The people of the city of Brussels put up with three centuries of chronic digestive complaints including dysentery, according to research carried out in latrines in use from the 14th to 17th centuries.

The research, by the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences (RBINS) in Brussels together with Cambridge University, looked at evidence of parasites found in the three latrines in use during the medieval and early Renaissance periods.

The latrines were situated in the Rue d’Une Personne, which runs parallel to the Galeries Saint-Hubert and the Rue des Bouchers, a bustling artisan and commercial centre, and two more in the Rue des Chartreux close to Rue Dansaert.

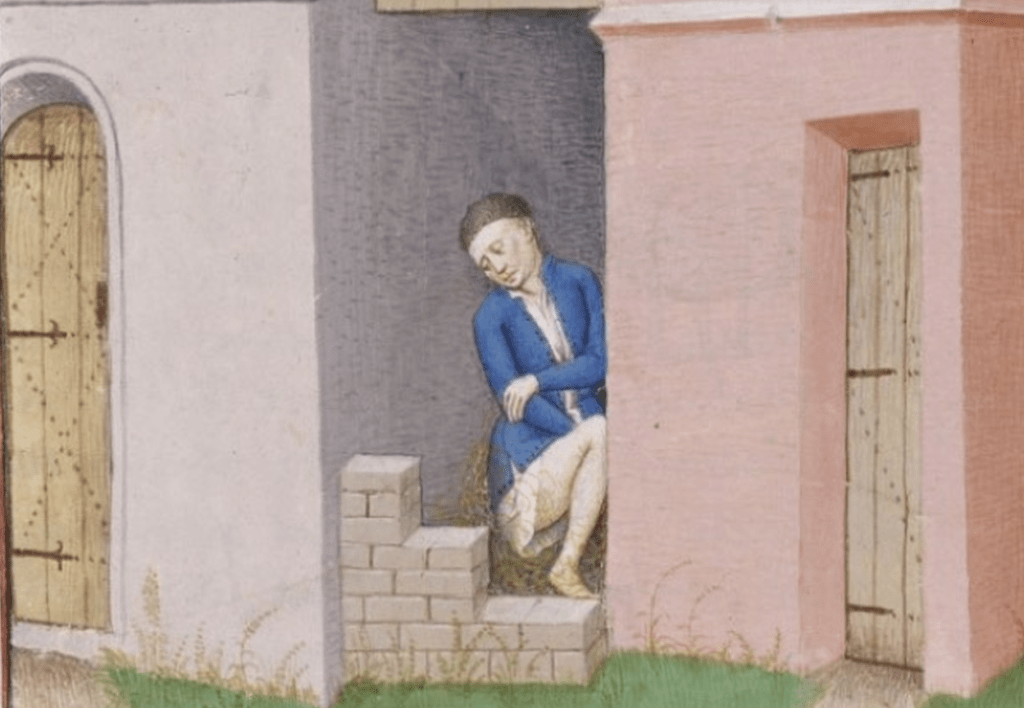

Each of the latrines was used by a whole household and only emptied of its contents when it became too full. The evidence available was contributed by many different people over a long time period. And considering only a well-off household could afford a latrine, the suggestion is that the poor of the city were even more gravely affected.

“While some variation existed between households, there was a broadly consistent pattern with the domination of species spread by faecal contamination of food and drink (whipworm, roundworm and protozoa that cause dysentery),” the paper explains.

“These data allow us to explore diet and hygiene, together with routes for the spread of faecal-oral parasites.”

Among the ways such disease would be spread was the common practice of using ‘night soil’ – as the faecal matter was politely called – as fertiliser for market gardens in and around the city. More was simply dumped in the River Senne which flowed through the city centre.

Much later, in the 19th century, the poet Charles Baudelaire described the river as an open sewer, which indeed it was. Another witness called it “the most nauseating little river in the world”. Soon after, works began to cover it over within the city limits.

As well as traces of the eggs of worms, each of which cause their own complaints, the archaeologists also found evidence of the amoeba Entamoeba histolytica, and the single-celled flaggelate organism Giardia duodenalis – both of which can cause dysentery.

Dysentery is a form of gastroenteritis which is typified by diarrhoea containing blood. Symptoms are fever and abdominal pain, as well as dehydration – which as the water of the city was undrinkable as well as a vector for the disease itself, meant treatment was virtually unheard of.

In addition, the living conditions of the time, and the state of knowledge of hygiene, meant that dysentery would have been more or less endemic during the whole period.

“Old latrines are a treasure trove,” commented Koen Deforce, archaeologist with the Institute and co-author of the study.

“The remains of plants and animals that were eaten but not completely digested, such as kernels and other seeds, small bones and fish bones, can often still be identified,” he said. “They provide us with information about the diet and nutritional patterns of earlier populations.”

And the Senne itself was in large part to blame.

“The Senne functioned as a sewer until the 20th century, regularly flooding the lower-lying areas of the medieval and post-medieval city. This allowed infectious diseases to spread easily,” he said.

The study is published in the latest edition of the journal Parasitology.

Alan Hope

The Brussels Times