It’s the morning after an all-night recording session at Studio Katy, a music studio in Ohain, near Waterloo in 1982. Marvin Gaye is riding shotgun in a blue Mercedes saloon heading back on the motorway to his temporary home in Ostend, driven by his Belgian friend, the concert promoter, and the man who tried save his life, Freddy Cousaert.

During the drive, they chat about the upcoming album. Cousaert asks the singer who he most wants to listen to it. “Above all my father,” Gaye replies. Two years later Marvin Gaye, one of the greatest voices in soul and pop, was dead, shot in the heart at point blank range by his father Marvin Gay Sr, a cross-dressing Pentecostal preacher. He died a day shy of his 45th birthday.

Gaye (he added the ‘e’ to avoid confusion about his sexuality) had his demons. Along with his prodigious talent as a singer, performer and song writer, he was addicted to drugs and sex, and he suffered from severe depression that sparked paranoia and psychotic episodes.

He was in a deep depression the day he died, and according to his father it was a mercy killing carried out at the wish of the singer. Gay was initially charged with first-degree murder, but the charge was later reduced to voluntary manslaughter. He never went to prison.

How Marvin Gaye ended up in the Belgian coastal city of Ostend is one of the most unlikely episodes in popular music history.

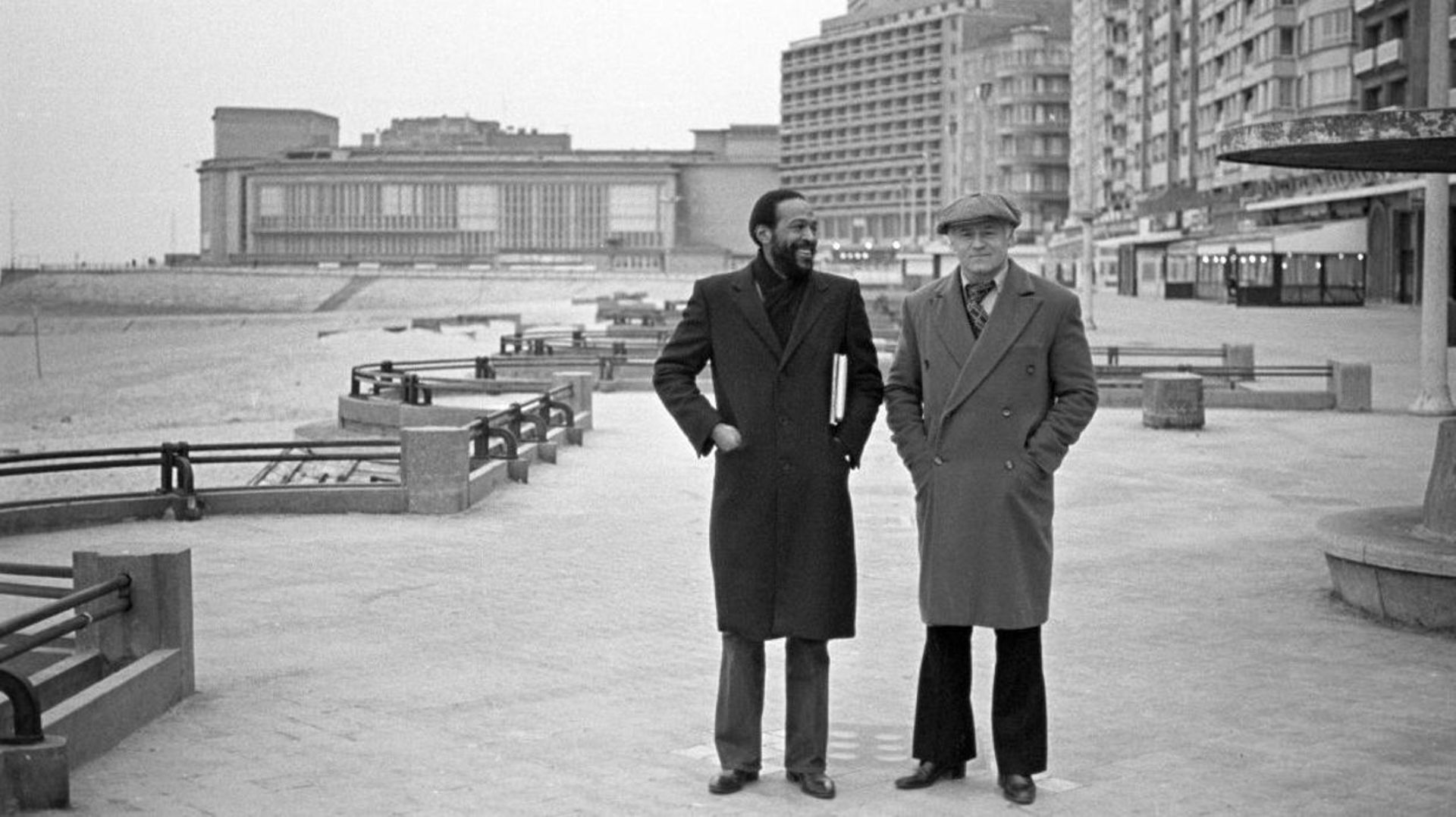

Walking on Ostend beach with a TV crew

Dubbed the Prince of Soul, Gaye is today hailed as a creative genius. Born in Washington DC, the singer-songwriter helped shape the sound of Motown in the 1960s, first as an in-house session player and later as a solo artist with a string of successes like I Heard It Through the Grapevine, It Takes Two and Ain’t No Mountain High Enough.

His career had already taken a turn in 1971 when he released the landmark concept album What’s Going On that captured the unsettled mood of the time with its title track and the song Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology).

But by the time his ferry docked in Ostend on a cold day in February 1981, he was burned out. Despite hits like Got to Give It Up (infamously sampled by Robin Thicke in 2013), his life was fraying. On top of the drugs – cocaine, alcohol and cannabis mainly – he was also getting over his second failed marriage and was coming to terms with the acrimonious break-up with his record label Motown. On top of all that he owed over $4 million in back taxes in the United States.

Ostend rehab

He had met Cousaert in Britain where Gaye had been touring and hiding from the tax man. The two instantly became friends. Cousaert invited the singer, his five-year-old son Frankie, known as Bubby, along with his Dutch girlfriend and babysitter Eugenie Vis to live with him and his family in Ostend.

He wanted to help Gaye get over his addictions, and to kick-start his faltering musical career. Where better to get cleaned up than in a sleepy seaside resort in Belgium?

Cousaert succeeded in the second goal at least. Midnight Love, Gaye’s 17th and final album, was mostly written and recorded during his 18-month stay in Belgium. It marked a return to form after a gradual decline towards the end of the 1970s, and the album’s double Grammy award-winning single Sexual Healing, composed in an Ostend seafront apartment was his biggest ever hit.

Sadly, Cousaert didn’t succeed in saving Gaye from himself. But it wasn’t for lack of trying.

Freddy Cousaert with Marvin Gaye

Gaye described Ostend as a place where he didn’t want to be but needed to be. He said he was an orphan, and the seaside city was his orphanage.

Pascale Cousaert, Freddy’s daughter, who was 14 when Gaye came to stay, shines new light on this period.

Gaye wanted to stay longer in Belgium, she tells me. His tourist visa was about to expire but she thinks that wasn’t the reason he left. That would have been easy to fix. More likely, he was lured back to Los Angeles by his narcotic demons. He knew that Ostend was good for him, which is why he planned to buy a house nearby.

He and Freddie Cousaert jointly paid a deposit in Belgian francs, the equivalent today of around €25,000, on a villa near Gistel, a town a few kilometres inland from Ostend. He had been staying in Ostend, but the neighbours were complaining about the noise at night – the music mainly. Gaye lived in the villa for some months before leaving Belgium but as a tenant, not the owner.

Pascale Cousaert claims Gaye and her father were tricked by a lawyer representing another local resident, Charles Dumolin, who owned the villa.

According to locals Dumolin was a dabbler. He wrote Belgium’s 1979 Eurovision entry (Hey Nana, performed by singer Micha Marah; it came last), and he made the only visible trace of Gaye in Ostend, an unflattering muddy bronze coloured statue of the singer at the piano. For many years it was housed in Ostend’s Kursaal concert hall. In recent years it was moved to less glamourous location, a small shopping mall outside the city centre.

Dumolin died in 2019 and to many locals, he is remembered as the man who ripped off Gaye.

His lawyer, Alex Trappeniers, is still around. He made headlines around the world in March this year when he claimed that Gaye left his possessions to the Dumolin family, including 30 cassette tapes which Trappeniers claims contain recordings as significant as the Sexual Healing hit.

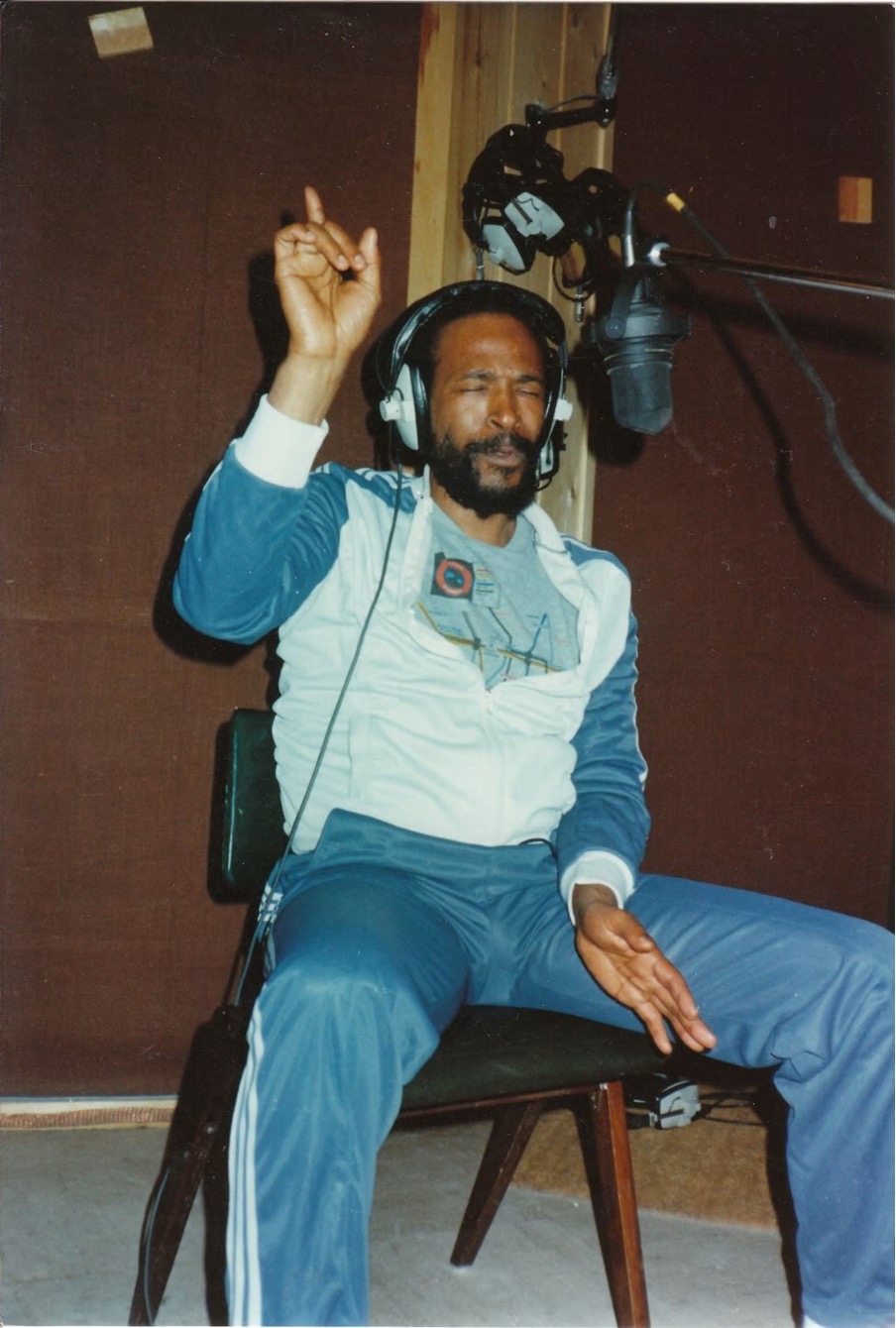

Marvin Gaye records in Ostend

"When I had listened to the thirty tapes, I had 66 demos of new songs," Trappeniers told the BBC in late March. "A few of them are complete, and a few of them are as good as Sexual Healing,” he said.

Gaye also left some clothes including stage outfits, a track suit as well as accessories including cufflinks, shoes, ties, braces and several ornate beanie-style skull caps that the singer was often photographed wearing. All these items can be seen on a website Trappeniers set up, marvinbelgium.com, and are set to be auctioned online.

But Ostend locals have cast doubt on Trappeniers’ claims of a lost Marvin Gaye hit. “It’s bullshit,” says Pascale Cousaert. She is angry at the Dumolin family and Trappeniers for trying to cash in on Gaye’s Ostend period.

“We saw the tapes. In my opinion, talk of a lost hit is just a strategy to push up the price of the things the Dumolin family plan to sell at auction,” says Pieter Hens from the Ostend tourist office. No-one apart from the Dumolin family and their lawyer has actually heard the tapes.

Publicity stunt

Trappeniers is reluctant to discuss the matter ahead of the auction. He refused to comment on claims that the cassette tapes story is a publicity stunt. “People in Ostend have their opinion,” he told me. “There will be a new statement but for now I have no comment.”

Pascale Cousaert doubts that Gaye bequeathed anything to anybody, but especially not to the Dumolins. "The idea that Marvin would just give his belongings away to someone doesn’t sound like him at all," she says, adding that if he ever gave anything away, Charles Dumolin would have been the last in line, after what happened with the villa.

Reflecting on the time Marvin Gaye came to stay, Pascale has a mix of feelings. “I felt warm towards him at the time but not anymore,” she says. “With all that happened, the way he left, without a word of thanks.”

“As a man he was not appreciative towards people he was close to and he hurt many people,” she says, and refers to Odell Brown, the keyboard player who helped Gaye write Sexual Healing but was never credited for it in the sleeve notes.

Danny Bossaer, a guitarist from Ostend also wrote riffs that appeared on the Midnight Love album, but who was dropped like a stone when the recording sessions in Ohain began. Bossaer did not respond to requests for comment. “It’s hard to talk to him about it,” says Bobo Kool (aka Alain Verkouille), a long-time friend of Freddy Cousaert’s, and a fellow soul music fanatic, who runs the Lafayette bar and club in the centre of Ostend.

Then there was Eugenie Vis, who was deeply in love with Gaye. He dropped her with no warning, Pascale says. “That’s a sad story. She later committed suicide,” she says.

But her lack of warmth for the memory of this great singer is mainly due to the way Gaye treated her father. Freddy Cousaert negotiated a three-album contract with Columbia Records on behalf of the artist. Only one album was recorded but Freddy can fairly claim to have – temporarily at least – helped Gaye over some his addictions and revive the artist’s flagging career.

“Columbia at least acknowledged my father’s role. They sent him a gold copy of the Midnight Love album. Marvin didn’t say anything,” Pascale says.

Teenage thrill

But it was a thrilling time for a teenage girl having such a charismatic and handsome house guest. Was she a little in love with him? “Not at all,” she says, laughing. “It was like having a second dad in the house. He’d always say ‘do what your dad says.’”

She says she never saw any sign of his depression. Nor was there any sign that he was on cocaine. On the contrary, Gaye was living quite healthily. He boxed regularly with Freddy Cousaert’s brother Louis at the Royal Stables gym, he was often spotted jogging on the beach, and praying at the Sint-Petrus-en-Pauluskerk near the port. But he wasn’t teetotal. “I saw him and my dad quite drunk a few times. His favourite beer was Bush,” Pascale says.

Nor was he celibate. She was aware of his obsession with sex. “I heard from my mum that he was into very kinky sex with Eugenie. And I remember one time I went into his room looking for our cat. I remember seeing porn magazines everywhere,” she said.

A bronze statue of the late singer Marvin Gaye. Credit: Belga

A picture of Ostend emerges from this unusual episode in music history. Strangely, there’s almost nothing from Marvin Gaye’s time there to see. The Ostend tourist board promotes a smartphone app that guides you on a pleasant walk on the promenade and to places nearby where the singer lived, worked out and some of the bars where he drank. That’s it, apart from an ugly bronze statue hidden in a shopping mall.

It’s a peculiarly Belgian trait not to make a song and dance. Pascale says there was talk of opening a Hard Rock Café-style bar there some years ago but it never happened. Pieter Hens from the Ostend Tourist Board said there was also discussion about opening a Marvin Gaye Museum but there wasn’t enough material to show. What about the paraphernalia being auctioned? Doesn’t it deserve to be put on public show?

“It seems they have other plans,” Hens says, referring to the Dumolin family and Trappeniers.

And while much as been written about Gaye’s Ostend sojourn, there remain interesting questions about the singer. Was he so keen for his preacher dad to hear the new album because he wanted to shock him? Or was he desperately seeking a father’s approval?

“I think it was because he wanted his father’s approval. He got it from his mother but never from his dad,” says Pascale who is still in contact with the Gaye family today.

If the tapes do contain great unheard music from Gaye, then we’ll hear about it soon enough. Trappeniers told Flemish daily newspaper De Morgen that he hopes someone like Mark Ronson, Dr. Dre or Jay-Z will work with the material to bring it to life. He had just flown back from LA the day I spoke to him.

But if it exists, and if they do, then they will have to talk to the Marvin Gaye estate, not a canny lawyer from West Flanders. The Dumolin family may own the tapes but they don’t own their content.