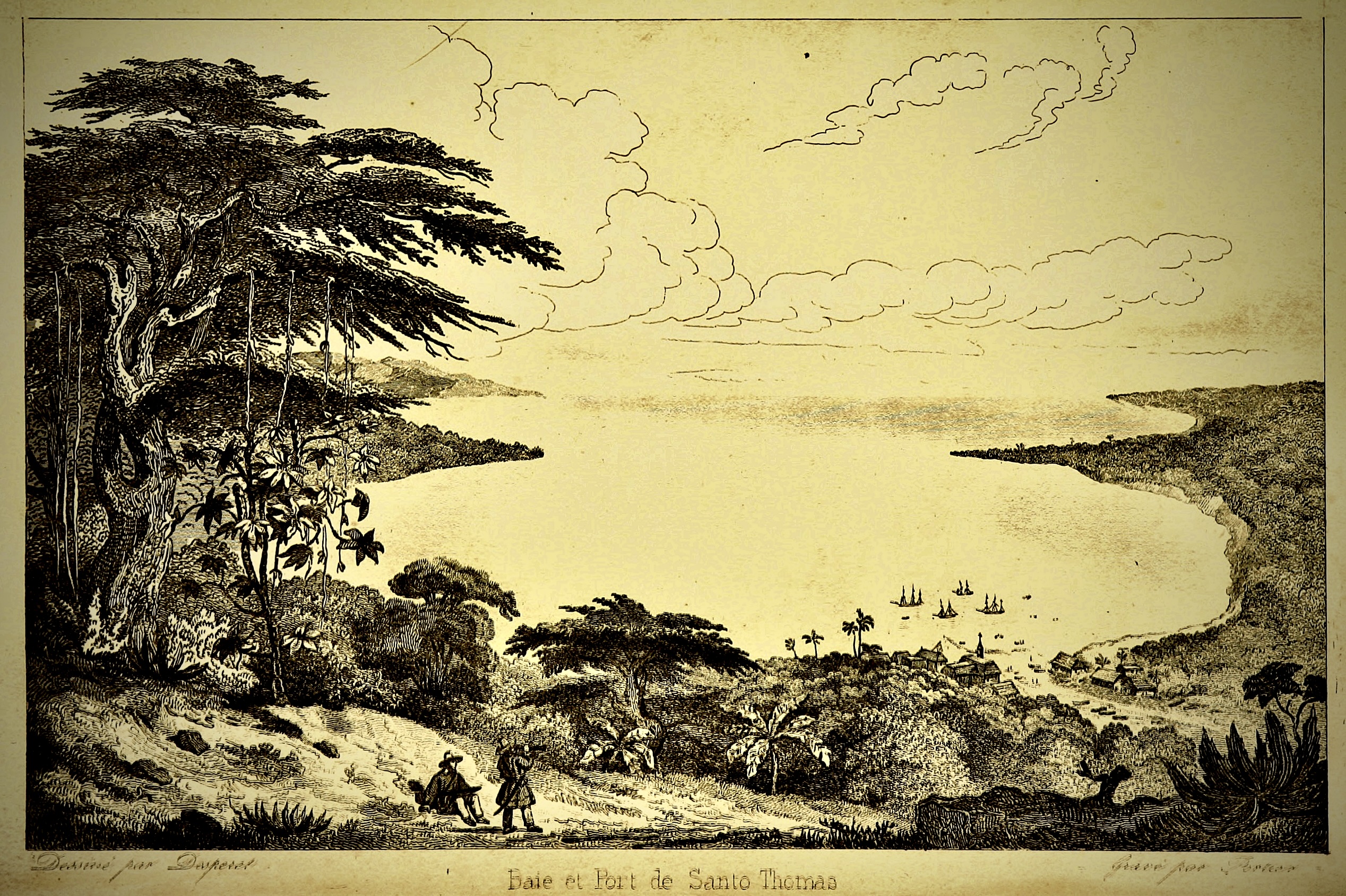

"We are surrounded on all sides by magnificent forests with trees of immense height,” a Belgian official noted. Frigate birds, pelicans and white herons flittered above the surface of the bay’s immense crystal-clear water basin. Legions of fish with glistening scales and menacing shadows of gigantic sharks could be seen clearly above water. “All the officers agree that this is the most beautiful and convenient port they have ever seen.”

This was a forgotten empire story – not taught in Belgian schools – of a tropical paradise in Guatemala invaded by a caravel of Belgian colonists intent on striking gold in the Caribbean, egged on by the young country’s ancient elite.

The ships that sailed from the Port of Antwerp across the Atlantic to dock at the bay of Santo Tomás in Guatemala, brought hundreds of hopeful settlers to their tragic death. They were consumed not only by the scorching conditions of the jungle but by the colony’s chaotic administration which became dominated by a power struggle between the military and religion.

In the early 1840s, wealthy European nations built and flaunted power by establishing colonies for exploitation, and King Leopold I was keen to consolidate his new Belgian State’s place on the world stage. He advocated for new colonies that would bring wealth and create “new, glorious” opportunities for Belgians – while also hoping that it would help to alleviate some of his domestic problems. Belgium found itself during this period in a deep industrial crisis, compounded by a growing population and a food shortage from poor harvests, with the infamous potato blight striking in 1845.

Hoping to turn the country’s fate, the Belgian Colonisation Company was founded in 1841 to administer a future colony. The Company set up a mission to Central America to see whether the foundation of a Belgian colony was “practicable and desirable”.

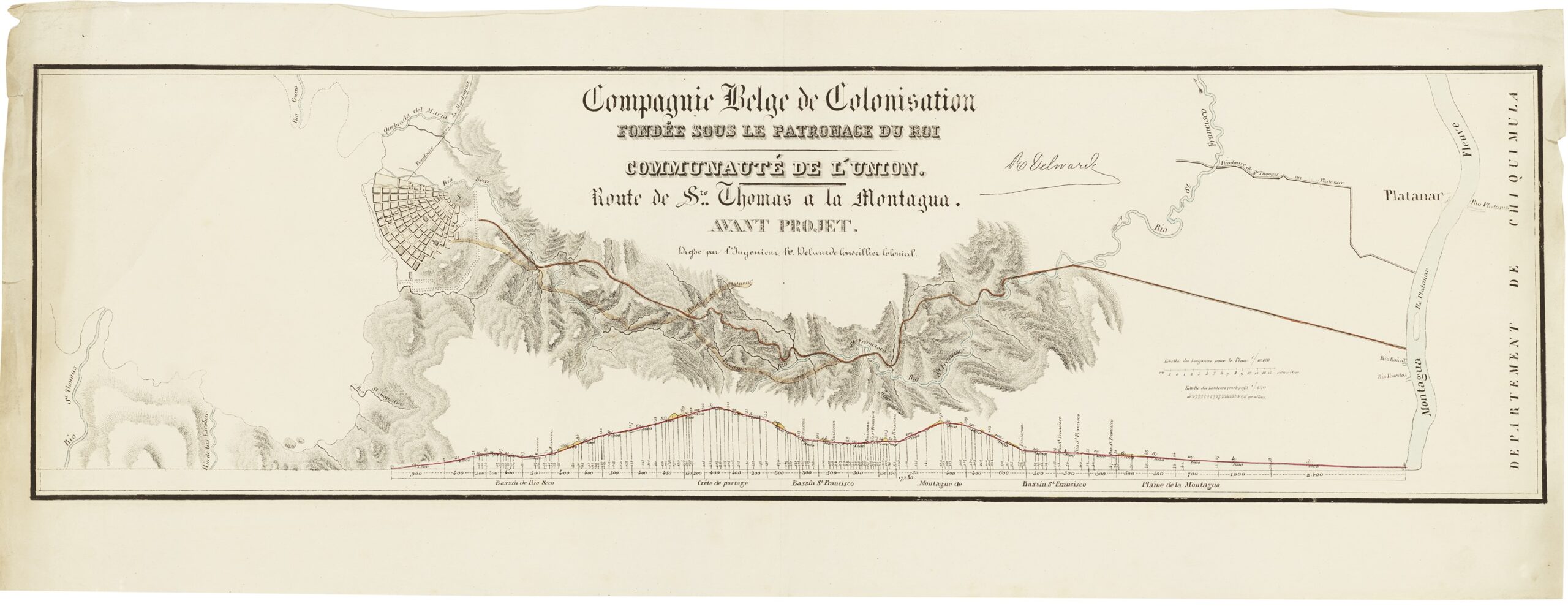

They settled on Guatemala, which had secured its own independence from Spain and Mexico in 1821, a decade before Belgium. Guatemala’s horseshoe-shaped bay of Santo Tomás on the Atlantic coast was identified as the most suitable choice for the new colony.

What the officials missed was that the bay was situated off a famously inhospitable stretch of coast. The coastline insurance for ships travelling through was higher due to the devastating tropical storms and shipwrecks.

The Guatemalan government granted Belgian investors the chance to purchase 264,000 acres of underdeveloped land, five kilometres in diameter. In return, Guatemala would benefit from the construction of a port and other key infrastructure, while the Company received various tax exemptions. Upon arrival, all Belgian colonists automatically became Guatemalan citizens but would be exempt from taxes for 20 years.

Upon their first visit, Belgian officials concluded in their report for Brussels that the area was a “most tranquil haven”. They lauded the endless possibilities for a prosperous Belgian colony, speaking positively of the climate and lack of diseases.

British settlers were also in the area, and the two officials described the scene at the settlement at Abbotsville: “The English colony is in a miserable condition, most of the settlers do not work: they are idle drunkards and lead an irregular life.” Rather than heeding any potential warning signs, the officials put it down to bad management.

New colony, new chapter

Belgian Prime Minister Jean-Baptiste Nothomb and his cabinet threw their weight behind the colonisation company. A year after its establishment, the Company secured a loan from the government, which put at its disposal railway materials, senior engineers, paid army officers, state-owned ships and weapons. At first, only a few people would be sent to Santo Tomás to “employ the natives in cutting down the woods, clearing and sowing the ground for the first settlement, and erecting habitations, not for 100 settlers but only for 25 or 30, with their families, who will not set out till at least two months after,” the Morning Post reported on October 1842.

Louise Marie ship leaving the Port of Antwerp

The following spring, on March 16, 1843, the Louise-Marie, the Ville de Bruxelles and the Theodore ships set sail from the Port of Antwerp with the first group of colonists and supplies. The project had taken on a national character, with King Leopold and the government zealously promoting the new colony as a new chapter in “the evolution of mankind and the establishment of the Belgian nation.”

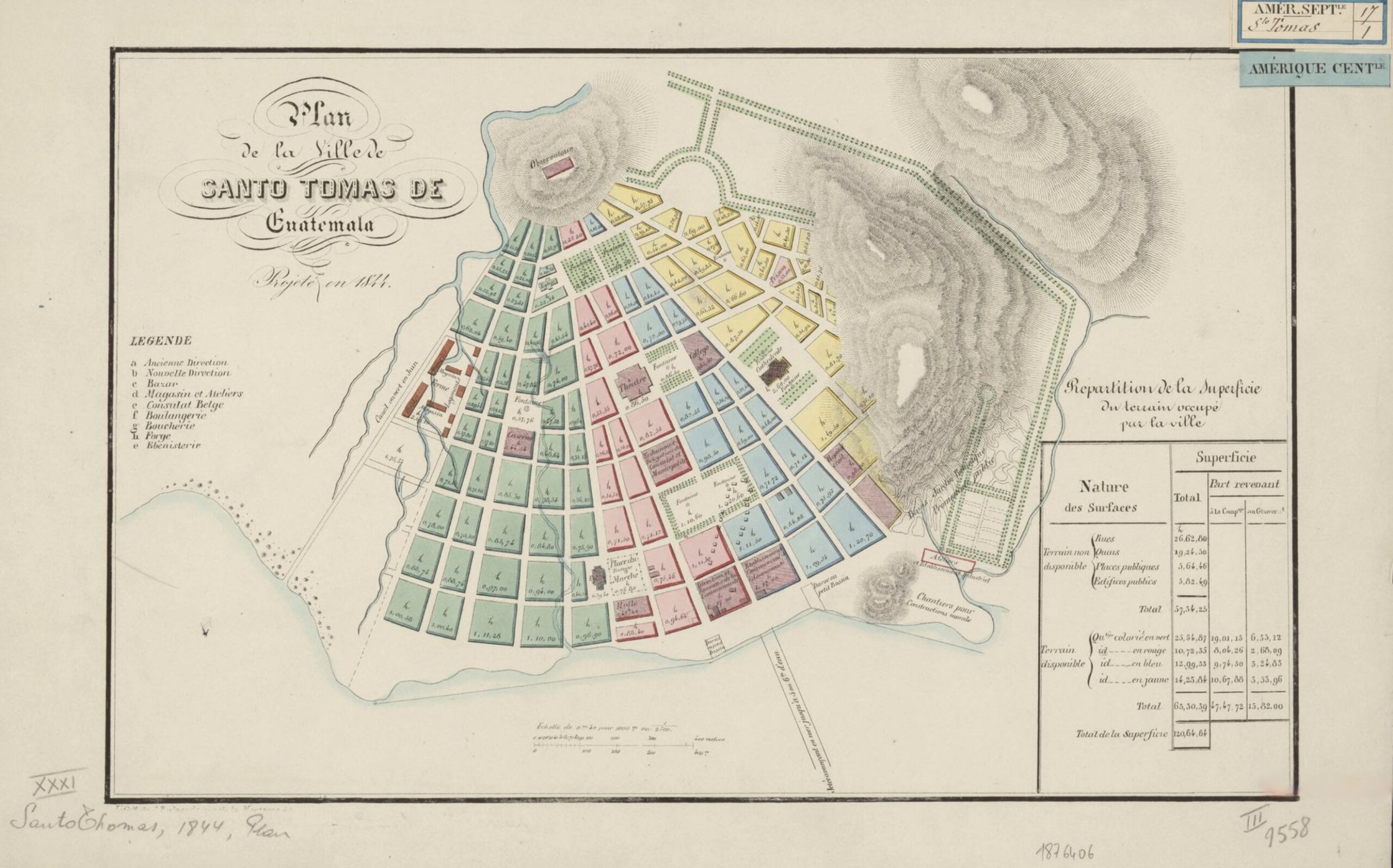

Despite having the blessing of the Belgian crown, the small colony was run through a communitarian system, under which the Company created the Community of the Union to govern it as a separate entity. Divided between workers and capitalists, the latter could buy one of 8,000 community titles, which gave them 20 hectares of land, outside of the exclusive territory of the Community of the Union and were free to use the land how they pleased. The community titles would fund the operation of the colony. Workers would get a salary and access to a small share of the profits, which were distributed annually.

In practice, colonists were forced to work for the administration and could only spend their wages at the company's shops through the purchase of food and clothes. Under this system, the settlers would have had to work for 20 years for the company, after which they would each have been given a hectare of “virgin forest”, later calculated to be worth just two francs. Nor was the system truly communitarian, as it only applied to the Europeans and not the Guatemalan workers. The Community of the Union was based on the exploitation of labour organised according to race (indigenous, Caribbean and Creole), with each race specialising in a particular type of task, mostly in the export of wood, and were regularly paid in kind – sometimes in bananas.

Map of the Belgian colony of Santo Tomas, Guatemala, in 1844. It shows the division of land for colonists.

While the mission was an interplay between the commercial interests of the Belgian elite and geopolitical aims, both poorly defined, it was underpinned by a “civilisation mission” led by the Jesuits in the colony which was rooted in racial superiority.

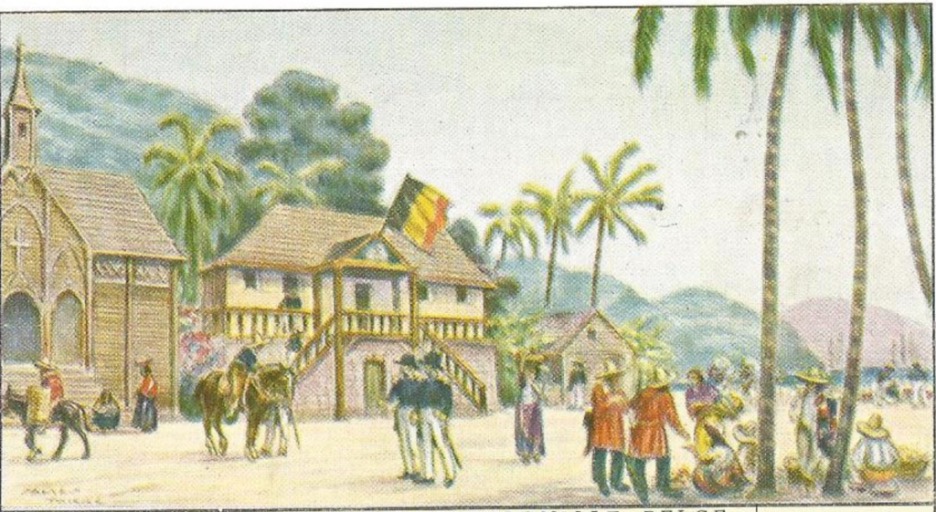

The Jesuit mission was one of many contradictions. Rather than seeking new souls to convert, their system entrenched inequalities between colonists and local Guatemalans. Instead of welcoming locals, a Jesuit leader had three indigenous families chased from their homes after they built their huts close to the settlement. A small chapel was brought over from Belgium to be fully reconstructed, although it was never fully completed. They even established a Grand Place in the main square of the settlement.

Instead of building infrastructure to sustain the colony, Belgium sent many young adventurous but inexperienced citizens there: farmers, unemployed factory workers and small-scale traders. There are also theories that Santo Tomás was used as an unofficial penal colony for Belgian society’s undesirables.

Meanwhile, on the strength of misleading reports sent to Brussels of a prosperous new Belgian colony, ships with new arrivals continued to leave for Santo Tomás. By October 1, 1843, the colony had 821 settlers, including an increasing number of soldiers and sailors. Colonial enthusiasm back home was growing.

Arrival in ‘our new homeland’

The diary of one of the first Belgian settlers, Charles Van Huyse, described the scenes they witnessed as he and his fellow Belgians first set eyes on Santo Tomás:

“On May 19th, around 4pm, we anchored in Santo Tomás Bay. What luxurious greenery. We felt we were in a new Eden. Extremely tall, massive trees seemed to grow up from the rocks straight up into the heavens. We were bewitched. Long live Santo Tomás, our new homeland.”

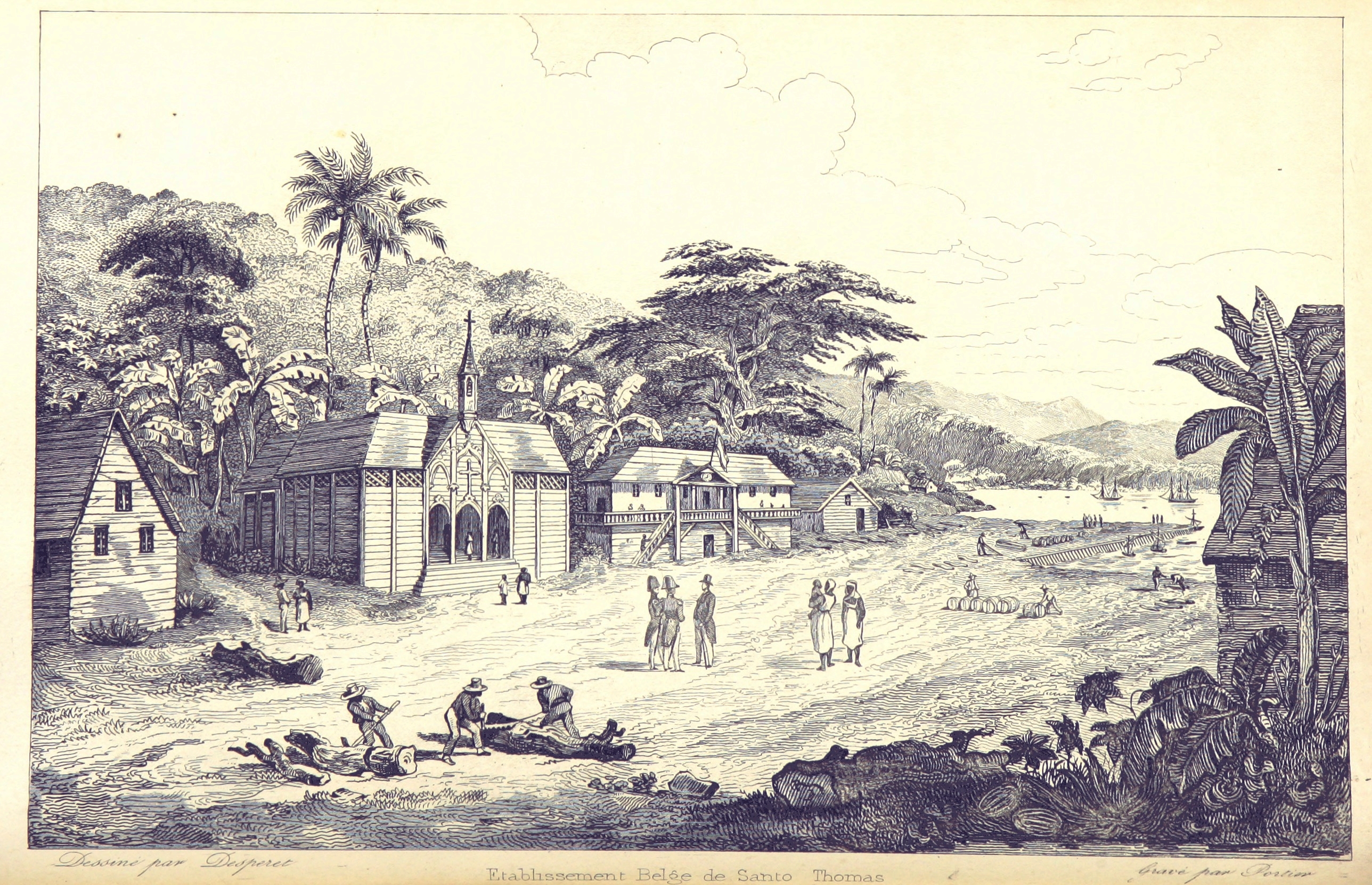

Bay and Port of Santo Tomas during the Belgian colony

But during the voyage, the first serious blow had already been dealt to the colony. The colonial director and engineer Pierre Simons died in May 1843 on board the second ship which had left for Santo Tomás. Simons had been one of the pioneers of the world-leading Belgian railways, and this early loss of leadership was devastating. To make matters worse, most of the colony’s key supplies were on the second ship which did not arrive for another three weeks after being blown off course.

On May 24, Van Huyse wrote in his diary how he and his fellow Belgian settlers finally took possession of the land. Each man had his gun, sword or machete – some even had a spade or a pickaxe – but encountered no resistance. The colonists were made to camp “in the middle of nowhere,” and were assaulted by the local fauna: “An army of winged Philistines, the mosquitoes, let us not a minute’s peace. Ants and other rapacious insects….attacked us in all possible ways. People kept scratching arms, legs, thighs, noses and ears.”

Jesuit control

Following the death of Simons, the management of the colony was entrusted to the ardennais Jesuit Father Walle, rather than the preferred army Captain Philipot. The Jesuits had already proved themselves unpopular for their religious zeal on the voyage over, and the decision made by the Director of the Belgian Colonisation Company Count Theophile von Hompesch back in Brussels was widely resented in Santo Tomás. Contradictory instructions from the Company’s leaders were common.

The Prussian baron Alexander von Bulow was second in command, a man who enjoyed playing the lord. Charles Van Huyse’s diary details the gross mismanagement and despotic negligence of their superiors. On the third day, Baron von Bulow made all the settlers dig holes in the ground to store barrels full of smoked meat, peas, beans, potatoes, prunes, barley, rice and flour. Van Hulse dryly related the inevitable result:

“Some colonists with more experience than the clever Baron pointed out to him that the meat would rot underground. But he neglected the advice and forced them to obey. Two days later we had to dig up the provisions. It was full of ants, and all we could do was dump it in the sea.”

Street scene in the Belgian colony of Santo Tomas, including the wooden church on the left.

The squandering and indifference to the means of subsistence seriously alarmed the settlers. Eight days later, a merchant bought a dozen cows purchased by the Baron. “We were all overjoyed. Hope was revived in our hearts, which had been so tormented by fear and disappointment.” However, after the cows had been killed, one of the Jesuits pointed out that it was Friday, and he forbade the colony to put the meat on the spit under penalty of mortal sin. The next day, the meat was rotten. “That’s the result of being a good Catholic in a wild and deserted country,” Van Huyse wrote.

The colonists were also promised that they would find ready-built shelter upon their arrival but only found one rickety shed with half a roof. When they stumbled on three empty huts, large enough to house the settlers, the Baron said he loved the view and claimed them as his summer residence, creating English gardens and other expensive embellishments. There was no further talk of a hospital or a shelter for sick people and convalescents.

As the settlers became discouraged, the work ethic and output of the colony plummeted. Van Hulse continued:

“Our dreams were shattered. Our solidarity turned into dissension. Instead of uniting our forces, they became divided. However, exile should lead to equality….The confidence we felt on leaving had been totally eradicated by the injustice and the indifference of our leaders. We felt betrayed and abandoned by everyone.”

Van Huyse was thrown out of the colony in December 1843 over an altercation with a policeman. Meanwhile, the colony continued to grow too quickly. The colonists had barely built enough suitable accommodation, with tumultuous storms destroying the ramshackle huts and insalubrious barracks covered in manaca (local palm leaves). During the rainy season, the town was full of potholes which created stagnant pools. Many new arrivals had to settle for makeshift accommodation, resulting in a generalised low morale.

The colony struggled with the humid climate and, with few distractions available, the population turned to drinking. They were encouraged by the Belgian ships that arrived every month packed with copious quantities of wine and spirits. According to a Belgian consul who later came to investigate (after the departure of the repressive Father Welle), Santo Tomás still lacked basic infrastructure but had a two-storey cabaret. The colony’s doctor had become a drunkard, leaving the sick to their fate as he spent his days lying in his hammock and his evenings drinking. One night, a few colonists found him in the middle of the main square as “drunk as a skunk”.

Many directors passed through the role, all as inept as each other. The suicide of Captain Philippot in November 1844 was another warning sign that something was amiss. Major Guillaumot, who took his place, was a brutal French general who vowed to install order “militarily” and denigrated Philippot as a “deserter". He insisted on bringing his brigades of Belgian pontoons, who occupied the coast militarily in breach of the agreement with the Guatemalan government.

Guillaumot noted the state of disorder upon his arrival: "Food and supplies had been scandalously squandered; tools, books, instruments and transportable objects had largely disappeared; the rest was scattered in the huts.” The major soon clashed with the colonists after his men started disrupting their habits through the enforcement of military checkpoints. Strict rules were brought in, to be adhered to by everyone, with heavy punishments being given out as accusations of cruelty and dictatorship grew. Many soon left because of Guillaumot's militarisation of the colony. The major struggled with the stream of new arrivals, as well as the tensions with the power of the Jesuits, and before long sent his resignation to Brussels.

Tropical inferno

Things continued to unravel and the settler population was soon engulfed by its most existential threat: a deadly outbreak of tropical diseases. The less well-travelled European immune systems were not helped by the colony living in destitution. A lack of hygiene was a constant severe threat to the colonists' health, with many dying as a result. In a bid to escape the chaos at Santo Tomás, some temporarily moved to Omoa, a port in Honduras, 100km to the southeast. The port was said to have been one of the most unsanitary spots on the tropical coast with endemic yellow fever and malaria.

Travelling between the port and the settlement, colonists brought back these diseases which were then spread around the colony by local mosquitoes residing in the Santo Tomás ponds. An epidemic was declared in July 1844, in which 219 settlers died. By May 1845, after the many deaths and the dispersal of frightened settlers to the mainland, only around 200 colonists remained, with the number of orphans having risen to 85. It had, at one time, exceeded 880 European settlers. The majority were Belgians, followed by sizable German and French communities, a handful of Dutch people and one Swiss national.

As news of disease and death reached Brussels, the fuse was lit for the ensuing scandal. As the colonists returned home and revealed the true conditions of life in Santo Tomás in the press, the narrative of a thriving Belgian community in Guatemala was quickly replaced by growing anger against the government and the Belgian Colonisation Company.

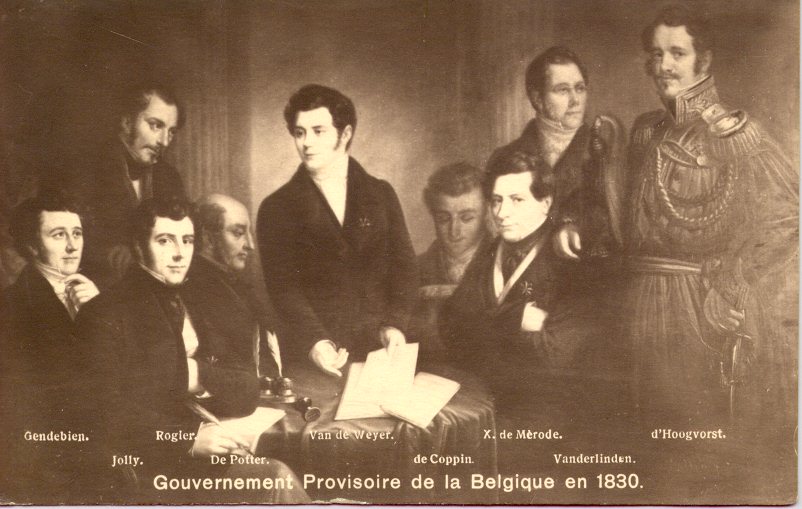

Opponents of the colony Gendebien and Rogier, seated with de Merode, a key supporter in the provisional Belgian government of 1830

Liberal politician and revolutionary hero Charles Rogier stood up in the Belgian parliament and called Santo Tomás a country of “misery” where “serious complaints were raised against two officials and the government did nothing.”

A letter in 1844 signed by Alexandre Gendebien, a leading Belgian revolutionary, MP and lawyer, furiously queried how a country forbidden (under the terms of its constitution agreed with its allies) from establishing a military navy was hoping to find success in any colonial projects. He lambasted the Belgian government for having convinced its citizens to embark on such a disastrous adventure. “The mystification is not only cruel, it is criminal if this beautiful, fertile, industrious country transplants a part of its population in a homicidal climate,” he wrote.

Gendebien further protested that “a country cannot improve its culture by reclaiming uncultivated lands” and “transplanting” a part of its workers into other people’s lands. “It abuses good faith, deceiving itself, when it presents this deplorable deportation as a means of creating consumer opportunities for national industry,” he said.

There were also furious criticisms of the wasted capital. In 1845, a fed-up Belgian Minister of Finance Edouard Mercier criticised his colleagues for so zealously supporting the Belgian colony in Guatemala to the detriment of national finances. As an example, he cited the government’s deal to sell the Colonisation Company 125,000 francs worth of guns and cannons, and when the bills for payment were overdue and remained unpaid, the contracts were still renewed.

A cannon which was left behind by the Belgian colonists

Some returned, some hung on

In 1847, a ship set sail for Santo Tomás to bring back Belgian colonists. When it landed on April 25. 1847, it found the situation to be slightly better than feared. Out of 210 inhabitants, only 63 agreed to return home. Over time, the Guatemalans began to mistrust the Belgians, who had mistreated the local inhabitants, particularly women, and brought the smuggling and sale of goods (including much alcohol) that was highly detrimental to national trade and local markets.

The colony would continue into the 1850s, but during its final period, there were never more than 100 settlers at any one time. Last-ditch efforts were made to save it, with even the Guatemalan government being moved to intervene and send a governor to restore order. With production low, bad living conditions and morale at rock bottom, the colony’s losses were piling up. King Leopold lost all the capital he had invested.

One of the founders and director of the Company, Count Théophile de Hompesch, had advanced considerable funds he would never recover. His story may best symbolise the hope and anguish of the company’s failure.

After resigning in 1845, de Hompesch fell seriously ill the following year and was pursued and harassed by creditors. De Hompesch sued the Belgian state, to no avail, and was convicted for the debts he had run up with the colonial venture. In March 1847, posters across Brussels announced the seizure of all of his properties and assets – including his family’s collection of arms, which were even exhibited at the newly-opened Porte de Hal Museum. He was arrested again in Paris and died a ruined man in Clichy prison for debtors in 1853.

Monument in the Belgian cemetery in Santo Tomas today

As the years went on, Brussels pushed the colony out of sight and out of mind. It eventually dealt its coup de grace by pulling all financial support – a final betrayal for the few that remained. In 1854, official colonisation efforts in Santo Tomás ceased altogether. In July of that year, the Guatemalan government revoked the concessions made to the Belgian Colonisation Company, saying they had not fulfilled their part of the agreement. In the decree, they decried “damage to the republic” and condemned the precarious state of the colony declaring that it needed to be stopped before it unleashed “irreparable evils”.

Many settlers moved back to Belgium on repatriation ships sent by the state. By 1858, only 40 Belgians remained integrated with the local population. A Belgian-descended community survived, with many descendants in the area carrying Belgian names: Esmenhaud, Vandestadt, Aerens, Vanderberghe and Guise.

There are testaments of the Belgian colony in the city of today, known as Puerto Barrios, including a Belgian cemetery, which one person recently reviewed online as being “full of garbage, neglected and falling apart.” A documentary on the colony by Belgian filmmakers An van Dienderen and Didier Volckaert, Tu ne verras pas Verapaz, includes the story of the Belgian descendants who were denied a Belgian passport, something which they felt was their right not only because they felt Belgian, but also due to the promises their country made to their settler ancestors.

Leopold I would rue the failure of Santo Tomás until his dying day, believing Belgian people were not made for colonisation. Yet Belgian colonialism would rear its head again in the reign of his infamous son. Leopold II was said to have learnt from the “mistakes” of his father at Santo Tomás as he seized control of Congo, exploiting it brutally. When asked about it, Leopold II said: “A Santo Tomás based on emigration could never succeed. The Belgian does not emigrate.”