Easter is celebrated across the world this Sunday, making it a special year. In a rare occurrence, Orthodox Christians will celebrate alongside Catholics and Protestants – as their Easters fall on the same day.

Orthodox Christianity is one of the main branches of the Christian faith. It is followed by millions of people mostly throughout Eastern Europe, including the Balkans, in Caucasus, Africa and the Middle East.

In Belgium, there are an estimated 150,000 Orthodox Christians, according to Metropolitan Athenagoras, the head of the Orthodox Church of Constantinople in the Benelux region. In Brussels alone, there are no less than 18 churches of this faith. Among the worshippers are Ukrainians, Romanians, Bulgarians, Russians, Armenians, Arabs and many others.

Date confusion

Despite celebrating for the same reason – the belief in the resurrection of Jesus – Western Christians usually celebrate Easter on a different day.

Determining the date of Easter is complex: both traditions celebrate it on the first Sunday after the so-called Paschal full moon (the first one after the spring equinox), the day when daytime and nighttime are the closest to being equal.

Western Churches have the date of the equinox as March 21, calculated by the Gregorian calendar, which Europeans use in day-to-day life. Most Orthodox churches currently have the date as March 21 too, but based on the Julian calendar, which is about 13 days behind the Gregorian. As a result, the Orthodox spring equinox falls on April 3 in reality.

This year, the first full moon after the equinox occurred on April 19 for both denominations, meaning that the first Sunday after that would fall on the same day. This is a pretty rare event of cosmic harmony happening roughly every few years.

A very different Easter

How do Orthodox Christians celebrate? Well, forget the usual chocolate eggs, springtime cheer and pastel bunnies – Orthodox Easter is different. While the regional traditions are diverse, many still share surprising commonalities. Overall, it is not as secular and is deeply rooted in rituals, Christian spirituality and even pre-Christian pagan practices. The significance of the festivity is even greater than Christmas.

These eggs are known as Pysanky. Such decoration is a folk craft popular in Ukraine, Poland, Croatia and other countries. Credit: Unsplash

Everything starts long before Easter with the Great Lent, a fasting beginning 40 days before the holy day. It is usually followed only by the most devoted, still somewhat popular among older people. It includes abstention of meat, dairy and even oil.

Unlike in Catholicism or Protestantism, there is a greater focus on the Holy Week as a whole, compared to just Good Friday and Easter Sunday within the Western branches. In Romania and Ukraine, the Thursday is often referred to as 'Clean Thursday', a day to clean your house, body and soul.

During the Holy Week the fasting gets stricter, secular celebrations are discouraged and there is a daily church service. Gossiping, arguing and swearing is avoided, while acts of mercy and charity are encouraged. This is the time to prepare for the Great Sunday.

Easter itself is known as Pascha, derived from the Jewish Passover. Both of the traditions share a deep theological connection. If you have Eastern European friends don’t get surprised if they tell you “Christ is risen” on Sunday. This is a very common Easter greeting.

Some of the most important attributes of Pascha are eggs, commonly painted at home by the people. In Balkan villages, no Easter celebration feels complete without red eggs, symbolising the blood of Jesus. You might even hear someone say: If you don’t have red eggs, it’s not Easter. In Georgia, Bulgaria and some other countries wine plays a crucial role in the celebration due to its prominence in the region.

Cozonac, Paska and Tsorejki — traditional sweet Easter breads from Eastern Europe. Credit: Wikimedia Commons, Unsplash.

Most countries have some type of special sweet bread, often richly decorated. In Greece it’s Tsourejki — it is braided, flavoured with wild cherry seeds and mastic. In Ukraine, it is yeast sweet bread with raisins and frosting on top known as Paska. Romanians and Moldovans prepare Cozonac, richly filled, usually with walnut paste, poppy seeds, Turkish delight, or cocoa swirls.

Saturday-Sunday midnight church service is very popular, even more so in the Balkans, especially Romania and Greece. Participants light candles from the holy fire passed around from the priest's flame. Fireworks or church bells often go off joyously at this moment. The participants would walk around the church with lit candles, before the liturgy continues. People take their lit candle home, making a smoke cross over their front door for a blessing.

The congregation lighting their candles from the new flame in a Greek Orthodox church in Australia. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

On Sunday morning, families walk to churches together, carrying special baskets with embroidered towels at the bottom. They contain coloured eggs, local sweet bread, meat, salt, butter, and cheese. People form rows among themselves outside the church. Then, a priest goes around sprinkling holy water on those standing. The water is believed to wash off the sins of people and bless the food. This tradition has even found its way into Poland, a predominantly Catholic country.

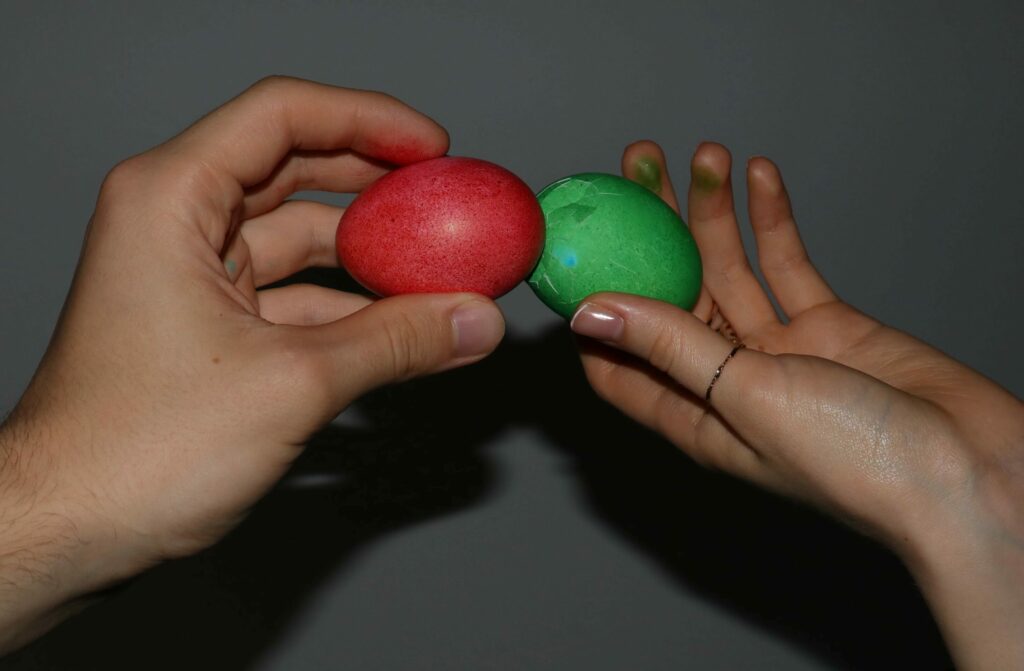

Another fun tradition is egg cracking. Two people would take eggs and tap them against each other, trying to smash the opponent's one. In many families it is believed that an uncracked "winning" egg brings good luck.

Egg tapping tradition. Credit: Kosmos Khoroshavin

A crucial part of every Easter celebration is the Paschal feast, shared at home with your family. This is the time to bring out meats, cheese, eggs, the sweet bread and various other dishes. This marks the culmination of the Great Lent and the start of the Paschal season.

While making a bigger accent on Christianity, Orthodox Easter has a uniting effect on people. A lot of secular Christians, agnostics and atheists celebrate Pascha. It’s the perfect occasion to gather with family, enjoy a festive meal, and take part in traditions that bring generations closer — whether for faith, culture, or simply the joy of being together.