Less than two years after the signing of the Armistice ending what was then known as the Great War, the strongest and fastest men and women of their generation gathered in Antwerp for an unprecedented festival of sport and culture.

One of the most remarkable episodes in Belgian history, the Antwerp Olympic Games of 1920 aimed to draw a line under the war that had so devastated the country.

But the Antwerp Olympics were also extraordinary because they were thrown together at breakneck speed. In April 1919, six months after the end of the conflict and just 12 months before the Games were set to begin, the International Olympic Committee named Antwerp as the host of the seventh Olympiad of the modern era.

While Belgium had been suggested as host nation as far back as 1912, the First World War interrupted the entire Olympic process (the 1916 Games in Berlin were understandably cancelled). Brussels was originally named, but before the war broke out, Royal Beerschot Football Club persuaded the authorities to switch to Antwerp, arguing that the proud city of Rubens was more suited to the Olympic culture.

But confirming Antwerp was a huge risk. Even then, Olympics took at least four years to prepare for, and that assumed the host country had not been ravaged by a war of unprecedented savagery and destruction. Ypres – or Ieper – the site of some of the bloodiest fighting just a few years earlier, had not been cleared of weapons or body parts. Indeed, many of the foreign athletes competing already knew Flanders, having served as soldiers for the Allied forces.

Another disruptive factor was the lingering 1918–1920 Spanish flu, which claimed between 25 and 50 million lives around the world, likely making it even more deadly than the Covid-19 pandemic.

The playing fields of Flanders

Heavily bombed during the First World War, Antwerp nonetheless responded to the challenge with vigour. The first stone of the transformed Beerschot Stadium, the oldest football field in Belgium, was laid by mayor Jan De Vos on July 4, 1919. The city tried to turn the war into an asset, with advertisements in sports magazines beckoning, “Come visit the battlefields of Liberated Belgium!"

A key political issue was whether to invite the defeated powers from the war. Baron de Coubertin, the founder of the modern Olympic movement, left the choice to the host country. But a demonstration by locals through the streets of Antwerp two months before the official opening indicated how strong feelings were against them. Germany, Austria, Bulgaria, Hungary and Turkey were not invited.

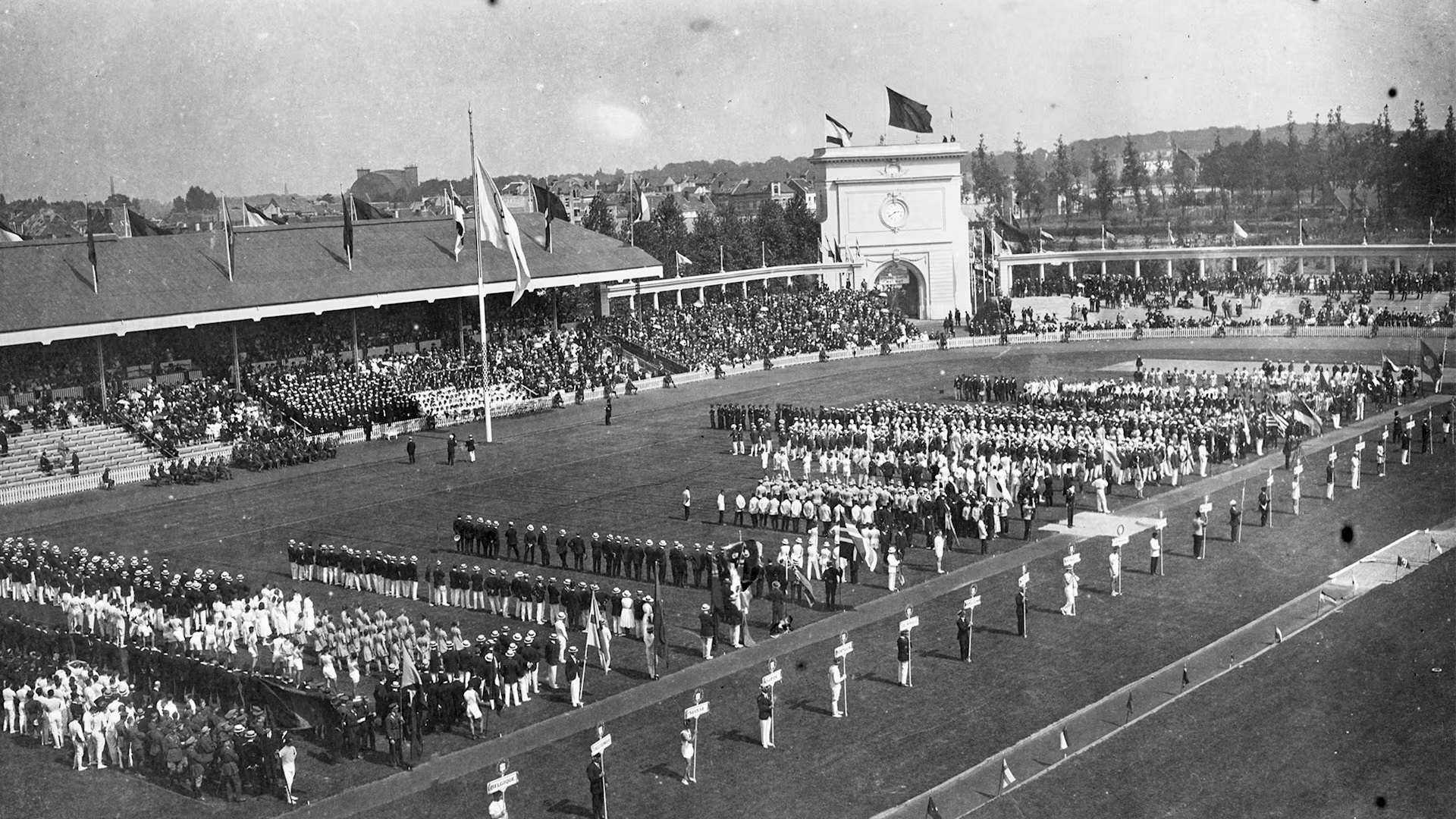

Record numbers still attended: there were 29 nations and 2,626 athletes competing in 154 events in 22 sports. Some were from newly created countries like Yugoslavia, Estonia, Czechoslovakia (succeeding Bohemia) and New Zealand (no longer part of a combined team with Australia).

Indeed, the echoes of war were felt throughout the games. At the opening ceremony, many of the athletes were soldiers and marched in uniform. The stadium itself had a plaster statue of a Belgian soldier heaving a grenade.

The games were officially opened on April 20 by King Albert and began with a Catholic mass, honouring athletes killed in the war.

There were many firsts at the opening ceremony. The first flight of white doves, symbolising peace and brotherhood, was released - ironically accompanied by the firing of a gun salute. The first Olympic oath was pronounced by former war Belgian pilot Victor Boin, a freestyle swimmer, water polo player and épée fencer. And Antwerp saw the first use of the Olympic flag, one of the most recognisable symbols in the world, with the distinctive five interlocking rings signifying the union of five continents.

Most of the events were held in the newly constructed stadium. But boxing and wrestling were staged in the zoology hall of Antwerp Zoo The swimming and diving competitions were held in the moat that surrounded the old city, with spectators on benches erected on ancient ramparts. Rowing was held at the end of the Willebroeck canal, amid reservoirs, oil storage cans and factories. Yachting was moved to Ostend, and shooting events were held at an army camp of Beverloo, 60km away – except for running deer shooting and trapshooting, which was near Antwerp.

Tug of war

The Games lasted almost five months, ending on September 12, as they combined both winter and summer events. There were some unexpected events on the programme, including polo, rugby, tug-of-war and korfball. Perhaps the most unusual of Olympic disciplines were the art competitions: medals were awarded in five categories – architecture, literature, music, painting and sculpture – for works inspired by sport-related themes.

Public indifference

The Belgian public was generally indifferent to the games. Some of the events, such as ice hockey and rugby, had never been seen before and were dismissed as exotic curiosities. Only swimming, boxing, wrestling and football drew big crowds.

US swimmer Ethelda Bleibtrey won gold in three women's contests and broke the world record in every one of her races

The women’s competitions faced particular prejudice. De Coubertin, obsessed with the male, chivalric ideal, was against women taking part and Count Henri Baillet Latour, Belgium’s chief Olympic figure, was a misogynist. Despite this, Antwerp can claim to have paved the way for the greater acceptance of women into the Olympics.

There were other problems. Rain left ruts and depressions on the track surface in the stadium, causing the runners constant worry – and it rained almost constantly during those August days of 1920.

The water for the swimming and diving events was dank, dark and, at just 10ºC, frigid: divers brought woollen stockings, socks and mufflers to keep warm and gave each other rubdowns between dives, while several water polo players were pulled out of the water on the verge of hypothermia

Red Devils world champs

In the final medal count, Belgium came fifth with 14 golds, 11 silvers and 11 bronzes (behind the US, Sweden, Great Britain and Finland). One of the lost important golds was that in football: the Belgians, already nicknamed the Red Devils, won the final after Czechoslovakia stormed off the pitch; in an era before the World Cup, could legitimately consider themselves world champions.

Belgium's winning penalty against Czechoslovakia to clinch the football gold

The football triumph was, unfortunately, one of the only upsides to the Olympics as far as the public was concerned. Antwerp lost money on the event – although it is by no means the only Olympic city to do so – as the organisers overestimated the economic benefits to the local economy and few considered intangible benefits like boosting local pride.

But if the games felt like an indulgence in 1920, they would come to be appreciated in time for helping relaunch the Olympics. To have athletes coming from all over the world only two years after the last shot was fired was an almost unbelievable feat of management

Baron de Coubertin was effusive in his gratitude. “Belgium has now succeeded in setting a record of intelligent and rapid organisation or – if I am allowed to speak in less academic but more expressive terms – a new record for its skill in improvisation.”

The stars of Antwerp

The Antwerp Olympics - which included both summer and winter events - showcased a new generation of athletes. Here are some of the sporting highlights:

- Finnish middle-distance runner Paavo Nurmi won the first three of his total of Olympic gold medals. The ‘Flying Finn’, whose statue stands outside the Olympic stadium in Helsinki, was forced to quit school at the age of 12 and work as an errand runner. Fellow Finn Joonas ‘Jonni’ Myyrä shattered the javelin record by more than five metres with his 65.78m throw.

- France’s Joseph Guillemot, a pack-of-cigarettes-a-day man and wartime victim of poison gas attacks, won the 5,000m title. He nearly repeated his feat in the 10,000m but suffered from stomach cramps and shoes that were two sizes too big after his own were stolen. He still managed to win silver.

- The Canadian side that won the ice hockey gold was made up entirely of players of the Winnipeg Falcons. Even more remarkably, all but one of them were Icelandic immigrants, who had cut their teeth playing against each other as none of the other Winnipeg teams wanted to play a squad consisting of "ragtag immigrants."

- South America claimed its first gold medal in 1920 when Guilherme Paraense of Brazil won the rapid-fire pistol event.

- French ace Suzanne Lenglen, the first real global tennis star, won the Olympic singles gold, losing only four games along the way.

- Italian fencer Nedo Nadi won the individual foil and sabre titles and led the Italians to victory in all three team events, for a record of five fencing gold medals.

- American diver Aileen Riggin, from Newport, Rhode Island, became the youngest gold medal winner at just 14 years and 119 days. At 1.40m tall and weighing 29.5kg, she was also the smallest athlete at the 1920 Olympics.

- At the other end of the scale, 72-year-old Swedish shooter Oscar Swahn won silver in the team double-shot running deer event to become the oldest medallist ever.

- American Eddie Eagan is the only athlete to win gold medals during the summer and winter Olympic disciplines. He won the light-heavyweight boxing title in Antwerp and in 1932 at Lake Placid, he was part of winning bobsleigh team.

- Jack Brendan Kelly, a 20-year-old manual worker from Philadelphia, won two rowing titles in the space of just 30 minutes. His daughter, Grace Kelly, would later become a Hollywood star and Princess of Monaco.

- US swimmer Ethelda Bleibtrey won gold medals in all three women's contests –100m and 300m freestyle and the 4x100m relay – and broke the world record in every one of her five races.

- Ukelele-strumming, Hawaiian surfing pioneer Duke Kahanamoku won golds in the 100m freestyle and the relay, while also representing the US in water polo.

- Britain’s 1500m silver medallist Philip Noel-Baker would later become an MP and nuclear disarmament activist. In 1959 he became the only Olympian ever awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.