LVC drivers in Brussels, such as those who work with digital platforms like Uber and Heetch, are protesting on Thursday morning to demand reform of their sector.

The conflict began when Brussels city authorities invoked a 1995 law concerning “radio communication devices”, banning drivers from using their cell phones to take fares, which effectively left Uber unable to operate in the Belgian capital.

“This law needs to change because we’re not in 1995 anymore,” Mujahid Zaman, who drives with Uber, told The Brussels Times.

“This is Brussels - this is the capital of Europe. I don’t know what’s happening here.”

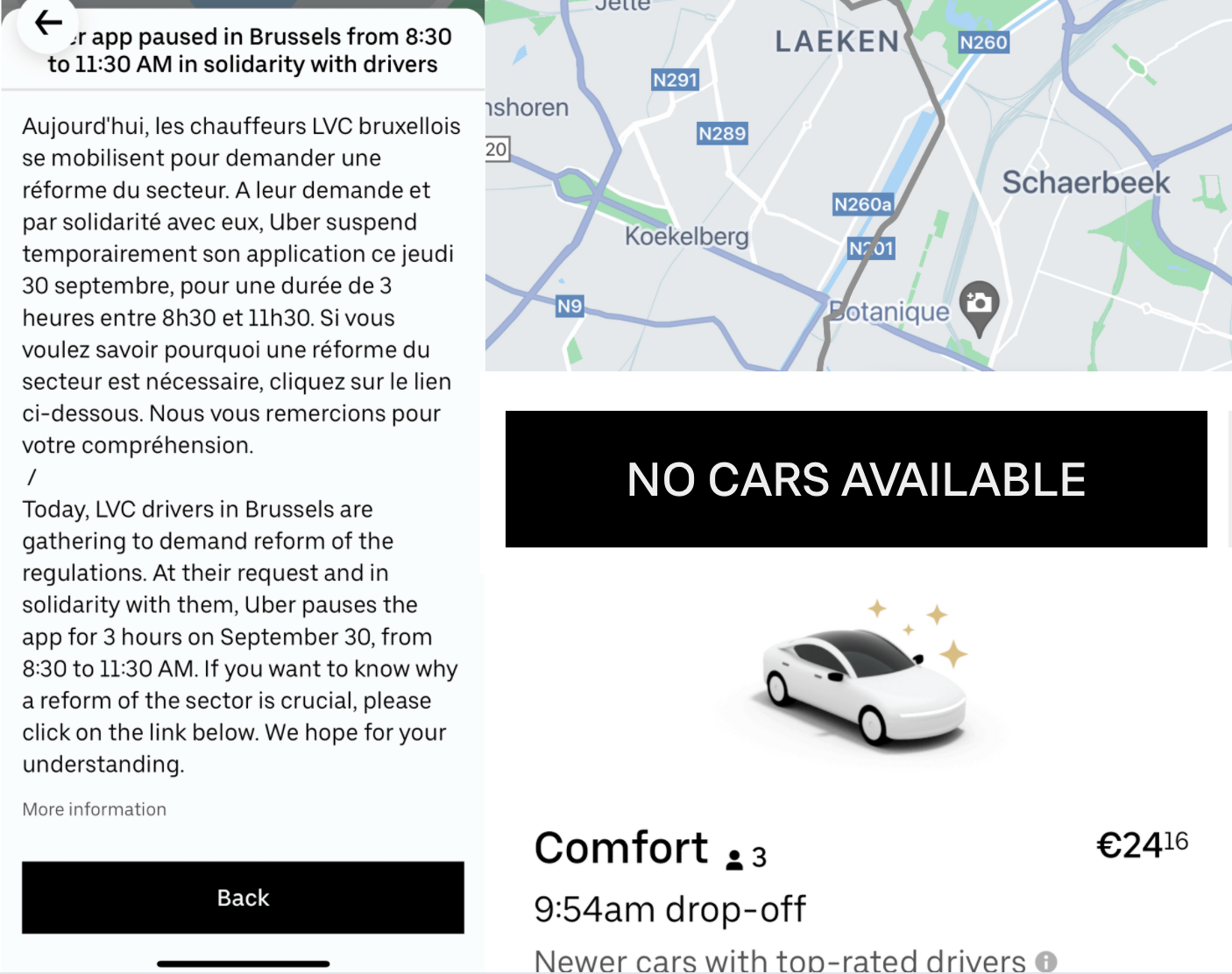

Zaman is joining other Uber drivers in this morning’s protest, and Uber has temporarily disabled its app in a show of solidarity with them. Users attempting to book a ride between 8:30 AM and 11:30 AM saw an error message explaining that drivers are demanding reform.

For Zaman, it is not only his livelihood that is at stake. Born and raised in Brussels, Zaman used Uber to launch his own transportation business a few years ago, creating a company that consists of multiple luxury vehicles and hired drivers.

The cars in his fleet constitute a significant investment and ever since the cell phone ban came into effect he has faced the possibility of those cars being seized by Brussels Mobility.

“When I invested €47,000 in a BMW 5 Series, nobody in Brussels Mobility said I couldn’t drive Uber here. Then back in February or March, I got a letter saying that I can’t drive anymore and that my investment is finished.”

An atmosphere of uncertainty

“The taxi and LVC sector in Brussels has been waiting for a reform for seven years," Uber said in a statement expressing support for Thursday's protest. “Without a reform now, as a rider, you may not have the same mobility opportunities as today anymore.”

They say that the temporary disabling of their app is a measure that's “exceptional and unprecedented in Europe. It is in line with the seriousness and urgency of the situation in Brussels. We stand by drivers who want to secure the future of your mobility in Brussels.”

Brussels Minister-President Rudi Vervoort promised taxi reform before the end of summer but failed to deliver.

It was only on Wednesday – the eve of these most recent driver protests – that a draft plan was revealed.

In the meantime, Uber drivers have worked for months in uncertainty, with stories circulating about high fines and seized vehicles, wondering whether they might be next.

“Every day we are having controls by Brussels Mobility where they tell us that we can't drive anymore, that we will get a fine and that after the fine our car will be taken and we won't be able to drive in Brussels anymore,” Zaman said.

“Every day, a driver has an issue. They’re threatening us. It’s been going on for months and needs to be sorted out as soon as possible.”

from Uber.

Zaman is frustrated. He’s a self-employed contractor, the owner of a registered company with a VAT number, and pays his taxes.

“We're working, I'm paying taxes. I don't know what else they want us to do. I really don't know.”

He’s been trying to register an additional vehicle - a €67,000 Mercedes - since December of 2020 so that it can be driven as part of his transport company’s fleet.

“The process is normally supposed to take three months,” said Zaman, who has yet to hear back regarding that registration.

“Vervoort doesn’t reply to my emails or my letters.”

A new business model

For Vervoort and other proponents of the mobile phone ban that threatens the livelihoods of Uber drivers like Zaman, it’s never been about the 1995 law itself. They are fundamentally opposed to Uber's business model, in which drivers aren’t employees but self-employed contractors without access to social rights, standard wages or any of the other protections that come with traditional employment.

There are also concerns about what companies like Uber and Heetch mean for the traditional taxi sector and those who work in it, as the new companies’ dynamic pricing and digital convenience lures customers away from the “stand-on-the-corner-and-wave, pay-by-the-meter” method now seen as old-fashioned.

But Zaman isn’t overly concerned with the political battle.

“We are not working for Uber,” he emphasises. “I’m working as an independent contractor. I have my own company.”

He also has a family, two children and a wife, who are relying on that business to support them financially.

“It’s difficult,” he said, en route to the driver protest. “This morning my kids were saying to me, ‘Go, papa, and show them with the strike that we’re not going to lose this battle.’”