Nearly 80 years after the end of the Holocaust, a one-day exhibition co-funded by the EU at the Jewish Museum in Brussels demonstrated how detailed archival research is necessary to uncover the stories of the fate of the millions of objects stolen throughout Europe by Nazi officials, their collaborators and allies.

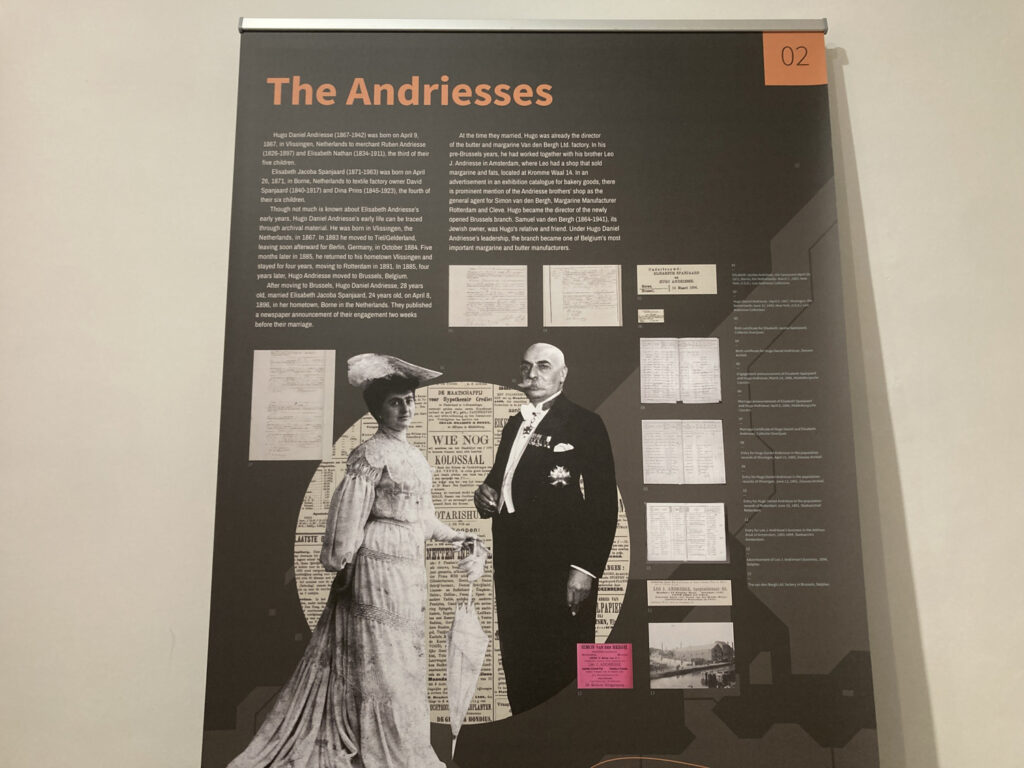

As previously reported, the dramatic story of the looting and partial recovery of a valuable Belgian art and textile collection was recently presented at the museum. The exhibition traced the lives and cultural impact of the philanthropists and art collectors Hugo Daniel Andriesse (1867-1942) and his wife Elisabeth Andriesse (1871-1963).

Despite its closure for general renovations, the museum opened its doors for the one-day presentation during which it was visited by several school classes. There are plans to exhibit it again temporarily at another museum as a tribute to resistance and the contribution of the Belgian – Jewish couple to Europe’s cultural legacy.

“For our museum it was a way to highlight the personal stories of Belgian Jews persecuted during the war and to re-emphasize the importance of preserving our shared cultural heritage,” explained Barbara Cuglietta, director of the museum.

“The exhibition sheds light on stories of Jewish collectors and artists, and the cultural contributions they made to the city and to this country,” said Dr. Georg Häusler, Director for Culture, Creativity and Sport at the European Commission (DG EAC). “But it also goes into the historical complexities and raises awareness of the scale and impact of cultural theft. This project holds educational potential.”

Hugo Daniel and Elisabeth Andriesse, originally from the Netherlands, lived in a three-storey house built in 1910 at Avenue des Klauwaerts 24, Ixelles. From what is known today of their looted collection, the interior was richly decorated with Old Master paintings, Oriental rugs, and wall tapestries.

The couple was known for their charity. Hugo Andriesse held several honorary positions and memberships. He was the president of the Dutch Society of Charity in Brussels, Member of the Queen Elisabeth Egyptological Foundation, and an honorary member of the Jewish Congregation of Vlissingen, his hometown.

They supported the staff of the factory he managed as well as providing funds for ill and impoverished Dutch residents living in Belgium. They established several foundations to empower young people to study at universities. Hugo Andriesse also made a donation to a newly built synagogue in his hometown Vlissingen.

Their happy life in Brussels would come to an end with the Nazi occupation of Belgium in 1940 and they had to leave everything behind them. The couple managed to flee to New York where Hugo passed away in 1942. At least 127 members of the Andriesse family perished in the Holocaust.

The Andriesse house in Ixelles.

Two looted objects

Elisabeth Andriesse returned to Brussels in 1946 where she found some items of their art collection but most of it had been looted.

“It was easy for the Nazis to rob, stripping people of everything they owned,” said Baroness Regina Suchowolski-Sluszny, a survivor of the Holocaust who was hidden as a child in Brussels. Today she co-chairs the Forum of Jewish Organisations. “Sadly, the people from whom these valuables were taken are no longer with us. But their descendants have a right to reclaim what was lost.”

The Andriesse couple had entrusted their art and textile collection in December 1939 to the Royal Museum of Art and History at Cinquantenaire Park in Brussels. One of the objects was the tapestry Winter, a Brussels tapestry from the 18th century characterized by the two-headed figure Janus.

On her return to Brussels, the museum informed her that the tapestry had been recovered and was being kept safely in the museum. Elisabeth donated the tapestry to the museum as well as a sum of money for needy staff members. She asked the museum to put a label text that she had donated it in memory of her husband. Today it is still in storage and cannot be exhibited because of its bad shape.

Everything that Hugo and Elisabeth had left in Brussels was lost. Their house was occupied by the German occupation authorities. Their chauffeur informed the Nazis about their belongings. Their art and textile collection were looted from the museum and transferred to the Nazi headquarters in Paris from where it ended up in the hands of high-ranking Nazi war criminals such as Hermann Göring.

The only object at the exhibition was the novel Armoede (poverty) by Dutch writer Ina Boudier-Bakker. The book had belonged to Elisabeth’s personal library. It was returned to Belgium after more than 50 years and has been stored at the Belgian agency FPS Economy, which intends to restitute the book to the rightful heirs of Elisabeth Andriesse. The heirs plan to donate the book to the Jewish Museum.

The book Armoede (poverty) by Dutch writer Ina Boudier-Bakker had belonged to Elisabeth’ Andriesse’s personal library and was the center piece at the exhibition, credit: JDCRP

Searchable database

“Archival documentation used for the exhibition made it possible to uncover the details of the looting and the subsequent journey and whereabouts of the objects,” said exhibition curator Anne Uhrlandt at the Jewish Digital Cultural Recovery Project Foundation (JDCRP). “We now know who seized the collection, where it was taken, and what happened to the owners and much of their collection.”

Experts estimate that hundreds of thousands of objects remain missing since the Holocaust. Founded in Berlin in 2019, the JDCRP is constructing a central digital archival repository to facilitate research for these objects. The platform will link documentation from dozens of archives worldwide, allowing the matching of relevant documents and searches for information at an individual document level.

The digital database is expected to become readable and cross-searchable in Spring 2025, using the latest IT tools. JDCRP described it as a pan-European endeavor to restore both the objects and memory of them. What makes it innovative is that it gathers information from the original archives of looting that are scattered around the world and will show what was taken, from whom and when.

“State collections are reluctant to return stolen art,” said Deidre Berger, Chair of the JDCRP Executive Board. “We don’t know the true dimensions of all stolen art but our register could lead to some restitutions if we are lucky.“

“When I perish, do not allow my pictures to die with me. Show them to the people.” Felix Nussbaum (1904 – 1944) was a Jewish-German painter who lived in exile in Brussels until he was caught by the Nazis and deported to his death in Auschwitz. “The Refugee”, 1939, Credit: Felix-Nussbaum-Haus Osnabrück, Irmgard und Hubert Schlenke, Ochtrup © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2014

EU’s position

Georg Häusler, the Commission director, said that it is important to know about a past that we are not so proud of. It is important to fight cultural theft and referred to the actions taken today to prevent the theft of Ukraine’s cultural heritage by Russia.

He told The Brussels Times that the Commission has launched a dialogue with the art market in the context of the EU Action Plan against trafficking in cultural goods. The dialogue aims at sharing information with art market stakeholders on applicable legislation as well as non-legislative measures to prevent and detect trafficking in cultural goods and related challenges.

DG EAC has set up a sub-group reporting to the Commission expert group ‘Cultural Heritage Forum’. The group has already met three times and will continue meeting in the course of 2025. On the prevention side, a regulation (2019/880) provides for a system of import licenses for the most endangered cultural goods and importer statements for other categories of cultural goods.

Furthermore, the 14th sanctions package against Russia includes measures to counter trafficking of cultural property, specifically to protect Ukrainian heritage. As regards the Washington Conference Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art, the EU supports them but is not a signatory to them as they were endorsed by states.

The EU has no legal competence to act with regard to claims for the restitution of particular cultural heritage goods apart from those falling under a directive (2014/60/EU) on the return of cultural objects that were unlawfully removed from one Member State to another one as of January 1963.

Then there is the issue of the return of art objects and archaeological artifacts that are not part of Europe’s cultural heritage because they were looted from the colonies. This is a matter of bilateral relations between countries and lies within the sphere of the competence the EU Member States. The Commission welcomes the return and restitution of cultural property to their countries of origin.

“The EU is a proud co-founder of the JDCRP project given its relevance in protecting and promoting cultural heritage in the context of remembrance, education and cultural policy as well as its strong pan-European dimension,” Georg Häusler concluded. “We hope that JDCRP is able to create a database that is accessible to experts and researchers, and raises awareness of the issue to the public.”

M. Apelblat

The Brussels Times