Peter Paul Rubens, the Flemish master whose brushstroke seemed to channel the very pulse of the Baroque, was more than just a painter of voluptuous forms and vibrant tapestries of myth. He was a diplomat, scholar and the consummate humanist, his life a vivid canvas where art and politics merged.

From his ‘Rubenshuis’ base in Antwerp – part of which has just reopened to the public following a €19 million makeover – the prolific Flemish master produced around 10,000 works of art in the first half of the 17th century, from monumental biblical and mythological masterpieces to exquisitely detailed portraits and lush landscapes.

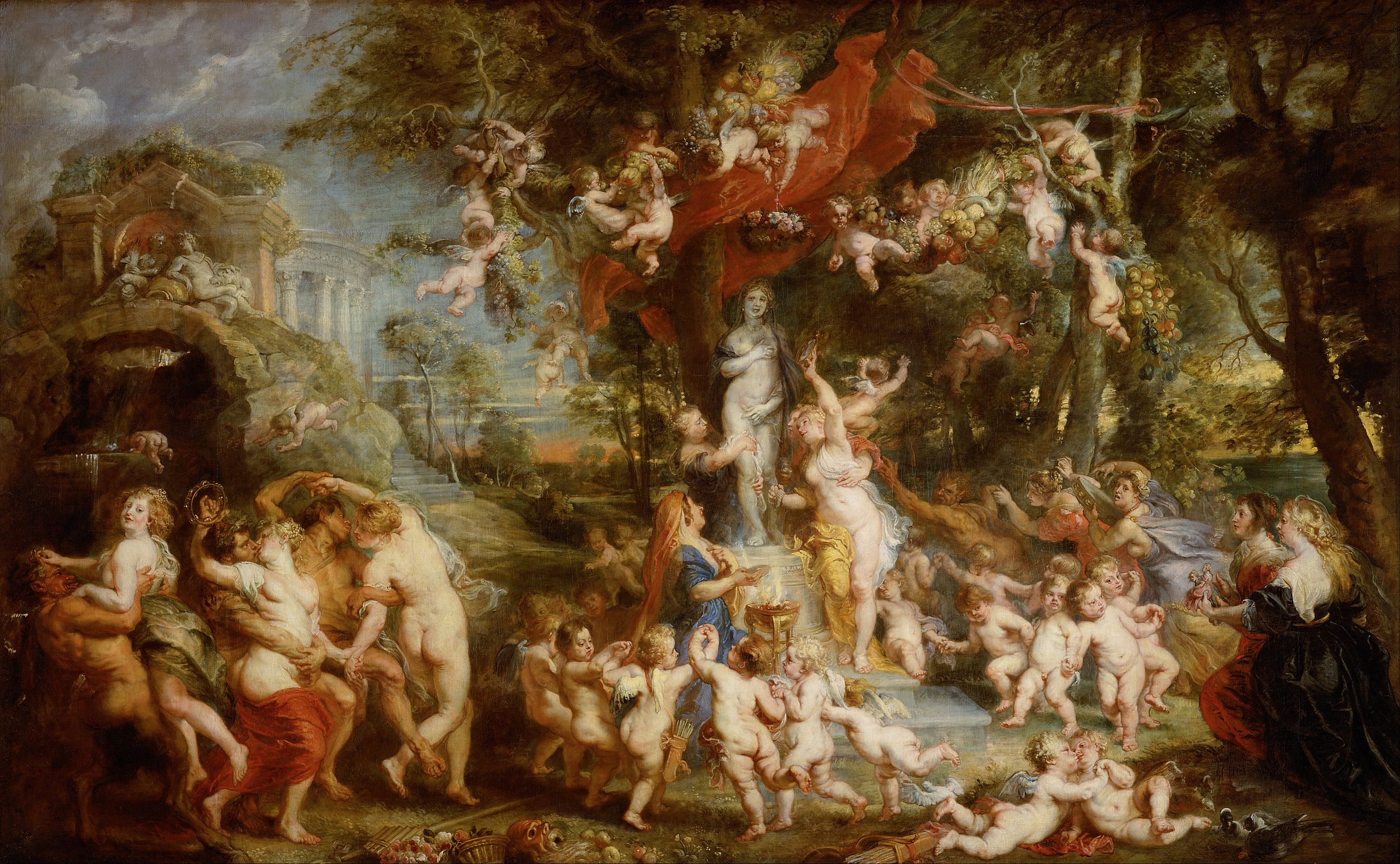

He is perhaps best known, however, for his voluptuous, big-bottomed female nudes, which are the origin of the term ‘Rubenesque’. The artist also depicted male nudes, but they tended to keep more of their kit on.

Early days

So who was Rubens exactly?

He was born on June 8, 1577, in Siegen in what is now the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia. His Calvinist parents, Jan and Maria, had fled from Antwerp nine years earlier with his four older brothers and sisters to escape religious persecution. Catholics were on the warpath after the ‘iconoclastic fury’ which saw Protestant gangs destroying religious icons which, for them, represented avaricious ‘idolatry’.

The Rubens family settled in Cologne but, before long, there was turmoil on the home front, too, when Jan, a lawyer, was caught giving more than legal advice to Anna of Saxony, wife of William I of Orange. The affair resulted in a daughter and Jan was thrown into jail, facing execution.

Self portrait of Rubens, Rubenshuis.

Happily for art lovers (and himself), Jan kept his head and was later freed, returning to an apparently forgiving Maria, who bore him two more boys, Philip and Peter Paul. Times were tough, though: under the terms of his release, Jan was banned from travel and practising his profession. He died when Peter Paul was 10. Maria converted to Catholicism and returned to Antwerp.

Schooled in Latin and Greek, the young Rubens started working at 13 as a page to Marguerite de Lalaing d’Arenberg, Countess of Ligne, but had his heart set on being a ‘history painter’.

At 14 he began a six-year apprenticeship with three mentors, landscape painter Tobias Verhaecht, Adam van Noort, and most notably, Otto van Veen, who imbued him with a lifelong love of Renaissance art and symbolism. At 21, Rubens could finally call himself a master and joined the Guild of St Luke, which meant he could take on commissions and pupils.

From 1600, Rubens travelled extensively, studying for eight years in Italy where he filled his sketchbooks with drawings inspired by Titian, Michelangelo, Raphael, Leonardo da Vinci and Caravaggio. While their influence was evident in his works, Rubens developed his own, richly coloured, dynamic style.

Holy family with the parrot, by Peter Paul Rubens

His talent was soon recognised, and Rubens received significant early commissions from Vincenzo Gonzaga, Duke of Mantua, the Genoese nobility and the Catholic Church.

Rubens also spent several months in Spain in 1603, as the Duke of Mantua’s envoy to the court of King Philip III in Valladolid. While there, he produced the remarkable Equestrian Portrait of the Duke of Lerma.

Returning to Italy, Rubens lived in Rome with his brother Philip, who was secretary to a cardinal at the time. In summer 1608 the artist learnt his mother was gravely ill and set out for Antwerp. Sadly, Maria died before he could arrive.

Settling in Antwerp

In 1609, Rubens became the official painter to Austrian Archduke Albert VII and his wife, Archduchess Isabella, who jointly ruled the Spanish Netherlands from their court in Brussels – though the artist insisted he worked from Antwerp. In October that year, Rubens, then 32, fell in love and wed 18-year-old Isabella Brant, whose aunt was married to Philip.

Already a man of some means, Rubens bought them a house in Antwerp for 9,000 guilders (about €150,000 today), transforming it into a Genoese-style palazzo and studio. Now known as the Rubenshuis, it provided an elegant home for the couple and their expanding family – Clara-Serena (born 1611), Albert (1614) and Nicholaas (1618), as well as live-in staff.

Rubens found himself flooded with commissions as Flanders enjoyed a period of prosperity following a peace deal between warring Habsburg Spain and the Dutch Republic. The Catholic church was a big spender, keen to replace the many paintings and artefacts wrecked during the ‘fury’.

Cupid on a Dolphin, Royal Museums of Fine Arts by Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640)

Fortunately, Rubens could count on the support of a tip-top team of pupils and assistants, including Anthony van Dyck, who helped keep his order book full and the cash rolling in. Rubens also oversaw the mass publication of prints and book illustrations, for which he held profitable copyrights, while sales of his tapestries and architectural pieces proved a nice earner, too.

In the words of Paul Huvenne, former director of the Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp (KMSKA), the artist was now “a combined entrepreneur and virtuoso”. In short, he had become a brand.

While a quick worker on canvas, Rubens was meticulous in his preparation. He would make detailed drawings on paper or sketches in oil before executing a painting. These drafts are often as coveted today as his finished works.

Altar images

His majestic oil-on-wood altarpieces and triptychs were in particularly high demand after his return from Italy. Antwerp’s Cathedral of Our Lady (Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekathedraal) boasts four alone including The Elevation of the Cross and The Descent from the Cross. The paintings are immense: the former measures 462 x 341cm, and The Descent is almost as large, covering 420 x 320cm.

The two works saw quite an afterlife. The French revolutionary army took them to Paris in 1794, but they were returned after Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo. In 1914 they were pinched again, this time by the Germans. They gave them back after the Armistice.

Descent from the Cross, by Rubens

Rubens’s creative powers endured for nearly four decades. When his main patron Archduke Albert died in 1621, Rubens carried on working for the widowed Archduchess. It is thought she introduced Rubens to Marie de Médicis, the Italian-born former Queen of France, who commissioned him to decorate the Palais du Luxembourg in Paris with paintings celebrating her life with Henry IV.

The Archduchess also regularly dispatched Rubens on diplomatic missions – or spying, as some described his activities – at the royal courts in Paris, London and Madrid. His painting was a perfect (and lucrative) cover.

Double tragedy

In autumn 1623, Rubens was devastated by the loss of his eldest daughter, Clara-Serena. He referred to the tragedy in letters, but the cause of her death is unknown.

In 1624, Rubens moved his family to Laeken for 18 months when a deadly plague struck Antwerp. Thinking the worst was over they returned home, only for the epidemic to claim the life of his beloved wife, then 32. Writing to a friend after Isabella’s death, he said: “She had no capricious moods, and no feminine weakness, but was all goodness and honest.” Heartbroken, Rubens portrayed Isabella in The Assumption of the Virgin, one of his celebrated altarpieces in Antwerp Cathedral. She’s the lady in red.

Assumption of the Virgin, 1626, by Peter Paul Rubens

From 1628-31 Rubens threw himself into his diplomatic work to overcome his grief. He spent time in Britain where he undertook commissions from Charles I, including the roof of the new Banqueting House in London’s Whitehall, although experts believe he left much of the work to his assistants (the building was later the backdrop for the king’s execution after his defeat in the English Civil War).

Second marriage

On December 3, 1630, Rubens, then 53, married Hélène (also known as Helena) Fourment, the 16-year-old daughter of a rich merchant. Said to be the most beautiful woman in Antwerp, she was the model for figures in some of his best-known compositions, including The Three Graces and The Judgement of Paris.

Rubens was evidently proud of Hélène’s attributes, often depicting her naked. The couple had five children in less than a decade: Clara-Johanna (born 1632), Frans (1633), Isabella (1635), Peter-Paul (1637) and Constantia-Albertina (1641, born after her father’s death).

In 1635, Rubens bought a moated castle, the Chateau de Steen, known today as Het Steen or the Rubenskasteel, in the countryside at Elewijt near Vilvoorde. It was supposed to be a summer residence, but Rubens spent increasing time there in his final years, setting up his easel in the fields to capture the still recognisable landscapes and scenes of rural life.

He also continued to receive numerous commissions, notably from Philip IV of Spain. Between 1636 and 1640 Rubens made more than 80 mostly mythological paintings for the king’s hunting lodge and the Alcazar Palace in Madrid.

Rubens suffered from gout, a painful form of arthritis linked to a rich diet and excessive alcohol consumption. It left him unable to paint in the last weeks of his life. He died on May 30, 1640, nine days before his 63rd birthday.

Where to see Rubens in Belgium

While many of Rubens’s paintings and drawings have ended up in galleries and museums worldwide, a significant number can still be found in Belgium – mostly in Flanders and often still in the very places for which they were made.

Antwerp

Cathedral of Our Lady (Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekathedraal): four large triptychs: Elevation of the Cross (1610-11), The Resurrection of Christ (1611-12), slightly hidden in a side chapel, The Descent from the Cross (1611-14) and The Assumption of the Virgin (1626-7). These altarpieces are regarded as some of his greatest works.

De Wonderbare by Rubens

Royal Museum of Fine Arts (Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerpen, KMSKA): home to a wealth of Rubens’s paintings, many commissioned for churches that no longer exist.

- Highlights include two masterpieces, Venus Frigida (1614) and The Adoration of the Magi (1624-5). Based on a classical story, Venus Frigida depicts the near-naked goddess of love and Cupid resisting the attentions of a grinning satyr. The painting highlights Rubens’s exceptional skill at rendering realistic-looking skin. The artist made several versions of the Adoration of the Magi. Originally adorning the high altar in St Michael’s Abbey, this one is up there with the best.

- Most of his paintings at the KMSKA are depictions of biblical stories. Ones to also look out for include Christ on the Straw (‘The Michielsen Triptych’) (1618), The Prodigal Son (1618), The Last Communion of Francis of Assisi (1618-9), Christ on the Cross (‘Le Coup de Lance’) (1619-20), Jan Gaspard Gevartius (1628-31), The Education of Mary (1630), The Arch of the Mint (1635) and The Triumphal Chariot of Kallo (1638).

- The monumental Enthroned Madonna Adored by Saints (1628), which originally decorated the high altar at St Augustine Church in Antwerp’s Kammenstraat, is currently undergoing conservation in the KMSKA’s spectacular Rubens Gallery. Curator Koen Bulckens told me the restorers are removing varnish which is obscuring the colours and re-stretching the canvas. The painting is also being scanned by experts from the University of Antwerp to examine it, layer by layer. The museum has made an excellent series of videos about the restoration.

- Other recently restored paintings at the KMSKA include Holy Family with the Parrot (1614-33) – surely one of the best titles ever – Minerva Overcoming Ignorance (1632-33), and Epitaph of Nicolaas Rockox and his wife Adriana Perez (1613-5). Rockox was a mayor of Antwerp and close friend of the artist, who named one of his sons after him.

Saint Charles Borromeo Church (Sint-Carolus Borromeuskerk): Rubens made paintings and sculptures for the tower, facade, altar, ceiling and two chapels. After an absence of 240 years and several auctions, his altarpiece The Return of the Holy Family from Egypt (c. 1620) was returned to its original location in 2017. Sadly, 39 ceiling paintings created by Rubens and Anthony Van Dyck were lost in a fire caused by a lightning strike in 1718.

Saint Paul’s Church (Sint-Pauluskerk): contains Disputation of the Holy Sacrament (c.1609), as well as paintings by Van Dyck and Jacob Jordaens.

- Museum Plantin-Moretus: a former printing press and residence of the wealthy Plantin and Moretus family, includes several portraits commissioned by Balthasar I Moretus, a childhood friend of Rubens.

- Another take on Madonna and the Saints normally hangs in Antwerp’s St James’ Church (Sint-Jacobskerk), where Rubens and his family are interred. The Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage (Institut royal du Patrimoine artistique) is restoring the painting. The Rubens Chapel, behind the high altar, is currently sealed off for renovation work. It is due to finish by the end of next year.

- Four Rubens paintings usually found in St Martin’s Church (Sint-Martinuskerk) in Aalst, including its altarpiece, Saint Roch Interceding for the Plague-Stricken, are also undergoing restoration at the Institute. The influence of Tintoretto and Raphael is evident in this work, commissioned by hop and grain merchants.

- Rubenshuis: Includes a rare self-portrait, on display in the new Rubens Experience room. Other works have been temporarily loaned out or stored while the artist’s residence is refurbished.

Brussels

Oldmasters Museum: Founded in 1801 by Napoleon and part of the Royal Museums of Fine Arts (Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts), it has some 50 paintings and sketches by Rubens and his workshop.

Four Studies of a Head of a Moor by Peter Paul Rubens.

- The undoubted highlight is Four Studies of a Head of a Moor (1614-6), a sketch depicting a man’s head from different angles. The said head reappears in several Rubens works including Adoration of the Magi. Experts were once divided on whether the painting should be attributed to Van Dyck but studies into the layering technique support the view that it is a Rubens original. The title was another source of controversy, with some suggesting that “Moor” is racist or pejorative. Senior curator Joost Van der Auwera has rejected that, insisting: “Rubens wanted to honour the first Christians in Africa.”

- Other notable exhibits include a series commissioned by Cardinal-Infante Ferdinand, the younger brother of Philip IV who succeeded Archduchess Isabella as Governor of the Spanish Netherlands. Executed in 1636, the paintings include Jason and the Golden Fleece, The Fall of Icarus, Death of Semele and Cupid Riding a Dolphin. Larger versions of The Rape of Hippodamia and The Birth of the Milky Way, in which goddess Hera’s face is modelled on Hélène Fourment, are in Madrid’s Museo del Prado. Rubens’s penchant for realism is evident in Portrait of Paracelsus (1615-20) which depicts the Swiss alchemist with a drooping face and double chin.

- The museum will feature sketches by the artist and other iconic painters in a new exhibition entitled ‘Drafts, from Rubens to Khnopff’. Running from October 11 to February 16, it will focus on the creative process.

Église Notre-Dame de la Chapelle: from 1616, Rubens executed several works with sculptor Hans van Mildert including the high altar. Rubens also painted Christ Giving the Keys to Saint Peter (1612-4) to decorate the tomb of fellow artist and friend Jan Brueghel the Elder. The version on view today is a copy. The original was sold in 1765 and is now in Berlin’s Gemäldegalerie museum.

Ghent

Saint Bavo's Cathedral (Sint-Baafskathedraal, Sint-Baafsplein 1): The Conversion of Saint Bavo (1624) altarpiece features the Roman solider who, having quit the army to join the Church, is received as a monk by Saints Amand and Floribert.

Museum of Fine Arts (Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Fernand Scribedreef 1): Belgium’s oldest museum has one of several versions of Saint Francis of Assisi Receiving the Stigmata (c. 1633), an altarpiece for a church that no longer exists.

Portrait of a man as the god of Mars, by Rubens. Credit: Eric Lalmand/Belga.

Mechelen

Church of Our Lady over the River Dijle (Onze-Lieve-Vrouw-over-de-Dijlekerk, Onze-Lieve-Vrouwestraat): contains The Miraculous Draught of Fishes (1619), commissioned by fishmongers envious that another local church (see next item) already had a Rubens. In 1794, the triptych was moved to the Louvre during the French occupation. The upper part was returned after Napoleon’s defeat but two paintings which formed the lower ‘predella’ part ended up at the Musée Lorrain in Nancy and another was given to the Russian Tsar by Napoleon’s wife Joséphine. Conservation experts have spent the past three years restoring the triptych, moving it from the southern to the northern aisle to avoid over-exposure to sunlight. The painting had a lucky escape in the summer when a window behind it was damaged during a hailstorm.

St John’s Church (Sint-Janskerk, Sint-Janskerkhof): another splendid version of The Adoration of the Magi (1617) in which Rubens’s first wife Isabella is said to be the model for the Virgin Mary and two boys are based on their sons Albert and Nicholaas.

The Rape of Hippodame (1636-1638), by Peter Paul Rubens

Best of Rubens elsewhere

- Equestrian Portrait of the Duke of Lerma (1603, Museo del Prado, Madrid). Embodies the power and prestige of the subject, a Spanish military commander and royal favourite.

- Honeysuckle Bower (1609, Alte Pinakothek, Munich). A self-portrait with his first wife Isabella, in the garden of her childhood home on Antwerp’s Kloosterstraat.

- The Adoration of the Magi (1609, King's College Chapel, Cambridge). A favourite theme, this version was an altarpiece in Leuven, sold after the 1780 suppression of convents by Holy Roman Emperor Joseph II. It was later owned by Britain’s richest man Hugh Grosvenor, Duke of Westminster, and bought in 1959 by property millionaire Alfred Allnatt, who gifted it to King’s College. In 1974 the painting was vandalised by supporters of the Irish Republican Army.

- Samson and Delilah (1609-10, National Gallery, London). Bribed by the Philistines, temptress Delilah betrays Samson as he sleeps.

- The Massacre of the Innocents (1611-12, Art Gallery of Ontario). Depicts the Biblical tale of Roman soldiers slaying baby boys on the orders of King Herod. In 2002, Canadian newspaper tycoon Kenneth Thomson bought it for $76.6 million (€70m). A later version of the painting is in the Alte Pinakothek, Munich.

- Lot and His Daughters (1613-14, Private Collection, on loan to The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York). Fetched £44.8 million (€52.5m) at a Christie’s sale in July 2016, over double its estimate. Holy Roman Emperor Joseph I and John Churchill, Duke of Marlborough, were previous owners.

- The Hippopotamus and Crocodile Hunt (c. 1616, Alte Pinakothek, Munich). Dramatic hunting scene commissioned by Maximilian I, Elector of Bavaria.

- Old Woman and Boy with Candles (1616-1617, Mauritshuis, The Hague). A Caravaggioesque painting characterised by its exciting effects of light and unpolished naturalism.

- The Rape of the Daughters of Leucippus (1618, Alte Pinakothek, Munich). Portrays a Greek myth, the abduction of Hilaera and Phoebe by Castor and Pollux. Like many of Rubens’s works it would not pass the #MeToo test today.

- Portrait of a Man as the God Mars (1620, Private Collection). A blend of portrait, allegory and mythology, Rubens depicts the figure wearing a dolphin-headed helmet he owned himself. Sold for $26 million (€24m) at a New York auction in May 2023.

- The Disembarkation at Marseilles (1622-5, Musée du Louvre, Paris). One of 24 paintings commissioned by Marie de Medici, this depicts her arrival in her adopted country, escorted by Poseidon, Triton and voluptuous friends.

- The Rubens Ceiling (1629-35, Banqueting House, London). Rubens’s only surviving in-situ ceiling work, commissioned by Charles I as a tribute to his father and the Stuart dynasty. The Union of the Crowns, The Apotheosis of James I and The Peaceful Reign of James I were painted in Antwerp and shipped to London.

- The Three Graces (1630-5, Museo del Prado, Madrid). Not his first version, but the best known. Rubens depicts the three deities, daughters of Zeus and Hera, who signify beauty, charm and grace. The figure on the left resembles Hélène.

- The Judgement of Paris (1632-5, National Gallery, London). Based on the Greek myth in which Paris must decide who is the most beautiful goddess, Hera, Athena or Aphrodite. He can’t choose while they are dressed and asks them to strip off. Hélène is the model for Aphrodite (Venus).

- An Autumn Landscape with a View of Het Steen in the Early Morning (1635, National Gallery, London). Pastoral scene depicting Rubens’s estate in Elewijt. Influenced John Constable.

- Saturn (1636, Museo del Prado, Madrid). Commissioned by Philip IV, this shocking image depicts Saturn devouring his own sons.

- Perseus Freeing Andromeda (1638, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin). The Greek myth in which Andromeda is shackled, awaiting her sacrifice to a sea monster.

- Consequences of War (1639, Palazzo Pitti, Florence). Also known as the Horrors of War and thought to symbolise the Thirty Years’ War. A voluptuous Venus, Goddess of Love, strives to restrain Mars, God of War.