Is the EU prepared to mitigate and adapt to the impacts of a warming Arctic on the environment and the economy? How should EU strike the right balance between protecting the environment in the Arctic region and supporting the people living there, in competition with non-EU Arctic countries?

These were the main questions at a webinar on Wednesday (5 May) organised by The Brussels Times together with the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) and with participation of a high-level panel of experts and decision-makers.

The Arctic region, spreading around the North Pole, and above a line of latitude of 66.5 degrees north of the equator, includes not only the northern parts of two EU member states, Sweden and Finland, but also Greenland and the Faroe Islands, which are autonomous parts of Denmark. The three EU member states are members of the Arctic Council, besides Iceland, Norway, Canada, the US and Russia.

As the EU-funded Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) has shown in its recent European State of the Climate report, the Arctic is one of the regions most impacted by climate change. C3S is implemented by ECMWF, which has a four-decade history of numerical weather prediction.

It is already no secret that the Arctic is warming twice as fast as the rest of the globe and experienced record temperatures in 2020. In September 2020, Arctic sea ice reached its second-lowest minimum extent since 1979, behind the record minimum of 2012, with a monthly mean extent 35% below the 1981–2010 average.

Globally, 2020 was one of three warmest years on record. Over northern Siberia, temperatures reached more than 6°C above average for the year as a whole, with dry conditions and record-breaking fire activity during summer. In the adjacent Arctic seas, sea ice was at a record low for most of the summer and autumn.

In 2020, the annual temperature for Europe was the highest on record. Winter was particularly warm, also setting a record, at more than 3.4°C above average.

The importance of data

“The best way to understand both present and future climate risk is reliable, accurate climate data,” said Samantha Burgess, deputy director of C3S. “You cannot manage what you cannot measure and this is very true for the climate. Unless we understand how our climate is changing and what risks that change may bring, we cannot plan for a climate-resilient future.”

She explained that C3S is collecting data from dozens of satellites circling the earth as well as from sensors on-site reporting from the oceans, land, and air around the world. The measurements make up a whole ecosystem of scientific data and are open to everyone. For those who want to learn and form their own opinions, such data is indispensable.

This includes the EU, which is updating its current Arctic policy to align with the European Green Deal, the ambitions of which are also supported by the Copernicus programme.

Alain Hubert, a Belgian explorer and founder of the International Polar Foundation, has experience of both the Arctic in the north and Antarctica in the south of the planet. He was the first Belgian to have reached the North Pole in 1994 and directed the construction of “Princess Elisabeth Antarctica Research Station”, the world’s first zero-emission station, fuelled by wind turbines and solar panels.

Early on during his explorations in both regions, he realised that something was wrong with the climate. The ice was not as thick and strong as it used to be. He agrees that satellite images are important but observations on the ground are also needed. From the analysis of Antarctic ice cores, it was possible to see increasing concentrations of CO2.

He warns that the melting ice in the Arctic and Antarctica will have disastrous consequences for the Earth but in different ways. The Arctic is mainly covered by an ocean which means that, when the sea ice is melting, it has no direct effect on the sea level rise. But the ice is acting as a white shield, reflecting the heat from the sun in Summer. With less ice, more heat is absorbed resulting in climate change.

On the opposite, Antarctica is a continent. When the glaciers and ice shelves are melting and released into the ocean, it has a direct and worldwide effect on the rising of the sea level. While Antarctica is still covered by ice and will remain so for the foreseeable future, some ice is being lost in West Antarctica due to warming ocean currents eating away at the ice from below.

At the webinar, he warned against the threat of an “open” Arctic without ice where industrial actors would be roaming around extracting the mineral resources of the region. “Europe isn’t very far from the Arctic and would be heavily affected. EU plays an important role but is not the biggest player and should be on its guard against other countries that are guided by economic and geostrategic interests.”

The experts from the European institutions largely agreed with him and stressed what the EU is doing or planning to do to preserve the Arctic.

The need for EU Arctic policy

“The Arctic region means a lot to the EU, and not only because that three member states are close to the region, besides two other European countries, Norway and Iceland,” said Michael Mann, EU Special Envoy for Arctic Matters at the European External Action Service (EEAS).

EU is involved in legislation concerning the Arctic and currently working on updating its Arctic policy and increasing its research budget (Horizon Europe). What this will mean for economic activities in the Arctic region is not clear since the EU, as other players in the region, also has an interest in the natural resources in the region.

“The Arctic is a living region,” Mann said. “We need to strike a balance between preservation and supporting people living there, inclusive indigenous people. We can help them to develop green technologies.”

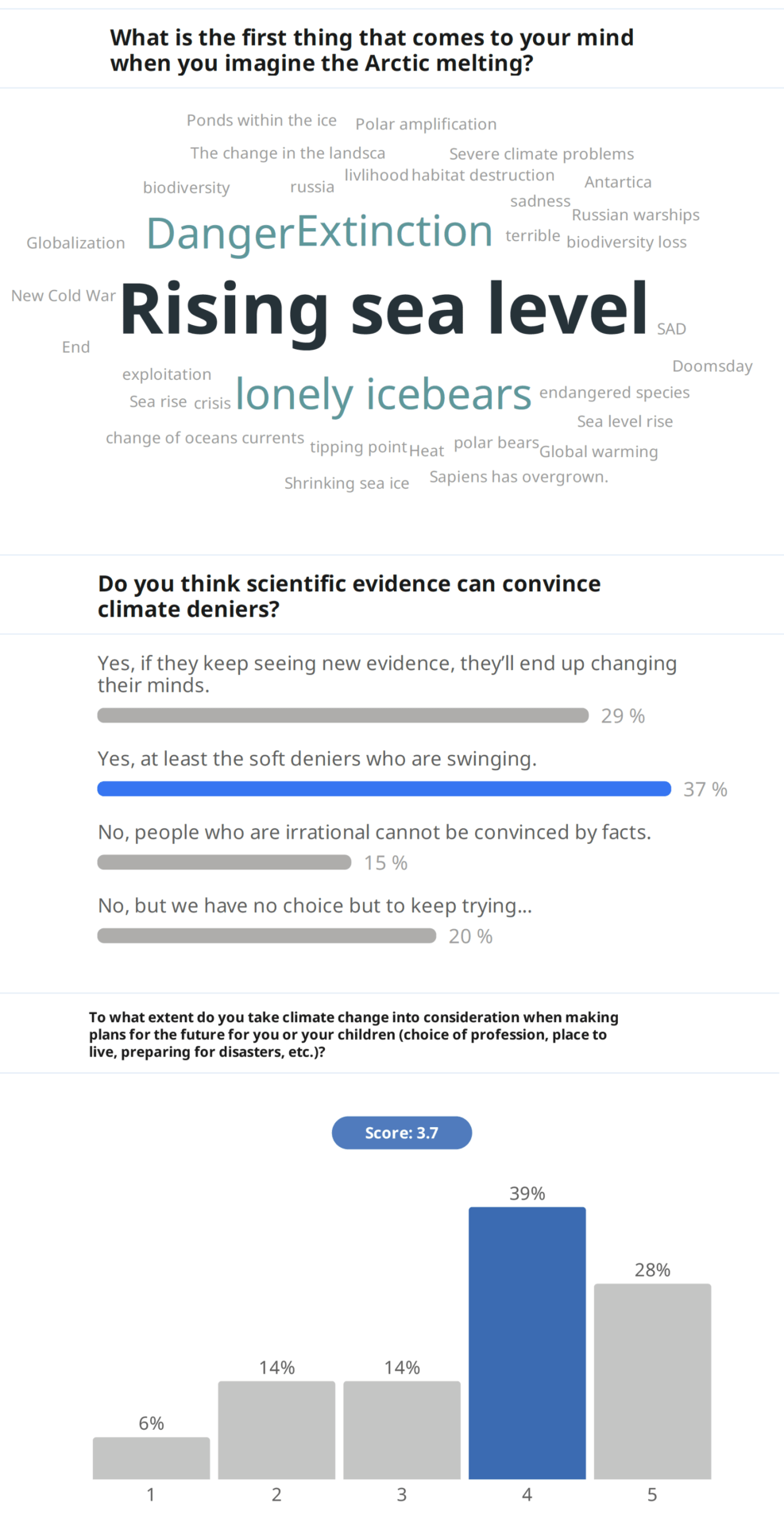

Results from live polls that were answered by participants during the webinar.

The Arctic is also a space where European, transatlantic, and Russian interests intersect but Mann was optimistic about reconciling the different interests, now when the new American administration has returned to the Paris Agreement and pledged to cut greenhouse gas emissions. Even Russia, worried about the thawing of the permafrost in Siberia, has woken up, according to Mann.

Russia, with an Arctic population of 2.5 million, is set to take over the chairmanship of the Arctic Council in May.

The cost of inaction

Finnish MEP Miapetra Kumpula-Natri is co-chair of the parliamentary Intergroup “Climate Change, Biodiversity and Sustainable Development”. In Finland, half a million people are living in the north of the country, above the Arctic circle. “They would be the first to suffer from climate change. We must enable them to continue to live in the region.”

“Our response to the challenges in the Arctic region is the European Green Deal,” she said, adding the need for an updated Arctic strategy. There is no quick win and most of the investments required will have to come from private sources. “We should start regulating across different relevant working groups, using all data available. We cannot deal with climate change working in silos.”

Scientists are warning about the “tipping points” in climate change, such as the melting of the ice in the Arctic and Antarctica, the thawing of the permafrost and the deforestation and burning of the rain forest in the Amazon, when it will be too late to save the planet. We are not there yet but approaching the abyss if not global warming will be limited to 1,5 – 2 °C by cutting GHG emissions.

“We need to adapt to what is unavoidable and avoid what we cannot adapt to,” said Elena Višnar Malinovská, head of the unit for Adaptation to Climate Change in the Directorate-General for Climate Action at the European Commission. Already tens of thousands of Europeans are victims of coastal flooding and extreme weather fluctuations.

“We need both mitigation and adaptation measures,” she underlined and added that the annual economic price of inaction in the EU can be measured in billions of euros. Action should be based on sound data, using past and current data to project the changes while taking into account that the changes and damages in the future are not linear because of the risk of tipping points.

A note of hope was expressed by Rowan Douglas, Head of Climate and Resilience Hub at Willis Towers Watson, a global risk management company. In the near future, companies will have to take climate change into account in their business decisions and declare the risks in their financial statements, he said and referred to the coming climate change conference in Glasgow in November 2021.

“Climate change risks are foreseeable and will have to be taken into account, legally and financially,” he said. “Climate change is a credit risk and will affect the prices of assets and the allocation of jobs.” EU is an epicentre in this development. Already next year, all companies will have to disclose the impacts of climate change, including systemic risk scenarios.

While in the past people mainly related to nature through religion or poetry, today we also need to connect to nature by scientific data collection and financial reporting to save the planet. The older generation might have failed but, as one of the panellists, whose son is studying climate science, said, “I have faith in the younger generation. They know the truth.”

The Brussels Times