People dressed as caricatures of orthodox Jews participated in the annual festival in the Flemish city of Aalst in February. Exactly the same happened the year before, closely watched by international and local media. Was it an expression of antisemitism, just bad taste, or an innocent display of humour in a long tradition of festivals?

To explore the background to what happened, we would need to examine the very roots of carnivals in Belgium, through the centuries, and look at how they have been interpreted by historians. There were times when the carnivals were forbidden. Making fun of minorities, using stereotypes of them, seems to be a distortion of the original idea behind carnivals.

From Paganism to Christianity

It started as a popular street feast with origins in Germanic and Roman traditions. The early Christians allowed hedonic feasts right before the start of fasting. One definition describes the carnival as “an annual festival, typically during the week before Lent in Roman Catholic countries, involving processions, music, dancing, and the use of masquerade.”

The sources of this feast are clouded in mystery. It could have some of its earliest origins in Roman feasts, like the well-known Bacchanalia and Saturnalia. The first one honoured the god Bacchus, while the second tried to appease Saturn, the god of agriculture. Roman society believed in fertility rituals. The Germanic tribes also tried to appease their gods.

Since the Middle Ages, there have been strong traditions of “rituals of reversals”, where men dressed like women or even “fish in the sky” were seen. Due to its popular character, the social elites tried to distance themselves from the feast and organised their own carnival balls, for example the highly commercial Venetian balls.

Indeed, the carnival tradition seems to have started in the Italian peninsula. The word carnaval has long been interpreted as stemming from either carne vale, saying ‘goodbye to meat’ or even carrus navalis, a ‘ship cart’. However, the earliest written source, in a document from 965 attributed to Subiaco, a Roman monk, refers to the feast as carnelevare.

During the Middle Ages, popular theatre also took place during the carnival festivities and made use of people in disguise and low-brow humour. Processions – in a parody of religious processions – crawled through the narrow medieval streets. The end of the carnival was concluded with the burning of a straw manikin resembling Prince Carnival, who had symbolically ‘ruled’ the city in a ‘mad’ way.

From the 15th century on, carnivals were organized by the city councils themselves. When the jester figure was introduced, their clownish behaviour added even more colour to the popular feast. Those in power did not always appreciate the carnivals and banned them in the 16th century. They were authorised again in the 17th century, mainly for commercial reasons, only to disappear in the following century.

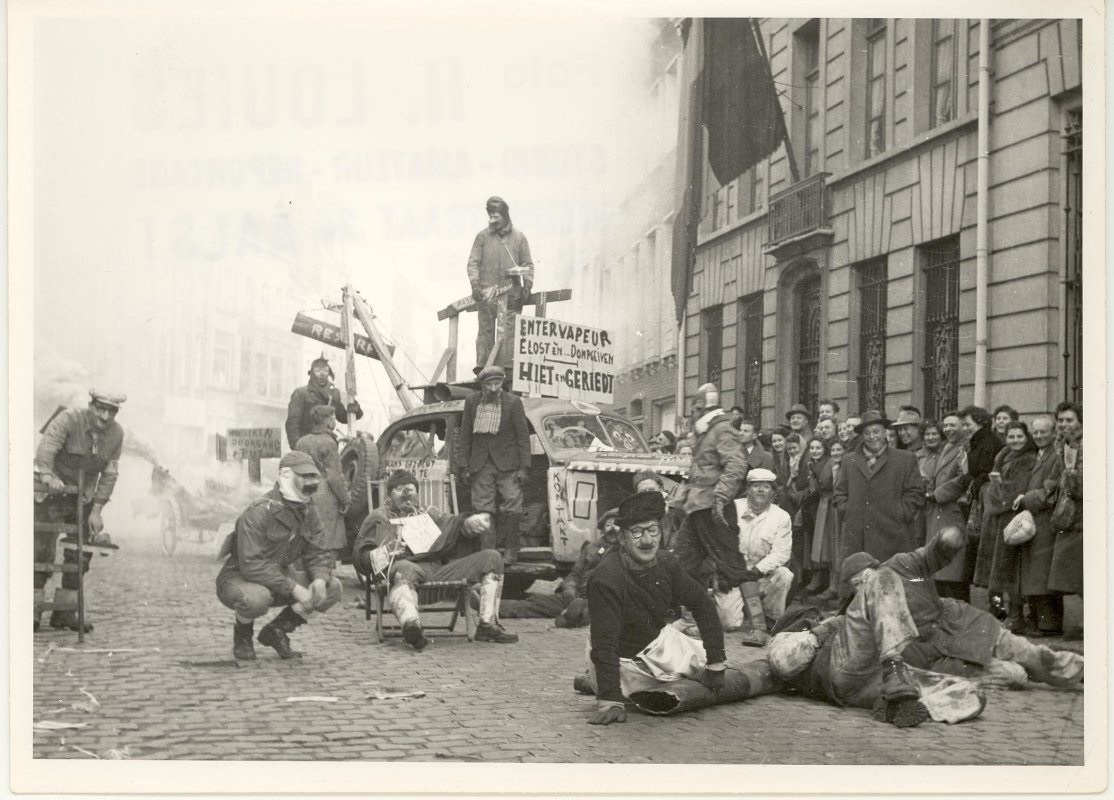

Aalst Carnival in 1935

The carnivals in the Middle Ages gave rise to strange habits, where people were not shy about showing cruel behaviour to animals. Today, that behaviour has left its traces in the tradition of visjesdrinken during the ‘Krakelingenfeast’ in Geeraardsbergen (Flanders). This ritual drinking of tiny live fish in wine from a silver chalice, by the aldermen or councillors of the cities, continues to be criticized by animal welfare organisations.

Another example is the ‘Kattenworp’ in Ypres, where the city’s jester threw living cats down the belfry tower until 1817. Luckily for the cats, they were replaced in 1938 by toys.

| Listing and delisting by UNESCO In 2010, UNESCO added both the ‘Krakelingenfeest’ and the Carnival of Aalst to its Representative List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. But Aalst went too far according to UNESCO. “The satirical spirit of the Aalst Carnival and freedom of expression cannot serve as a screen for manifestations of hatred,” said Ernesto Ottone Ramirez, Assistant UNESCO Director-General for Culture, in 2019. “These indecent caricatures go against the values of respect and dignity embodied by UNESCO and are counter to the principles that underpin the intangible heritage of humanity.” Because of the criticism in 2019, the City Council of Aalst decided to withdraw the carnival from the UNESCO List before being delisted. This leaves the ‘Krakelingenfeest’ and the Carnival of Binche (Wallonia), with its strong aesthetic element in the form of ‘Gilles’ costumes, as the only Belgian carnival left on the UNESCO List. By their rhythmic rattling, the Gilles scare away evil spirits according to old traditions. |

Historical interpretations

Historian Hans Moser explained that the carnival was introduced by the Catholic Church for didactic and liturgical purposes. The idea was based on the two-state model of Saint Augustine, contrasting civitas terrena, the earthly city to civitas caelestis, the heavenly city. Another historian, Werner Metzger, interpreted the carnival as a ritual calendar feast with roots in the economic reality of peasant life.

American historian Edward Muir famously wrote that the carnival was a city ritual for mediation and channelling frustrations. Indeed, carnivals have been organised since 1450 by the cities, and included processions of carts on wheels in the form of ships. A kind of reversal of the world took place, as can be seen in the chaotic paintings of Hieronymus Bosch.

Dutch historian Herman Pleij wrote about carnivals as being a feast of youngsters. In the late medieval city, it was the only period during the year when the young generation could display subversive behaviour that was forbidden during the rest of the year. Society’s only accepted order was one of hard work, frugality and staying within the rigid class boundaries.

For Russian philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin, the grotesque body is celebrated during the carnival. The boundaries of the physical body are expanded. In this sense, carnivals are part of a popular underground culture. Proof of this is clearly found in the carnival traditions in Aalst, which has been officially organised by the city council since 1923.

Aalst Carnival in the 1950s

Asked by The Brussels Times to comment on the controversial carnival floats, Herman Van Goethem, rector of Antwerp University, curator and first director of the Museum of the Holocaust and Human Rights in Mechelen, said that the entire Jewish community, “the Jew”, was targeted and ethnically framed and displayed as caricatures, with racist physical and behavioural features. “This is reprehensible, repugnant and unacceptable.”

So, what then is the answer to the question in the introduction? Is the Aalst carnival a display of humour in a long tradition of festivals or did it deteriorate to bad taste or, even worse, antisemitism in recent years?

From innocent caricature

The Brussels Times spoke to cartoonist Bram De Baere, the very man who drew a seemingly innocent caricature for the carnival in 2018. His caricature was later used by a carnival group the following year in the way that drew strong criticism and eventually led to the delisting of the Aalst carnival by UNESCO.

Bram De Baere, born and raised in Leuven and with grandparents from Aalst, feels deeply attached to the carnival tradition there and wants to put things in a proper perspective. The number of officially registered groups exposing carnival floats in Aalst ranges between 70 and 80, he says.

According to Bram, the elaborate floats poke fun at political figures from near and far, including American President Trump, North Korean Leader Kim Yong-un, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, Belgian Health Minister Maggie De Block, and local politicians in Aalst.

He does not think that the Vismooil’n (Fish Faces), the carnival group, which targeted Orthodox Jews, stood out in the carnivals in 2019 and 2020. “A little original or funny, rather modest in size and quality of execution,” he comments.

Bram adds that afterwards, their floats were portrayed in the media as “the defining image” of the Aalst Carnival. Out of context, he can certainly understand why some see offensive stereotypes. But the “intention was certainly much more innocent than that,” he says.

De Baere tries to reconstruct what happened. This particular carnival group was “going to take it easy this year, not spend too much money and recycle a number of things.” One thing led to another. “We are taking a Sabbatical year,” the group said and for that reason decided to “do something about Jews”. So, they decided to use a figure from the previous year.

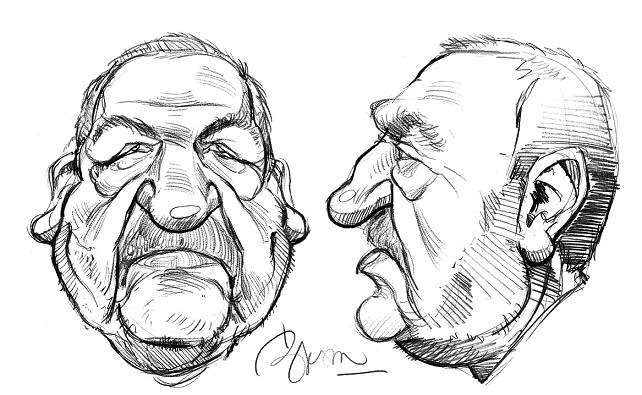

The figure that the group used was a caricature drawn by Bram of Michel Van Brempt, a local right-wing politician, who was portrayed as a Catholic crusader in the 2018 carnival. His figure was recycled in 2019, now to portray orthodox Jews surrounded by moneybags. It evokes antisemitic stereotypes, but Bram does not believe that this was the intention.

Caricature drawing of Michel Van Brempt, a local right-wing politician.

“Context is everything,” he says and refers to the tradition of reversal ritual that makes the Aalst carnival unique. “One day a year, you could go to your factory boss and laugh at him, even at the priests... In short, people were laughing at anything or anyone of power, influence or prestige in daily life. The authorities accepted and embraced the ‘honour’ to be mocked.”

“An outsider would not understand this and would only see bad taste.” It is also in this context that the ‘Voil Jeanet’ (meaning ‘Dirty Gay’, for wearing women’s clothes) originated. The poor workers had no money for a suit or a special disguise. They only had old clothes they borrowed from their wife or mother and some attributes they found in the house. This even resulted in wearing a lampshade on the head.

To antisemitic stereotype

Bram admits that the carnival in Aalst still has a ‘dirty edge’. “People laugh at things that you are not supposed to laugh at and react to suffering, disasters and scandals of the past year,” he explains. “Putting people in their shirts is more important than splendor. The Aalstenaar can clean his sleeve for three days and ridicule everything that disturbs him. When UNESCO decided that you aren’t allowed to laugh at X or Y, you hit the carnival at its very core.”

“As a cartoonist, I think that it’s definitely worth protecting the right to mock everything.” That said, he understands that the Jewish community found the use of his original caricature “absolutely shocking,” but assures that it had nothing to do with antisemitism among the organisers of the carnival.

After the controversial 2019 edition of the Aalst carnival, the event was stripped from its UNESCO status as “Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity”.

The mayor of Aalst, lawyer Christophe D’Haese from New Flemish Alliance (N-VA), was less successful in his contacts with the media and did not respond to questions from The Brussels Times.

The party leader Bart De Wever, himself a historian and mayor of Antwerp, has criticized D’Haese for being insensitive to the Jewish community but stopped short of expelling him from the party.

“These representations are caricatures that recall the worst period in our collective memory,” De Wever noted. “Resorting to such representations at a time when antisemitism is on the rise is regrettable. Even if the intention was certainly not antisemitic, it’s a pity people do not realize there’s a target for every message.”

Andre Gantman is a Jewish councillor in Antwerp and member of the same political party as D’Haese. He does not find it “funny” to make use of antisemitic stereotypes and laugh at orthodox Jews 75 years after the Holocaust. How does he explain that there were no protests in Aalst, a town of 85,000 inhabitants, against the carnival for “making fun” of orthodox Jews?

“Apparently no-one in Aalst expressed any protest, everyone seemed to support the carnival as it is,” he replied. “I didn’t notice any negative reaction from the political class as a whole in Aalst. On the contrary, criticism was dismissed as censorship. The carnival is seen par excellence as being against censorship and the lack of democracy in society.”

“People apparently don’t understand that, although they don’t consider themselves as antisemites, they are inciting antisemitism. They put the anti-Jewish ‘fun’ on the same level as the one they use against the church and the political establishment. In these circumstances, dialogue is very difficult,” Gantman concludes.

| Laughter in a historical perspective Laughs best laughs last. The last word is given to Johan Verberckmoes. The Brussels Times asked him about his opinion on mockery in the carnivals. Verberckmoes is professor of Early Modern Cultural History at KU Leuven and has written a PhD on laughter in the Spanish Netherlands. His research interests are the history of emotions, laughter, humour, pleasure, and the history of cultural exchange in the early modern world. Is there a special form of humour in Belgium in general and Flanders in particular and if so, how would you describe it? From research, we know that there is a certain sense of humour in every country, and that people like to laugh at themselves and others. This is of course also the case in Belgium, and maybe one can add that we have a kind of “surrealistic” humour. Flemish humour has also to do with how we use language, e.g. in comparison with our Dutch neighbours. Does it also have something to do with the fact that for centuries, Belgium was ruled by the Habsburg dynasty and laughter at foreign governments was a way of coping with the situation? Not really, because the Habsburgs were largely seen as the rightful rulers. There was no need of humour as a safety valve to express dissatisfaction with their rule and to make fun of them. Is making fun of vulnerable or persecuted groups in society a deviation from the original carnival idea or at odds with society's values today? It’s a common conception that you could laugh at everything during the carnivals, but this is simply not true. Everything must be put into context. There is always a risk that your humour isn’t accepted because it hurts someone. It makes me think of historical examples. This actually happened in Nuremberg, Germany, in the 1530s when the Schembardlauf carnival, organised by the guild of butchers, mocked a protestant preacher. The authorities didn’t accept this, and after having taken place for almost 100 years, the carnival disappeared, until it was revived in 1974. During the centuries there were often restrictions. It’s a myth that it was allowed to laugh at everyone and everything. If a carnival is supposed to be an inclusive event, and the town in which it takes place isn’t an isolated island, then things can go wrong if you laugh at fellow-citizens. Is it credible that the organisers of the carnival in Aalst weren't aware that their use of caricatures of orthodox Jews with moneybags is the same as in antisemitic propaganda? Unfortunately, antisemitic prejudices have existed in Belgium and haven’t disappeared yet. I can accept that those behind the floats didn’t have any intention to spread antisemitism, but it shows a lack of historical awareness. |

By Tom Vanderstappen