Our society might be better off with politicians who have fewer convictions, less principles and less beliefs.

This might seem a bold, rather counter-intuitive statement. To be a person of principles, to be willing to defend ones beliefs, to have clear convictions about the way we should be heading; these are all characteristics we tend to associate with a noble, praiseworthy, virtuous character.

People who lack convictions, beliefs, and principles often lack a moral backbone. So why should such a questionable character trait be what Belgian politicians need?

Before I try to answer that question, I need to include a disclaimer: I began writing this piece exactly a year ago. It was three months after the elections, and a federal government was still nowhere in sight. I tried to commit a few ideas to paper – the core of the column you are about to read – about why the government formation in Belgium is such a slow and difficult process.

Then these ideas ended up in a drawer of my desk, among all those other things to finish. But we are now one year and three months after the elections, a federal government has still not been formed, and after I recently saw a programme on a Polish news station, I thought it would be good to open that drawer again.

An international tragedy

The programme is entirely devoted to the world news: the important things that happen beyond the Polish borders. It lasts fifteen minutes and regularly consists of three items. The episode I watched dealt with these topics: the protests in Belarus, the aftermath of the terrible explosion in Beirut, and… the ‘headaches of King Philippe of Belgium’.

It was quite troubling to see: the episode went straight from the rubbles and ruins of Beirut to the royal castle in Laeken, images of Bart De Wever and Paul Magnette standing next to the king, followed by a live-broadcast from a correspondent in Brussels, as if going from one international tragedy to another.

After more than a year and 3 months since Belgian general elections were held, the country is yet to form a federal government © Belga

Maybe that is what Belgium has become, maybe that is how the world looks at us: a tragedy on the stage of world politics. To be a news item is rarely a good thing, for the news is dominated by the bigger and smaller disasters of the day. Being an international news item is often a terrible thing.

Here in Belgium we’re getting used to having to do without a proper federal government, so you could almost forget how unusual that is.

In 2010-2011 the formation took 541 days. Now we are getting close to beating that record. So perhaps it is good to delve into the question I asked myself a year ago: why is this formation such a painful process, and why could we be better off with fewer principles and convictions in the political arena?

Max Weber’s distinction

A possible answer comes from Max Weber, arguably the most important German sociologist of the previous century. In 1919, he wrote a small essay, Politics as a Vocation. In it, Weber analyses the main characteristics of the life of politics, the motivation, mind-set and capabilities that are required to be a good politician. Weber made an important distinction that is as relevant today as it was back then.

He claims there are two kinds of politicians, characterized by two opposite mind-sets. There are those who participate in politics because of their principled convictions. And there are those who do politics out of a sense of responsibility.

(A third category would be those authoritarian politicians who have neither convictions nor a sense of responsibility but only want to grab power and stay in power).

Weber argues that it is in particular the second category that are conducive to the wellbeing of society: politicians driven by a sense of responsibility. It is out of this sense that these politicians are better able at putting their own egos and ideas aside, when the common good and the wellbeing of society are at stake.

Weber is sceptical about politicians who stick to their beliefs, who shout them into the public domain through a megaphone, who expound them with clenched fists, who turn their opinions into sacrosanct dogmas that are non-negotiable and can’t be discussed. They make the essence of politics impossible.

Clenched fists and open hands

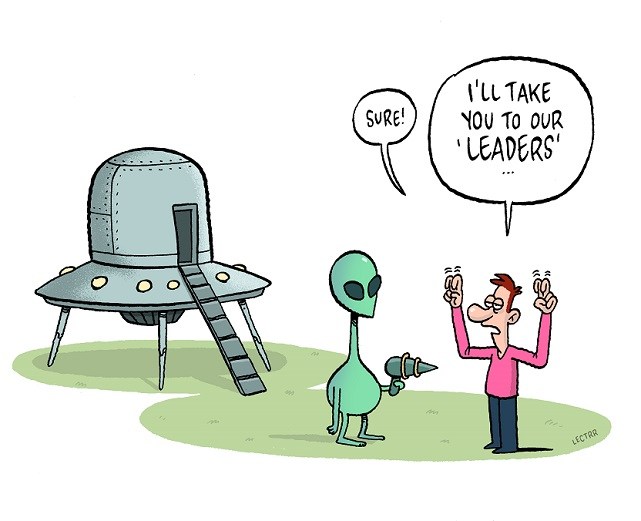

Politics is all about being able to negotiate, trying to find consensus and reaching compromises. The public debate should be a dialogue, not a duel, in which your speech is not a clenched fist but an open hand reaching out to the other side.

It is not hard to see how Weber might be right: we are seriously in need of politicians who are driven by a sense of urgency, a sense of responsibility. That applies to our polarized times in particular, when the political climate is dominated by strong statements, catchy quotes and a proliferation of big promises and exalted principles.

Impasse

Prior to and following the May 2019 elections, our political parties made numerous bold statements about the people and parties with whom they were certainly not willing to make a government. They were more vocal about what they definitely didn’t want to do, than about what they wanted to do for this country.

Almost all the Walloon parties have stated that they are as willing to form a governing coalition with N-VA as a cat is willing to jump into water.

The former president of the Flemish socialists declared that Bart De Wever should turn into a climate activist, who agrees with the communist manifesto, before SP.A would consider joining N-VA in a federal government. The Greens have been depicted as semi-communists, who would be willing to adopt the most drastic measures and eradicate the most essential freedoms for the sake of the environment and the fight against climate change. And so on and so forth.

It seems as if each party defends a worldview that is incompatible with another. That is absurd, and it makes formation talks immensely complicated. In politics, when you don’t want to give an inch, no one will get anywhere. Result: impasse. That is where we are now. That is where we have been for hundreds and hundreds of days.

A Wake-Up Call

You can reasonably wonder: if the biggest international health crisis of the post-war era, and its terrible economic and social impact, do not imbue our politicians with a profound sense of responsibility, what will? Is there a wake-up call to which our politicians won’t remain deaf?

This country is as badly in need of a federal government as California is of rain. People cannot hold the weather gods accountable, but they can hold their politicians to account. If we are heading to new elections, the result might be a devastating blow to the political establishment. Whether this will be to the benefit of the country, and whether it will make the formation of a federal government easier, is far from certain.

What this country needs rather than new elections, or politicians who once again act as the true defenders of the truest of principles, is what any healthy democracy has to rely on: politicians who certainly have ideas and ideals, but whose sense of responsibility is stronger than their belief in the righteousness of their own beliefs.

Alicja Gescinska