Scientists in London and Texas have discovered the mechanism behind one of the last antibiotics able to combat the most drug-resistant bacteria. The discovery could lead to the development of even more effective antibiotics.

Colistin is an antibiotic nowadays usually reserved for the treatment of infections where nothing else will work, but despite being over 70 years old, the process the drug uses to kill bacteria has remained a mystery.

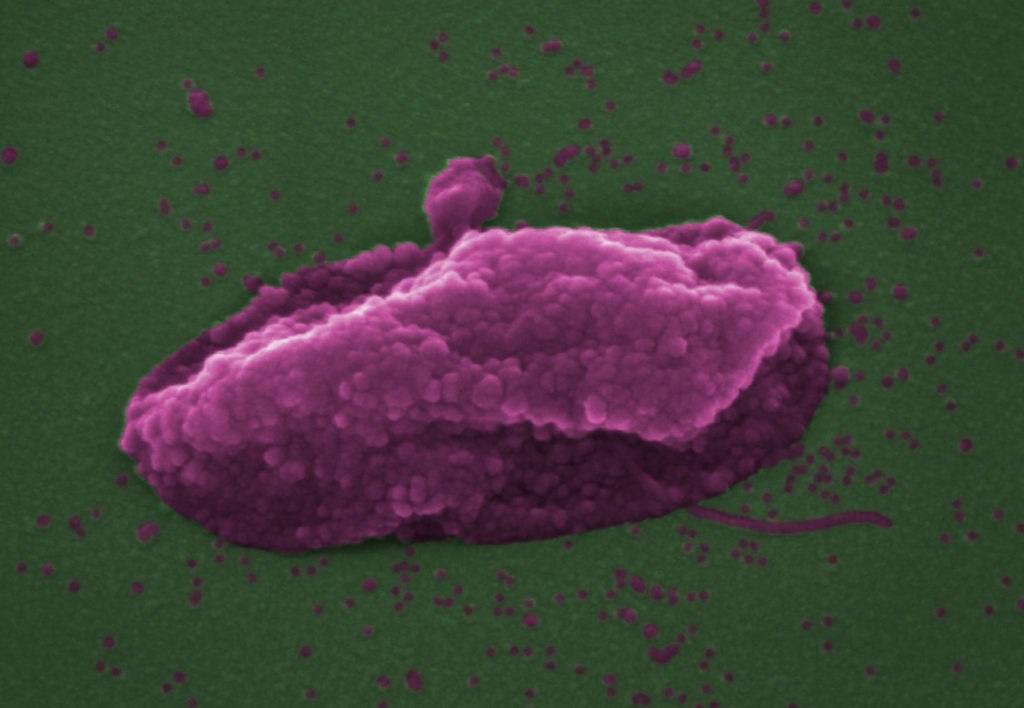

The answer, according to a paper published by scientists from Imperial College London (ICL) and the University of Texas, is extremely simple: the drug targets a chemical inside the bacterium, and once locked on, punches a hole in the bacterium’s membrane, popping it like a balloon and killing it.

Until now it was known that colistin targets a lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in the outer membrane, but no one could figure out how it dealt with the inner membrane, where far less LPS is present.

“It sounds obvious that colistin would damage both membranes in the same way, but it was always assumed colistin damaged the two membranes in different ways,” said Dr Anthony Edwards from the department of infectious disease at ICL in a press release.

“There’s so little LPS in the inner membrane that it just didn’t seem possible, and we were very sceptical at first. However, by changing the amount of LPS in the inner membrane in the laboratory, and also by chemically modifying it, we were able to show that colistin really does puncture both bacterial skins in the same way - and that this kills the superbug.”

Related News

- Belgian researchers pave way for more effective treatment of breast cancer

- Research: Eating insects is also good for farm animals

- Research: Ibuprofen use is not a risk factor in Covid-19 outcomes

But the importance of the new research goes further than simply solving a long-standing mystery among bacteriologists. It could lead to a new generation of drugs to combat hard-to-treat infections.

The researchers looked at Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which causes serious lung infections among people with cystic fibrosis. And they found that an experimental drug called murepavadin made the bacteria involved grow more LPS in their inner membrane, causing them to become more vulnerable to colistin.

The approach is for the time being experimental, but clinical trials are expected to begin soon, and by combining murepavadin with colistin, could lead to a whole new way of tackling intractable infections.

“As the global crisis of antibiotic resistance continues to accelerate, colistin is becoming more and more important as the very last option to save the lives of patients infected with superbugs,” said Dr Akshay Sabnis of ICL, lead author of the study.

“By revealing how this old antibiotic works, we could come up with new ways to make it kill bacteria even more effectively, boosting our arsenal of weapons against the world’s superbugs.”

The research paper is published in the latest edition of the journal eLife.