Belgium's system of creating "social bubbles" to restrict contacts and prevent the spread of the coronavirus among the population is effective, a study published in the scientific journal Nature Communications shows.

The study shows that Belgium's "household bubbles" have the potential to reduce hospital admissions by about 90%, and was carried out by 12 researchers from the universities of Brussels, Antwerp, Hasselt and Leuven.

Microbiologist and former Sciensano spokesperson Emmanuel André, who shared the study on Twitter, stated that "the effectiveness of the 'Belgian Bubble' was now recognised in the scientific literature."

L’efficacité de la « Bulle Belge » désormais sacrée dans la littérature scientifique. @HensNiel https://t.co/8xDMdYnv1v

— Emmanuel André (@Emmanuel_microb) March 10, 2021

A household bubble, as defined by the researchers, is a "unique combination of two households, who meet during the weekends, in which the oldest members can only differ three years in age," to reduce intergenerational mixing.

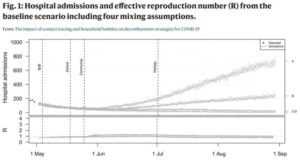

As Belgium's gradual deconfinement requires "detailed models to simulate the virus spread," the study started from a baseline scenario in which businesses, schools and community activities are gradually reopened.

Credit: Nature Communications

The default scenario with household bubbles shows an average reduction in the average number of hospital admissions of 53% in June, and 75% in August compared to the baseline scenario.

In the figure, the evolution of the A and B curves (indicated on the right) include an increase in social contacts within a community, which has a clear impact on projected hospital admissions. On the C and D curves, the number of social contacts remains stable.

Related News

- Relaxing outdoor measures not same as larger social bubble, virologists warn

- Cheat Sheet: Belgium's timeline for relaxing coronavirus measures

- Infection risk is 10 to 20 times lower when meeting outside

Additionally, A and C include an increase in B2B (inter-company) mixing. In the B and D curves, the inter-company mixing remains constant, showing that without the increase in community social contacts, the effect of inter-company mixing seems minimal.

With no extra social contacts outside this household bubble - meaning if the bubbles are fully respected sever days a week - the average number of hospital admissions can be reduced by 93% by August.

If the bubbles are respected less strictly - fully respected only two days a week - the effect is less pronounced but the average number of hospital admissions in August can still be 41% lower than in the baseline scenario.

However, if both inter-company and community social contacts increase, the "household bubble" and contact tracing scenarios are not sufficient, and the number of hospitalisations continues to increase over time.

Maïthé Chini

The Brussels Times