Sandwiched between France and the Netherlands – with Switzerland not far either – Belgium has not been well known among its neighbours for the quality of its cheeses. Yet that may be about to change.

“We sell around triple the amount of Belgian cheese now as we did 20 years ago – and interest is growing all the time,” says cheese affineur Frederic Van Tricht. His family have been running Kaasaffineurs Van Tricht, a speciality cheese shop in Antwerp, for half a century.

“When people think of Belgium, the first things that come to mind are beer and chocolate,” he explains. “But recently, Belgian cheesemakers have started to win awards at international competitions, and people around the world are starting to pay attention.”

The Van Tricht family now supplies Belgian cheeses as far as America, Dubai, Singapore, and the Maldives. “We often have international visitors in the shop – many of whom have come specially to try Belgian cheese for the very first time,” Van Tricht says. Recently he received an email from someone in China who had bought some cheese from the shop and enjoyed it so much he wanted a regular order shipped over to him in Asia.

And, while a few years ago, most Michelin-starred restaurants in Belgium relied mostly on French cheeses for their menus, an increasing number are now swapping these out for local alternatives. Tim Meuleneire, the chef at Hotel Franq in Antwerp, which received its first Michelin star last year, said he only works with Belgian cheeses because of the excellent quality of the local products.

“Our range of cheeses changes regularly throughout the year and is included in our tasting menu,” he explains. “Each has its own characteristics: hard, soft, mildew, red crust, ash crust, pasteurized or raw milk, with herbs or spices...you name it. The variety is what makes Belgian cheeses so exciting.”

Belgian cheesemaking matures

As interest in cheese has grown in Belgium, in 2017 Brussels even gained its first-ever dedicated cheese bar: La Fruitière.

Part of the reason why Belgian cheese has never taken off internationally so far lies in its small-scale production. While the French produce 1,600 different cheeses, Belgium makes just a few hundred. Chances for international notoriety are made even slimmer by the fact that most of these are made by individual farmers, producing very small batches each year, and few bother to export outside the country.

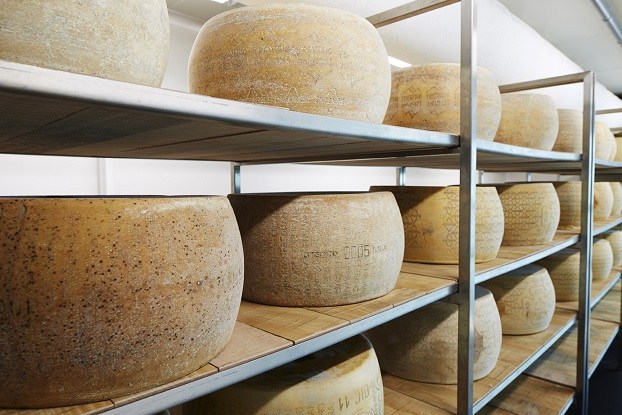

But it is exactly this artisanal quality that makes Belgian cheese so special, says Van Tricht. “These small producers are making cheese using the milk from the farm they live on. Nothing is factory-produced on an industrial scale, so the cheeses are unique and usually unpasteurised.”

Belgian cheese-making is starting to make a name for itself internationally. In the most recent World Cheese Awards, held in Bergamo, Italy, two gold medals, and several other prizes were awarded to Belgian cheeses.

Aside from its fresher taste, eating raw cheese has its health benefits too. It abounds in enzymes that help to digest the fats and proteins and is often much easier on the stomach for those who are lactose intolerant. Some research has even shown that the acids in unpasteurised milk may help protect against heart disease and cancer.

So why have Belgian cheeses been ignored for so long? It’s true that they have been somewhat disadvantaged by the fact that traditional snobbery puts wine as cheese’s perfect pair. France has almost 30,000 wineries – compared to just 20 or so dotted around Belgium.

But as palates, and opinions, have adapted, entrepreneurial Belgians have been capitalising on the opportunities. “Beer is often a much better pairing with cheese than wine – and people are finally starting to realise it,” says Van Tricht. His father, Michel, has published two books on cheese and beer as a combination.

“Cheese is rich and full of fats which cover your taste buds. If you drink something with carbon dioxide in it, like beer, it breaks down the fat – whereas the tannins in red wine will simply fight with the cream in the cheese,” the younger Van Tricht explains. The bitterness in beer also cleanses your palate – so you feel like eating more, no matter how strong or stinky the cheese.

“You have such a huge range of beers: sour, bitter, sweet – but rarely salty. As cheese is often salty, it contrasts well.” Van Tricht’s favourite combinations are ones that bring together all four flavours, for example an amber beer with caramel malts paired with a fresh salted goat’s cheese. “There are also some surprising combinations that work really well such as sour cherry beer with a strong blue cheese,” he adds.

Beer and cheese, please

Belgians in particular are latching on to this new taste for beer and cheese and even combining the two into one product. The Van Trichts recently created two new types of cheese using exactly the same dairy base but adding two different beers. “You wouldn’t believe how different they taste.”

Apart from a good partner, top quality cheeses also require good presentation. At La Fruitière, Brussels’ first ever dedicated cheese bar, customers are encouraged to eat their wares on the spot. There is no set menu – you simply explain what flavours you enjoy and Véronique Socié, the award-winning cheesemaker and shop owner, will make her recommendations from behind the bar.

The combination of pairing beer and cheese is gaining interest, with new dedicated cheese bars popping up in Brussels and the rest of the country.

“To recommend the right cheese, you have to find what makes that person tick,” Socié explains. “And we would never serve a cheese if it’s not mature. We have four different caves for ageing and storing, all of which are kept at different temperatures and humidity levels depending on what we have at that time.”

Although she sells everything from Quebecois rind cheeses to Greek fetas, local products feature heavily. She too has noticed a growing interest in Belgian cheese, which, she says, is being driven by the experimental work of local farmers and the movement towards more artisan methods.

This innovative spirit shown by Belgian cheesemakers has not gone unnoticed outside the country. At the World Cheese Awards 2019, where 3,804 cheeses from more than 40 nations were pitted against one another, Ghent-based cheesemonger Kaasimport De Kaasboer took home two gold medals. One was for his Maigre Du Nord, made from heated but not quite pasteurized goat milk, and the other for his Gentenaer cheese.

The year before, Belgians scooped up even more of the prizes. The judges were particularly impressed by the mimolettes and Flandrien cheese, previously crowned the world’s best Gouda, made by family business De Kazerij, as well as the Groendal family’s slightly caramelised Old Groendal.

Though it is only recently that Belgium has gained recognition for a cheese-producing nation, the history of cheese in the region stretches back a long way – before the country was even formed. In the medieval times, trappist monks would turn the milk from their cows into cheeses, often smearing them in the alcohol – either beer or spirits – they were brewing at the same time. Some modern-day monasteries still continue this tradition.

More recently, the Belgian clergy have continued to make their mark on the world of cheesemaking. In the early Sixties, a Brussels missionary became the first man to introduce the dairy product to South Korea. When Belgian priest Didier t’ Serstevens taught local farmers, who had been impoverished by the Korean War to make cheese from the milk of their goats, Korea's first ever cheese, called Imsil cheese, was born. It is now sold to 70 different brands and the company makes a profit of around €20 million per year.

In recognition of his contribution to local culture, when t’ Serstevens died last year, his funeral was attended by 1,000 Koreans. There is even a theme park dedicated to his cheese where you can go on rides, make cheeses and visit a science lab that researches different methods for making the best cheeses.

While Brussels is unlikely to see its own cheese-dedicated theme park in coming years, it just goes to show that Belgium has much to be proud of when it comes to its cheeses and, if today’s generation of cheesemakers have anything to do with it, there is still far more to come.

By Marianna Hunt