As a bustling economic and political hub in the centre of Europe, Belgium is an increasingly attractive place to study, not only for locals but also a growing cohort of international students.

But as student numbers across Belgium are on the rise, university representatives say government funding is not keeping apace. They warn that their efforts to raise revenues elsewhere are constrained by red tape.

Growing student numbers

In the early 2000s, a little over one-third of 25 to 34-year-olds in Belgium had a higher education qualification. This has since risen to half of this age bracket, with the country's universities offering a broad range of subjects, as well as options to study through Dutch, French or English.

Françoise Smets, president of the Council of Rectors (CreF) which represents French-speaking universities, notes that their student numbers have expanded by 60% in the past 50 years, partly due to being easily accessible for international students.

“I think one of our strengths is that we are open and easily accessible for international students. This explains the really big increase in student numbers. It’s a strength but it’s also a challenge," she told The Brussels Times. She explained that a growing number of students have "limited financial means, which makes things more and more difficult."

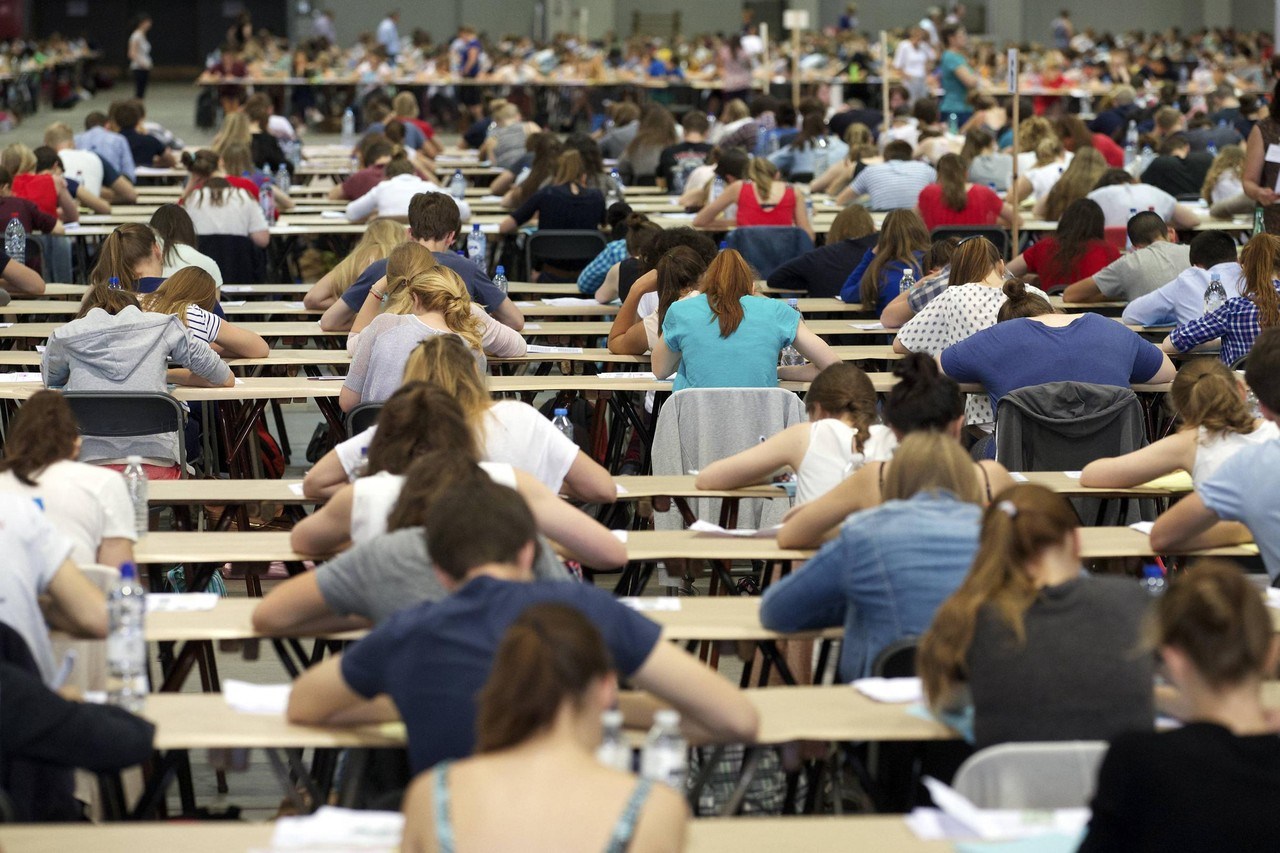

Credit: Benoit Doppagne/Belga.

The funding gap

Smets says that about two-thirds of the structural budget for French-speaking universities comes from the French-speaking community government (Fédération Wallonie-Bruxelles, FWB). The rest is made up of federal funding, research grants or private research contracts, and tuition fees.

But government funding has not kept up with the demands of rapidly growing universities, Smets warns. She argues that greater investment is needed to modernise teaching programmes, renovate ageing infrastructure, and support student welfare.

"There are solutions. We could increase tuition fees a little bit and we could try to work with the private sector. But we must do something soon."

Smets says tuition fees only make up a small part of university income (about 4% of the overall budget). Increasing the "very low" fees in Wallonia and French-speaking Brussels could seriously improve the funding situation, she argues.

"Our tuition fees are really, really low compared to other European countries. They have not been indexed in more than ten years. Even if you compare it to the Flemish part [of Belgium], it's much cheaper to study in the French system." However, raising fees is a decision that can only be made by the FWB.

For the 2023-2024 academic year, EU students at French-speaking universities paid maximum annual tuition fees of €835, rising to around €2,500 per year for students from outside the EU. In Flanders, annual fees for EU students are set at €1,092.10. Non-EU students can expect to pay over €7,000 per year.

"We don’t want to increase fees too much because we think it’s a strength to be quite easily accessible financially speaking. But right now they are really too low," said Smets.

Untenably cheap?

Koen Verlaeckt is Secretary General at the Flemish Inter-university Council (VLIR, the Flanders equivalent to CreF), which represents the five Dutch-speaking universities: VUB, University of Antwerp, KU Leuven, Ghent University and Hasselt University.

He agrees that the "erosion gap" in funding for universities is getting bigger: "The budget from the [Flanders] Department of Education is going down and the costs are going up. This is quite a challenge and forces our universities to look for additional sources of income," he told The Brussels Times.

Raising tuition fees is also something that Flemish universities are considering, but it is a decision to be taken by the government and one which would be seen as "political suicide", Verlaeckt said. "It’s a very sensitive topic. There are not many politicians who are willing to say 'Yes, we approve tuition fees being raised.'"

Students during university exams. Credit: Belga

Rigid language policies

Other options are boosting the number of international students, who pay higher fees, and winning more private research contracts from big companies with deep pockets.

In both cases, being able to study and work in English is key. But Verlaeckt says Flemish universities are hamstrung by "rigid language policy". By default, Flemish university courses are taught in Dutch. Current rules stipulate that if a programme is offered in another language – such as English – there must be an equivalent course available in Dutch.

Universities can make applications to drop the parallel Dutch-language course and only offer a subject in a foreign language. But the Flemish government has been known to deny these requests in recent years.

“The dominating party in the outgoing Flemish government – and most probably in the next government – is really sensitive to the importance of the Dutch language in higher education. Political parties say that we want to make our universities into English-speaking ecosystems, which is complete rubbish," said Verlaeckt.

"We’ve been hammering on this issue; we need to be more flexible. If you enforce a very rigid language policy and you ignore the international reality, it becomes extremely difficult for universities to come up with a substantial internationalisation policy."

Related News

- From Taylor Swift to electron microscopes: A guide to Belgium's research universities

- Going home on weekends? What university life in Belgium is like

As Dutch-speaking universities (much like their French-speaking equivalents) grapple with funding shortfalls, they will appeal to the incoming government to prioritise the issue in the next mandate, Verlaeckt says.

"We are waiting for the new government and this is one of the things we really push for. This is our number one priority, making sure that the gap between income and expenses is reduced as much as possible."