As with everything in Belgium, the country's university life can seem a little strange to people who are not used to its peculiarities. So with just a few more weeks to go before the academic year for higher education starts, here is an overview of what's most important.

From finding a 'kot' and going back home every weekend to six-week modules and student hazings, The Brussels Times gives an overview of what life at universities and colleges in Belgium is like.

What does the academic year look like?

Unlike primary and secondary schools, classes in higher education in Belgium do not start around the first of September (Flanders) or the last week of August (French-speaking education), but only from the third week of September.

While the academic year is structured around a certain logic, not all universities follow the saw calendar. Broadly speaking, there are two ways to divide the year: in semesters or by modules.

- The semester system

Nearly all universities and most colleges use the semester system, where the year is split up into two semesters of 13 teaching weeks. At the end of each semester, there is an examination period.

The first semester runs from late September until the end of December or January. As the exam period falls in January, immediately after the Christmas holidays, most students use those two weeks of "holiday" as an intense study period. The January exams are followed by a lecture-free week, which also signifies the end of the first semester.

The second semester starts in February and runs until early-mid June. Since there is no or only a very short study period before the June exam period, many students use the two weeks of the Easter holidays as an opportunity to already start studying.

For students who passed all their exams (including those in January), a blissfully long summer holiday awaits. Those who failed certain subjects have resits at the end of August/start of September, meaning that (parts of) the summer holidays are used to study as well.

- The module system

This module is used more often in colleges (which focus more on practical experience and applying the materials) than in universities, but only a minority of schools offer this system.

These modules divide the year into four blocks of six teaching weeks. This means there are also four major evaluation periods. After the teaching weeks, students have one week to prepare before a period of one to three weeks for exams. This happens four times a year, with the exam period falling around early November, mid-January, late March and mid-June.

While this means students have to study for exams more often, some prefer it over the semester system because it means there is less material to study per exam period.

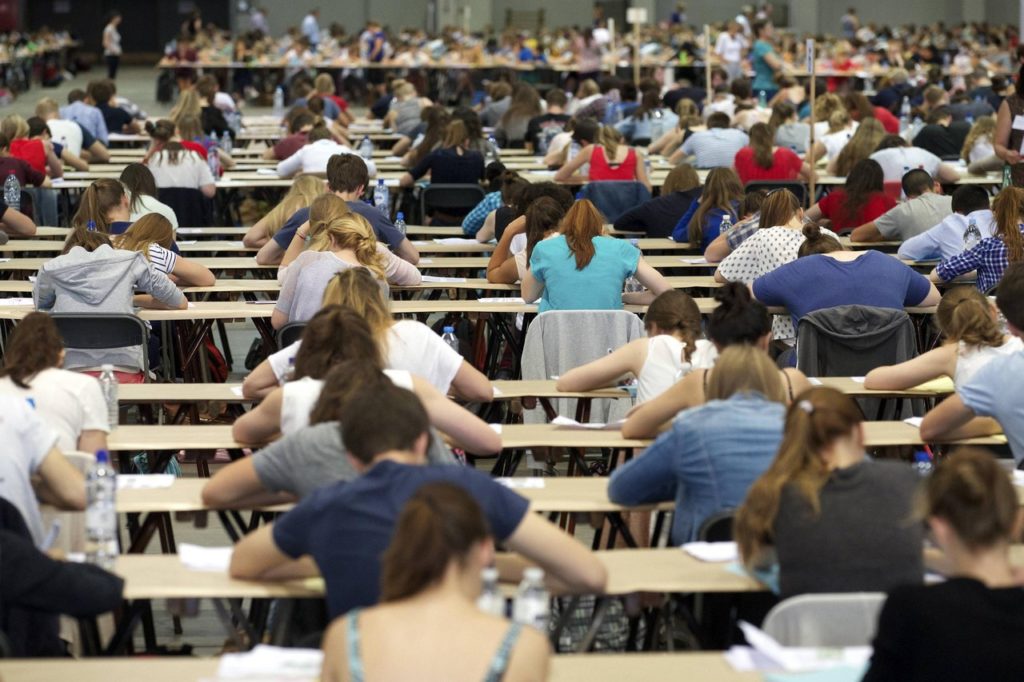

Students during university exams. Credit: Belga

The module system follows the holiday system of primary and secondary schools a bit more closely: students usually have all the regular holiday periods: autumn break, Christmas, spring break and Easter.

Still, many students use these lecture-free periods to catch up on missed lessons, do group works, write papers, prepare presentations and/or start studying for the upcoming exams (which are never far away in a six-week module).

What is a student 'kot' and how does it work?

Depending on how far a student lives from their preferred university, they can opt to move into a student room ('kot' in Dutch, 'kot étudiant' in French). Those who live close by often choose to stay at home and commute to class every day.

When looking for a kot, students can rent on the private market (a room or small studio in a bigger building full of student rooms) or through the university (in a large student residence). The latter option is usually cheaper and also gives priority to students whose families are struggling financially.

A university student residence is usually quite large, and the rooms already contain furniture (a bed, a wardrobe, a desk and a chair). Per floor, there are shared areas, such as the kitchen, showers and toilets and a recreation room. Often, weekly activities are organised for all residents who want to participate.

A student's room in Brussels. Credit: Belga / Justin Namurz

In private market kots, students usually also share the kitchen and showers with other students. This can be either in a shared house with a "kot boss", or in a larger residence. Students can also find studios (with their own kitchen and/or bathroom), but those are more expensive.

With Belgium's small size, those living in a student room tend to stay there during the week and go back home over the weekends. During the academic year, this frequently results in crowded trains to and from well-known 'student' cities – such as Leuven, Ghent, Antwerp, Liège and Brussels – on Friday and Sunday evenings, when most of them make the journey.

Generally, when going home on Friday evening, students take a suitcase of dirty clothes for their parents to wash. On Sunday evening, they then take the freshly laundered items back to their kot.

What's nightlife like for students?

As the majority of students go home over the weekend, the big evening to go out is not Friday but Thursday. While some big cities (such as Brussels) have nightclubs that students frequent, students mainly go out in bars – usually in a specific city area.

In Leuven, for example, the Oude Markt – with bars lining two sides of the city's main square – is a well-known student hotspot. In Ghent, the area around the Overpoort is the same. During the day, the bars function as normal but after a certain hour, the tables and chairs are put against the walls to make room for partying students.

Student clubs or associations are also a big part of universities' going out culture, as many first-year students consider it an easy way to make friends. They are usually linked to study programmes: medicine students normally join the medical student association, those studying economics tend to join the economic one. These associations organise activities such as sports events, movie evenings and nights out.

The student party area Overpoort in Ghent. Credit: Belga/James Arthur Gekiere

Most associations organise hazing rituals for new members seeking to join. While hazing rituals for fraternities, sororities and student societies are common around the world, Belgium's rituals tend to be more extreme. Some involve relatively harmless pranks, but others might be characterised as humiliation or abuse.

In 2018, one of these rituals at one of Belgium’s most prestigious universities (KU Leuven) made headlines as it resulted in the death of Sanda Dia, a 20-year-old engineering student who was being hazed to join a notorious male-only Flemish student club Reuzegom – home to the scions of Antwerp’s elites.

Although all 18 Reuzegom members avoided prison sentences, Dia's death sparked a reckoning at universities, with students increasingly pushing back against hazing. Now, the Flemish Union of Students (VVS) has introduced a new Hazing Charter, aiming to guide those planning an initiation ritual for their club.