Art Deco is set to dominate Brussels's cultural agenda in 2025. This year marks the centenary of the first Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels, held in Paris from April to October 1925, which brought together designs from 20 participating countries. Most built a show pavilion by a star architect (Belgium chose Victor Horta), but all sent the latest creations of selected artists, and historical references were prohibited to encourage innovation.

Art Deco as a term was only coined in the 1960s but is a welcome contraction of that mouthful of an event. Its centenary marks the international cross-pollination of the ideas that brought about this elusive interwar style, often interpreted as a transition between Art Nouveau and modernism.

An umbrella term applied to a wide swathe of the visual arts from around the interwar period, Art Deco’s global avatars are skyscrapers, such as the Empire State and Chrysler buildings in New York City. In Belgium, their exact contemporary in Antwerp, the Boerentoren was once the second tallest building in Europe.

In the wake of last year’s Art Nouveau Year, the Brussels Region has declared 2025 Art Deco Year and dozens of exhibitions and events will explore the theme in depth. Beyond the coffee-table draw of the major architectural heritage, Art Deco was arguably the first art movement to penetrate daily life at virtually every level of society from luxury creations to the packaging of humble consumer goods.

Art for the many

Underlining this view is the Boghossian Foundation’s exhibition, Echoes of Art Deco (an excellent title for a term that is evocative rather than self-explanatory). The foundation’s home, the spectacular Villa Empain, was built in 1930 by Michel Polak for Baron Louis Empain, son of self-made railway tycoon Edouard Empain who built the Paris Metro and created a new town, Heliopolis, on the desert fringes of Cairo, connected to the city by his tram network.

The house is perhaps the last word in Belgian Art Deco luxury, clad with polished Italian granite anchored by bronze staples. A fabulous wrought-iron door beneath a deep, flat brass canopy leads into a vast, square, marble-lined and galleried hall with a view through to the garden and a vast outdoor swimming pool, its perimeter traced by a shaded pergola promenade.

Villa Empain when new

The exhibition, on until May 25, takes an immersive rather than documentary approach to its theme, demonstrating the artistic breadth and societal depth of Art Deco. A “journey into the past” is provided through four dimly lit rooms decorated in reproduction wallpaper and dotted with exhibit cases and furniture, blurring the lines between museum and cosseted domestic interior from Les Années Folles (the Roaring Twenties).

Luxury Art Deco is represented by short, slender silk dresses and curved furniture in precious woods, printed or inlaid with abstract geometric and stylised floral designs. The contrast with the bulky dresses and hulking historicist furniture of the previous generation represents the revolution in the public and private image and aspirations of the prosperous classes, particularly women.

Villa Empain today

The star attraction is perhaps the collection of stained glass, demonstrating the timeline of the art over a quarter century through 25 fragments. These show how the figurative themes of fanlights of the late 19th century – such as saints, flowers and animals – had given way, initially to simple, symmetrical, geometric patterns under the influence of the Amsterdam School. With the advent of opalescent coloured glass, designers could track trends in painting: cubism, constructivism, and futurism in the early 1920s, the primary-colour rectangles of De Stijl in the early 1930s and then the curved knots distinctive of late Art Deco from mid-decade.

The exhibition also features a 1923 abstract wallpaper design by Victor Servranckx, which further explores the pan-media nature of this movement in art. In 1925, when he briefly turned to architecture, the artist reproduced identical curved lines across the facade of a building in Anderlecht. These flats, stacked above shops and a café in a modest quarter of the city, reflect the other side of the exhibition: Art Deco as a pan-societal phenomenon.

Villa Empain

Post-war aspirations

Bringing high-quality, modern design within the reach of the many had long been an aspiration for certain artists, in reaction to the poor quality and reactionary taste of early manufactured reproductions. Earlier attempts, through the arts and crafts movement in Britain and Art Nouveau in Belgium, had failed to penetrate much beyond a moneyed few due to the cost of materials and labour.

Over four years, the urgency of war output had improved cost and quality controls, and peacetime supply chains could turn to labour-saving devices and leisure products. The Echoes of Art Deco exhibition illustrates this through a series of posters by graphic designer Hubert Dupont (who signed his output Hub Dup), advertising goods from household appliances to beer using the same design language as the luxury goods elsewhere in the exhibition.

A bank of early radios decked in veneer ape the form and finish of the expensive sideboards. A scratchy soundtrack of period hits completes the immersive effect of the exhibition, and some of the darker numbers, such as Putting on the Ritz and Minnie the Moocher give a glimpse of the psychological cravings behind the glamour of Art Deco. World War (with a cruel occupation in the case of Belgium) followed by the Spanish Flu pandemic had produced a generation at least as traumatised as it was aspirational and in need of distraction.

Upcoming exhibitions will further explore the wider theme of Art Deco, with themes such as cinema, fashion, and sculpture on the programme (see box), but inevitably, architecture is the star. Hoping for a repeat of Art Nouveau Year, which attracted almost two million visitors, the region’s tourism places BANAD (the annual Brussels Art Nouveau and Art Deco festival) among the flagship events in 2025’s cultural calendar.

Running across three weekends in March, this year’s theme will revolve almost entirely around Art Deco buildings, with lectures, neighbourhood walks and visits to usually inaccessible interiors provided by a large network of museums and associations. At the launch of 2025’s themed year, State Secretary for Urbanism and Heritage Ans Persoons promised “a celebration of Brussels’ unique Art Deco heritage,” headlined by the buildings of star architects Victor Horta, Jean-Baptiste Dewin, Adrien Blomme and, not least, the creator of the Villa Empain, Michel Polak.

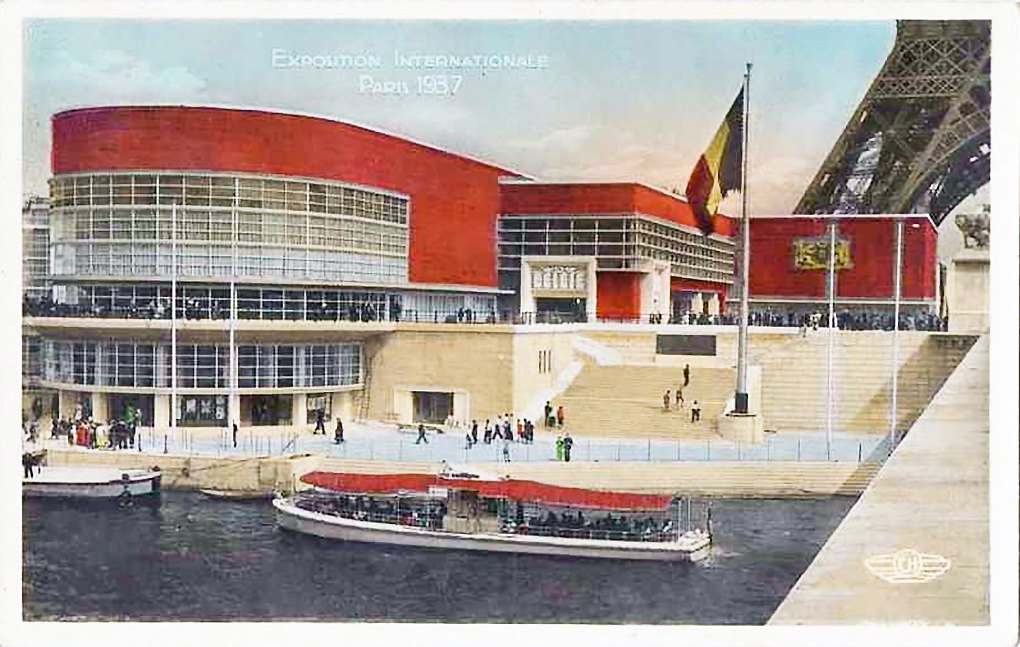

Belgium's pavilion at Expo 37 in Paris

What is Brussels Art Deco?

The decorative tropes of Art Deco architecture are easily recognised. They include geometric motifs inherited from one tradition of Art Nouveau which, amplified across the entire facade of a modest terraced townhouse, create the fun effect that can stop passers-by in their tracks.

Larger buildings (detached mansions, offices, churches, factories) can carry detailing such as exaggerated fluted pilasters and capitals quoting classical architecture, along with winged figures in helmets. Machinery parts such as cogs or fins imitating radiators and heat sinks can underline the modernity of a commercial block or hint at the industrial interests of a mansion’s owner.

A more monumental strand of Art Deco features large expanses of marble, stone or its approximation in concrete, oversized frames for doors or windows which can be horizontal and emphasised by successive layers of moulding. These can reserve decoration for rich ironwork doors with geometric motifs repeated across window guards and gates and railings if a garden is present.

A regionalist variation can feature outsized gables and cornices, combining plaster and brick on the facade to create the effect of monstrous cottages. The 1930s saw a turn towards naval architecture with portholes, flagpoles and terraces with tubular guard rails evoking the paquebot (ocean liner), the ultimate expression of modern moneyed leisure in search of exoticism.

The Belgian twist

But what is Brussels or Belgian Art Deco? The art historians Maurice Culot (founder of the Archives of Modern Architecture, AAM) and Anne-Marie Pirlot locate its “birth certificate” amid the Austrian strand of Art Nouveau known as the Viennese Secession. In particular, the enormous mansion built in 1905-11 for another Belgian engineer-industrialist, Adolphe Stoclet, by Austrian architect Josef Hoffmann whom he had met while building railways in Vienna.

Its restrained exterior clad in vast expanses of white marble, the inside of the Stoclet Palace was entirely fitted out by the Wiener Werkstätte artists collective co-founded by Hoffmann in 1903. Madame Stoclet obediently auctioned off her collection of (no longer) modern art in anticipation of the shimmering mosaic friezes to be created by Gustav Klimt (at least, they appear to shimmer in photographs; barely anyone has been permitted entry to the Unesco World Heritage sphinx, and the Brussels Region has gone to court to contest this).

Stoclet Palace. Credit: Belga / Herwig Vergult

This Stoclet style reached a wider, if still extremely wealthy, public thanks to L’Intérieur (The Interior), a shop and gallery opened by architect Léon Sneyers in 1907 which stocked the Vienna collective’s products. Sneyers was a former student of Paul Hankar, a pioneer of Belgian geometric Art Nouveau who began work on a house inspired by Japanese art at the same time as, a couple of blocks away, Victor Horta was creating the Hôtel Tassel, the first building in the organic, floral branch of Art Nouveau. Sneyers encountered the output of the Secession at the First International Exposition of Modern Decorative Arts of 1902 in Turin. A 1904 shop front by him at number 7 Rue de La Madeleine features curves and stylised stained-glass flowers, motifs that would seed the basic elements of the more decorative tendency in Belgian Art Deco.

The Brussels Region’s heritage inventory briefly defines Art Deco as an “interwar” style favouring the “geometrization of forms and ornamentation.” It lists 1,899 examples in its database of sites worthy of attention (compared to 1,196 for Art Nouveau). Modernism meanwhile (with just 899 mentions) is “an international trend calling for the primacy of function over form…characterised by the use of elementary geometric volumes, flat roofs, panoramic windows and modern materials such as reinforced concrete.”

Confusingly, this definition seems to match Blomme’s Wiels centre from 1930 and is illustrated with an image of the Kaaitheater, which the inventory lists as “a modernist and Art Deco ensemble in the Paquebot style”. In a wordier entry, the inventory for the Flemish region defines modernism as “a striving for renewal” and a “business-like” appearance with “most buildings” falling short of this ideal of “purity”.

Dressing-up box or hairshirt?

The plastic possibilities of modern construction techniques (metal frames and reinforced concrete) and the end of the classical/renaissance stranglehold on official architecture and its teaching left architects able to reproduce and blend exotic styles from all periods. A sort of dressing-up box of history. Leaving modernists to question whether they should.

In this light, it is perhaps best to regard Art Deco as sitting on a spectrum of modernism that depends on its perceived seriousness in the eyes of the individual critic (depending on mood). In short, it can be both things at once, a curate’s egg of a style. The Flagey Building, for example, has long stretches of modernism, with bands of windows set in a flat, restrained facade beneath a flat roof but spoils the hairshirt ideal with the helter-skelter corner tower that makes it so memorable. The inventory describes the Villa Empain meanwhile, that avatar of Brussels Art Deco, as a “modernist update of the classical ideal in architecture.”

A commercial block in Anderlecht, designed by Victor Servranckx in 1925

Sneyers’s profile in the AAM architecture archive (now part of the CIVA architecture and urbanism museum in Ixelles) compares him to Joseph Urban, another architect (Austrian this time) with a side hustle in selling Secession products. His New York City shop called the Wiener Werkstätte was a commercial failure but a heavy influence on the American strand of Art Deco that weighs so heavily on global perceptions of the movement. Urban would go on to create stage and film sets and co-designed US Art Deco landmarks such as the Ziegfield Theater in Manhattan (demolished) and the Florida resort of Mar-a-Lago (still in daily use).

As for the more monumental tradition in Belgian Art Deco, this can perhaps be traced back to the designers of the 1913 Théâtre des Champs-Elysées in Paris, one Belgian and the other at least Belgian-born. Built to house avant-garde concerts and ballet productions, its facade was initially developed by Antwerp native Henry Van de Velde, who handed over to Ixelles native Auguste Perret (a plaque in Rue Keyenveld recalls his birth in the street, a few doors down from that of the more box office Audrey Hepburn). The sober and massive travertine facade, mounted on a concrete frame, somewhat prefigures the horizontal monumentality of the Villa Empain.

Where it is in Brussels

Given its timeline of roughly 1919-1939, the footprint of Art Deco in Brussels reflects the needs and opportunities in the region during the interwar years. The main factors in and around the already entirely built-up historic centre of the city were the spaces freed up by major updates of the communications networks and the pressure to modernise the entertainment, hospitality and commercial infrastructure to cater for both visitors and the fortunate section of the region’s population with rising incomes and leisure hours that could be spent in the centre. Meanwhile, universal (male) suffrage had arrived in 1919, meaning the educational and healthcare needs of the dwindling and increasingly impoverished inhabitants of the centre required attention.

Central

In the northwest corner of the so-called Brussels Pentagon, docks rendered obsolete by the moving of the canal and the construction of new warehouses served by rail (now Tour & Taxis) were filled in. Two wide new boulevards were laid out at diagonals within a vast rectangle. The deep plots prompted the construction of warehouses and apartments on a new scale for Brussels, with lifts allowing buildings of a height then associated with US cities. Art Deco detailing abounds in this area but the style had to duke it out with an instinctive preference for more traditional designs with which it would often share facades, as it would across the region.

At 66 Boulevard d'Ypres, the entrance porch to a 1927 apartment block combines Art Deco, beaux arts and Art Nouveau elements in a sumptuous ensemble. To the northeast, the enormous Yser Salient residential block is wrapped in Art Deco marble at street level and the style claims the ironwork on the windows of the beaux-arts facade above. Opposite, across Square Sainctelette is the Kaaitheater, a complex combining a café and theatre with flats above. Their curved balconies with tubular guard rails in the Art Deco Paquebot style contrast with the sober horizontal modernist windows that flank them, thus placing it among many others as being in both styles in the official inventory.

Kaaitheater, Brussels. Credit: Fred Romero

Next door is the former headquarters, workshop and showroom of Citroën Belgium from 1933. Occupying almost the entirety of this enormous city block, it was built over a cavernous and long defunct deepwater dock. Dealing with this has helped delay its conversion into the forthcoming Kanal Museum (and future home to CIVA). The 25-metre-high showroom section is of a functionalist purity to qualify this as a modernist structure. It was designed by Alexis Dumont and Marcel Van Goethem.

On the eastern slopes of the Pentagon is another tight knot of major Art Deco-influenced buildings, filling gaps left at the beginning of the 20th century by demolitions for the north-south railway junction and the construction of Rue Ravenstein, a new access road curving its way to the upper town. Here Dumont and Van Goethem built the Shell building as new modern offices for the oil company in a restrained Art Deco with stylised blue stone uprights between austere bands of white stone cladding. It doesn’t quite make the purity test for modernism and the inventory is silent on its architectural style.

On each side of the former Shell HQ are major late-period buildings by Victor Horta, both included within the universe of Art Deco Year 2025. On a fiendishly difficult site, the Bozar, from 1922-29, fulfilled the need for a new cultural hub in postwar Brussels. Built down rather than up, it had to duck below the parapet of the Rue Royale to preserve sightlines downtown from the Royal Palace, and the vast concert hall shares the street level of the medieval quarter demolished for the new road. The Brussels region’s inventory describes this as a classically inspired building which “announces Art Deco”, and this is particularly evident from its geometric roofline and opulent yet austere interior, lit by opalescent stained glass.

Across Cantersteen is Horta’s Central Station, a 1936 design completed posthumously. It bears “reminiscences of classicism and Art Deco,” the inventory states. While its undulating entrance facade is a clear reference to the architect’s (now demolished) Maison du Peuple, the tall windows lighting the booking hall with their grid of square glazing bars are perhaps a reminiscence of the entrance tower of the Stoclet Palace.

The Henry Le Boeuf Hall in the Brussels Centre for Fine Arts, designed by Victor Horta. Credit: Bozar

In the heart of downtown, Michel Polak built no fewer than three Art Deco hotels along the axis leading along Boulevard Adolphe Max to Place Charles Rogier. The Atlanta from 1925 with curiously exotic missionary baroque touches (Polak was born in Mexico) and the Plaza from 1928 are in the boulevard while the Albert I in the square is from 1927.

Within the outwardly-restrained Plaza complex is the former cinema of the same name, its interior another example of exotic Art Deco, is in a “Hispano-Churrigueresque” style. Behind the Métropole Hotel is the enormous former Métropole cinema from 1931 by Adrien Blomme, working once again for the Wielemans-Cueppens brewing family. The 3,000-seat auditorium behind its monumental travertine facade has long vanished and is now the Rue Neuve branch of Zara.

Just around the corner in Rue du Fossé Aux Loups a casino occupies the former Cameo Cinema from 1925, with an extrovert facade pushing it into the ‘fun’ category of Art Deco. A few steps away again is a 1931 Art Deco auditorium (Marcel Chabot) of the former Eldorado cinema, now concealed behind the glass façade of the UGC De Brouckère. Suspended in a concrete frame, a gilded profusion of Art Deco bas reliefs sat above the velvet banks of seating. Congo-inspired exotic plants and animals (and humans) for the walls, an immense sunbeam for the ceiling at the end of the audience sight line, as if bursting from the screen with promise of the spectacle to come. These cinemas, largely targeting a suburban public visiting town for shopping and entertainment, feature in the Art Deco Cinemas of Brussels exhibition running at the Halles Saint-Géry until May 11, 2025.

Cinema Metropole on Rue Neuve, which today houses a Zara clothes store.

In the oldest parts of downtown Brussels surrounding the Grand Place meanwhile, there was a growing awareness of the attractiveness to tourists of narrow, winding streets lined with quaint-looking houses. To the disappointment of certain modernists who wished to see much of this razed, architects elsewhere engaged in the production of Art Deco, rebuilt ancient facades in pastiche or inserted regionalist-type new buildings aiming at showing sympathy with older neighbours.

The architect De Vleeschouwer, who rebuilt two 17th century houses in Rue Au Beurre, would go on to design the sumptuous Art Deco curves of the 1928 Villa Descamps in Avenue Hamoir in Uccle. On the corner of Rue des Chapeliers and Rue de la Violette, the architect Van Eng inserted a discreet curved Art Deco block above a marble-clad shop, the curvy decorations of its stained glass announcing the 1930s variant of the style. Further up the medieval Rue de la Violette in 1937, Adrien Blomme and son Yvan, the designers of the Midi Station, built the Ecu de France restaurant and jazz club with a brick and plaster regionalist facade. Opposite the Bourse meanwhile, a 1930s update of the Falstaff, an art nouveau German weinstube turned English pub, left much of the spectacular wood and stained glass in place, adding a practical and more glamourous flat Art Deco canopy to shelter drinkers on the terrace.

European Quarter

In the tightly built-up inner suburbs of the 19th century, the traces of Art Deco are sparse. Here, the style found a meagre foothold by replacing a few facades by prosperous, aspirational owners. Those of lesser means contented themselves with a moderne roof extension, a geometrical wrought-iron door or stained-glass fanlight, cheerfully clashing with the existing architecture (my own 1901 home has a streamlined door handle facing the street, incised with a stylised fan motif).

An exception was the aristocratic Leopold (now European) Quarter, where the upper classes were abandoning draughty palaces rendered obsolete by a lack of servants. Providing a “solution to the housing crisis” as Le Soir put it, developer Lucien Kaisin demolished a dozen mansions on Rue de la Loi and brought Polak to Belgium to design Résidence Palace, a 180-apartment mammoth “in the style of the Italian Renaissance with the decoration of our times”. With fully serviced flats of up to 22 rooms aimed at these very rich refugees, the complex boasted a fabulous Art Deco swimming pool in the basement (which survives and is included in the Banad programme) and a rooftop terrace for tea dances beneath a pergola.

In the nearby Leopold Park is another major Polak Art Deco building, this time with a more democratic pedigree. The former dental clinic for children from low-income families was funded by a $1m donation by Kodak founder George Eastman. A reinforced concrete frame clad in white stone, its form, but not decoration, was required to evoke the original dispensary in Rochester, New York. The interior, home since 2017 to the House of European History, was furnished in Congo wood by De Coene Brothers of Kortrijk. A large translucent roof extension added as part of the conversion somewhat blurs the horizontality of the façade, where Art Deco meets modernism.

The former dental clinic for children, which today the House of European History.

The outer suburbs

Garden grabs are nothing new. A little further out, the grounds of larger estates presented opportunities for developers targeting new arrivals and those disenchanted with dowdy, last-century homes. In Schaerbeek, Kaisin aimed the 1929 Pavillons Francais, a gleaming white 15-storey skyscraper heavily influenced by American design, at aspirational middle-class buyers (freshly restored, BANAD is organising visits to the building for the first time in 2025).

The same year, the secluded Square Coghen was laid out in a loop across a sloping patrician estate in Uccle. An open-air laboratory for interwar architecture completed in under a decade, the region’s inventory classes 33 of its houses as modernist, seven as Art Deco and four as regionalist.

On a large vacant corner site on Avenue Brugmann, formerly aristocratic rural land, Empain group transport engineer Robert Haerens commissioned Antoine Courtens to build a large mansion in the Art Deco style. The former pupil of Horta placed a tower resembling the summit of a skyscraper at the right angle between two wings with facades in blocky geometric stone. Inside and out, Courtens’ extensive ironwork features incised circles crammed into geometric frames, evoking machine cogs. Also from 1928, at the Rond-Point de l'Étoile Ixelles, on the fringe of fully built-up Brussels, is Courtens’ Palais de la Folle Chanson, an apartment building which pursues the same form but with added altitude.

Meanwhile, Art Deco row houses appeared in streets laid out before World War One but incomplete or left entirely fallow pending a recovery of the construction industry and demand. Avenue Coghen abounds in examples. At numbers 59 and 61 and opposite at number 68 with its naval-looking roof terrace are examples of what could be termed the fun end of Art Deco, all by Louis Tenaerts and dating from the mid-1930s. Cramming strong vertical and horizontal lines, portholes, cylindrical outcrops and (where it survives) stained glass typical of the Paquebot period (as seen at the Boghossian show) in a confined space, they pull off a pictorial effect.

Illustration picture shows the Art Deco building La Magneto Belge, in Brussels on Sunday 20 August 2023. Credit: Belga / Nicolas Maeterlinck

Around the corner at Avenue de la Seconde Reine 5, is Tenaerts’ masterpiece or greatest indulgence, depending on the extent of one’s allegiance to the modernist ideal of simplicity. A greatest hits of the principal tropes of Art Deco, each amplified to the maximum degree, the Maison Marit from 1933 perhaps left the style with nowhere else to go.

Opposite the Palais de la Folle Chanson, at the entrance to Avenue du Congo are two equally tall apartment buildings by architect Jean-Florian Collin, tracking Art Deco’s journey from experimental and somewhat risky art movement to safe choice for the speculative investor. The 1930 Palais du Congo at number 2-4 is a rather bland echo of Courtens’ pioneering flats at the site. At number 3, the 1936 Résidence Ernestine, for Collin’s own Etrimo development company founded in the meantime, Art Deco has already reached its fully-commodified endpoint. A circular tower, tripartite this time, is embraced between tight fins rising to the full height of the building.

It followed the 1935 Brussels International Exposition, whose public face at Heysel was the Palais des Expositions, its Art Deco façade an enormous, truncated triangle mixing strong horizontal and vertical lines with the soaring glazing of Central Station (and the Palais Stoclet before it, where the story perhaps began).

Revival

Like the Art Nouveau before it, a world war largely ended Art Deco, its frivolous leanings finally eclipsed by the decidedly not-fun strand of modernism.

In their essay on the style in the book Modernism Art Déco (published by the Brussels region in 2004), Culot and Pirlot date Art Deco’s reappraisal to an exhibition held at the Museum of Ixelles in 1968 amid growing dissatisfaction at the functionalist vision taking hold of the city, a vision now synonymous with Brusselization, the destruction of swathes of the cityscape and extraction of the picturesque, the fun.

Shell headquarters in Brussels, a fine example of Art Deco

The two art historians credit that event in Ixelles (billed as Antoine Pompe et l’Effort Moderne) to Art Deco’s revival from the 1980s onwards, via a new generation of postmodernist architects for whom imitation of the interwar style presented less scholarly effort and fewer demands on contractors than reproducing Art Nouveau or classicism. Their star examples are the 1989 SAS Hotel (now Radisson Grand Place) and Espace Midi, vast and unloved office blocks from 1998-2002 imitating golden-age US skyscraper vocabulary in Avenue Fonsny opposite the South Station (both Atelier d’Art Urbain architects). The merits of Art Deco and the desirability of a revival is a debate still underway.

Criticism of Art Deco styles long centred on their superficiality, putting decoration, the plaything of the past, ahead of functionality. A defective form of modernism, weighed down by the long hangover of the 19th century. This round of events in 2025 will perhaps try to put to bed the long hangover of the 20th century, of measuring architectural merit on a scale of form following function, not the least because function is no more a fixed value than form.

Art Deco, modernist or both, these buildings are nearing their eleventh decade in existence and need renovation and imagination if they are to remain with us over the coming decades. Art Deco Year in Brussels is seeking new generations of fans to make this possible, anchoring the city’s heritage within the region’s renewal plans. And having some innocent, superficial fun while doing it.