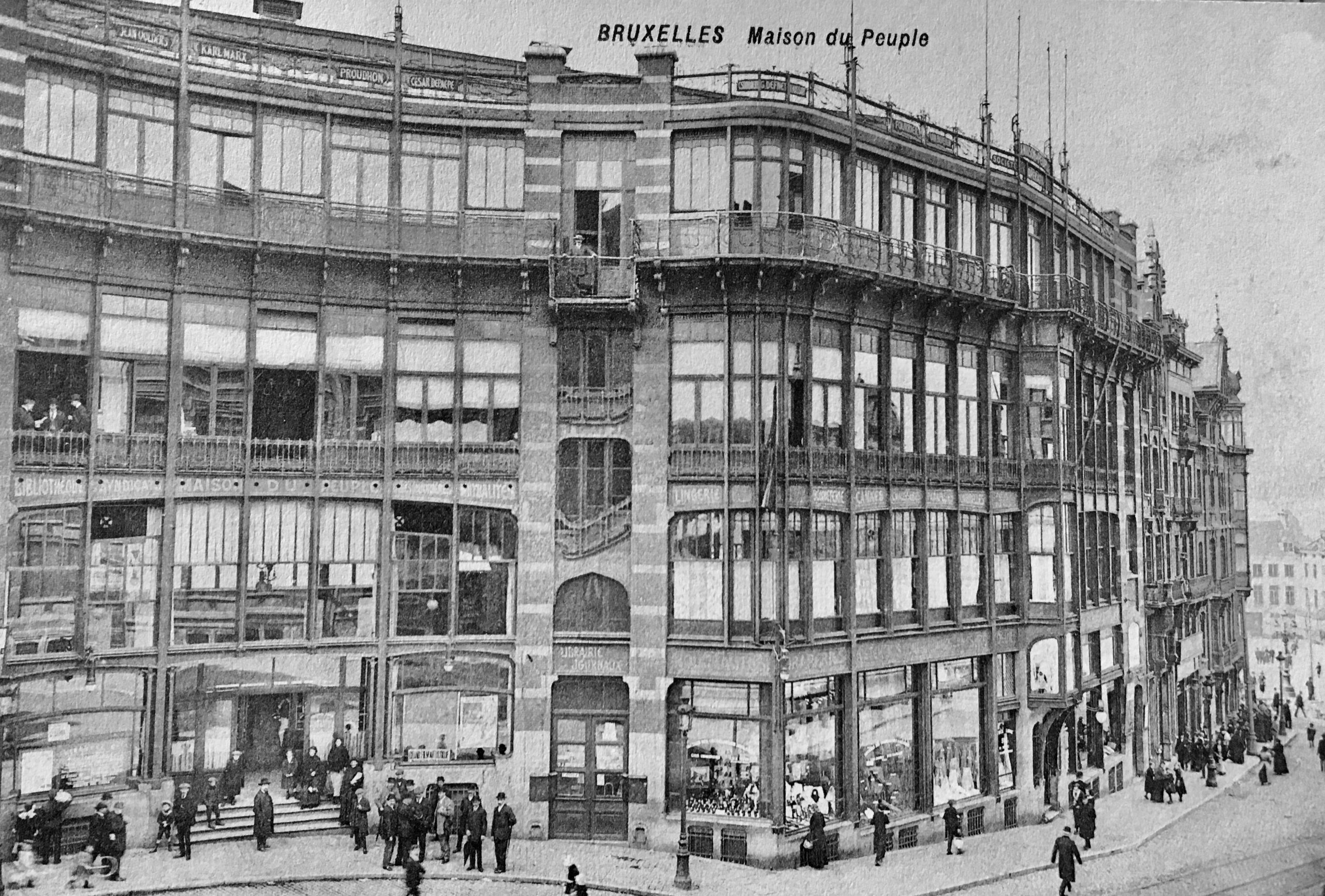

During the trial, there was much focus on the ideology of the socialist and anarchist militant group, particularly as it enjoyed considerable support across Belgium. It emerged that the four had met at the Maison du Peuple, the Victor Horta-designed working men’s club or cooperative, where worker movements were often organised to the dismay of the authorities.

Witnesses testified that they had overheard the activists in the Maison du Peuple saying: "if the Prince comes to Brussels, we should put a bullet in his head."

Wanting to prove themselves, Sipido and his teenage companions had put bets on who would actually have the courage to assassinate the British Prince. It also emerged that Sipido had been accompanied to buy a cheap revolver before making his way to the old Brussels-North station.

Sipido is described as having an open and intelligent expression throughout the trial, but also "having a more cunning eye when off-guard." The others are described as "repulsive" by the angry press. These were working-class boys, with jobs as a shoemaker, hat-maker and an errand boy.

The stationmaster, Charles Crocious, who had seized Sipido, had been rewarded by the British authorities with a scarf-pin decorated with the Prince’s motto "Ich Dien" as a thank you for his heroic actions. The British press lamented the fact that he did not wear them in court.

Maison du Peuple around 1900

As the trial went on, incriminating circumstances implicated Sipido's colleagues in the sale of a pistol, as well as showing him how to fire it. An inflammatory speech on the Boer war made at the Flemish Theatre in Brussels by the SAG leader Volkaert a few days before the attack was also cited as evidence of the group’s political motives.

In many press articles on the trial, the British press were more interested in ridiculing the political ideals of the working-class militants than the attempted murder of the heir to the throne itself.

Volkaert’s testimony was reported as having captivated the audience of the trial. Calmly and collectedly, the leader spoke with experience, denying all knowledge of the attack with "great oratorical effect", rebutting the arguments of the many who were trying to prove his guilt. The British daily The Sphere described him as the "philosopher, the guide and possible friend of these possible regicides."

The Verdict

Ahead of the judgement, the Public Prosecutor had irked the courtroom with a misjudged comment on the gratitude that Belgium "owed" England. This discontent was further exacerbated by the fierce attacks of prosecutors on the young teenagers – so fierce that they may have provoked sympathy for the accused.

Sipido and the other defendants decided to stay silent throughout the trial, their defence greatly resting on the testimony of Volkaert, but also Sipido's contacts, his age, and the fact that since his companions had also been arrested, he could not be held solely responsible.

The verdict came as a shock to all. The four young Belgian socialists were all acquitted on the grounds that they were too young to be held responsible – although Sipido was subject to five years' parole until he was 21. All four walked free that day – to the abject horror of the British press.

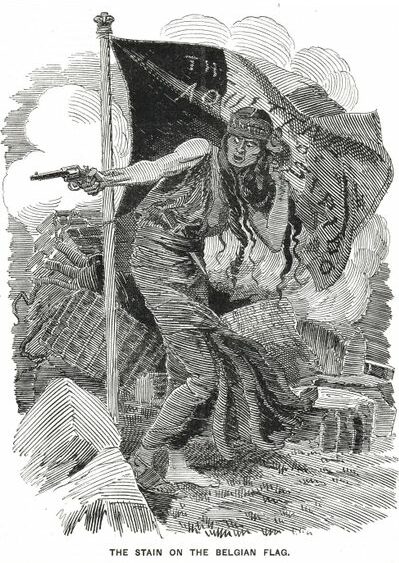

Cartoon about Sipido from British satire publication The Punch. The Belgian flag reads "The Acquittal of Sipido"

Furious British newspapers were convinced that Belgian sympathies towards the Boers had influenced the outcome of the trial, and the verdict was construed as a direct affront to Britain.

"The Maison du Peuple, the headquarters of the Socialists and the Anarchists of Brussels, will be rejoicing tonight," lamented the Globe on Friday 6 July 1900 after the verdict. "The cafe is a splendidly laid out and brilliantly lit building in the heart of the city, its main room is over 50 feet square, and here the workmen assemble every night."

The article continues, saying that the jury's refusal to "strengthen the hands of the Law in its endeavours to hold the more inflammable elements in check" would most certainly "bring danger to the community," with class dynamics also driving the story: "On all sides, the insult to England is recognised, and the verdict is condemned by the better-class Belgian wherever it is discussed tonight."

'The stain of Belgium'

In other newspapers, cartoons and caricatures of the young Saint-Gillois saw him wrapped in a Belgium flag, with the words "the Acquittal of Sipido" written across it and captioned "The Stain of Belgium". British Prime Minister Arthur Balfour called it a "serious and most unhappy judicial error."

After the verdict, Sipido escaped to Paris, with Leopold II vowing to his cousin Queen Victoria that he would do everything in his power to get the boy back – also partly because of Leopold's own nervousness about the atrocities being committed in his Congolese colony.

Indeed, in the following years, a British government report in 1904 would expose to the European and American press the conditions in the Congo Free State. These events further soured relations between the two.

But this bad blood between Britons and Belgians was not to last. Just 14 years later, when Belgium was invaded by the German Kaiser Wilhelm’s army in the Great War, Britain, led by Prince Edward's own son, George V would come to Belgium’s rescue, having guaranteed its security by treaty – with the fallout from the attempted regicide at Brussels-North station all seemingly forgotten.