The lockdowns have tested the city and forced it to confront key questions about its future. Derek Blyth looks back at an extraordinary moment in our time and identifies six ways that Covid could change the EU capital forever.

There is no need to go over the events of the past 18 months. You were there. We all went through roughly the same experience. One day, we were trapped in the first Belgian lockdown, enviously watching people drinking on café terraces in Stockholm. Days later, we were thankful not to live in Paris where residents had to carry around a printed document any time they went out for a tin of cat food.

As always, Belgium turned out to be the most average country in Europe. Not as strict as France, not as relaxed as the Netherlands. Somewhere in the middle. But then towards the summer of 2021, something unexpected happened. Belgium was suddenly the country with the second-highest vaccination rate in the EU, after Malta. Who would have thought?

For most democracies with freedom of movement carved into their constitutions, the lockdown came as a shock. Something they had never seen before. But not Belgium. This little country has been invaded so many times in the past that lockdown is almost the normal state. People here know better than anyone that the good times don’t last forever. Enjoy your steak-frites, because it might be your last meal.

Nor were deserted streets such an unusual sight. We had been through that trauma just a few years earlier following the 2015-16 terror attacks. And yet the early days of lockdown did feel like a new kind of terror. Our thoughts became gloomily apocalyptic as the virus tightened its grip.

Then an unexpected moment of Belgian surrealism briefly lifted people’s spirits. The far-right Hungarian MEP József Szájer, whose party Fidesz opposes LGBT rights, was trapped breaking lockdown rules by attending a gay sex party. When police raided the downtown apartment, Szájer attempted to evade arrest by scrambling down a drainpipe. Only a Belgian cartoonist could have imagined such a scenario.

Of course, we shouldn’t mock human frailty. But with the endless statistics grinding us down, what else could we do? An unofficial sign went up outside the building next to Ancienne Belgique where Szájer met his downfall. “The political career of József Szájer ended here when he tried to flee the authorities using this gutter,” it read. Unfortunately, this solemn plaque has disappeared, or it might have become a tourist attraction, like the spot in Rue des Brasseurs where Paul Verlaine shot his lover Arthur Rimbaud.

But that was the only fun to be had in a grim year. Whenever we ventured out of doors, masked and distanced, it was to walk through a ghost town, where life had come to a sudden end in March 2020.

When the city began to reopen this summer, it seemed a good moment to take stock of the damage. I set off on a long walk, expecting to find a ruined city, like Ypres 1918 or Berlin 1945. It was sad to come across the casualties, like Demeuldre on Chaussée de Wavre, where rich Ixelles families used to buy their dinner sets, and the famous but faded Taverne du Passage in the Galeries Saint-Hubert, where Angela Merkel enjoyed some typical Belgian cuisine.

There were other victims, too. The romantic bar-restaurant Cercle des Voyageurs in the city centre went bust at the end of 2020. Four months later, the convivial beer restaurant Restobières in the Rue des Renards pulled down the shutters. A few days later, the traditional Brussels café La Brouette on Grand’Place served its last beer.

It became clear that Brussels would never be the same again. But what kind of city will we see emerge from lockdown? Here are six changes that look like they are here to stay.

Cars are on the way out

One change is immediately obvious. People are moving around differently. Brussels is now teeming with bikes, along with e-scooters and ever more weird forms of transport. And people are also walking more.

It wasn’t just the pandemic that did it. The city was already trying to persuade people to kick the car habit with projects like the pedestrian zone on Boulevard Anspach and the traffic-free artery down Chaussée d’Ixelles. But the pandemic accelerated the mobility reboot, with bike lanes created along major routes and squares redesigned for pedestrians.

Another ambitious plan, to clear two monumental sloping ramps below the law courts of illegally parked cars, was finally achieved in the early summer. Despite protests, the sloping ramps have been turned into public spaces for pop-up events, including an urban beach, climbing wall and bike repair workshop.

Streets are for living

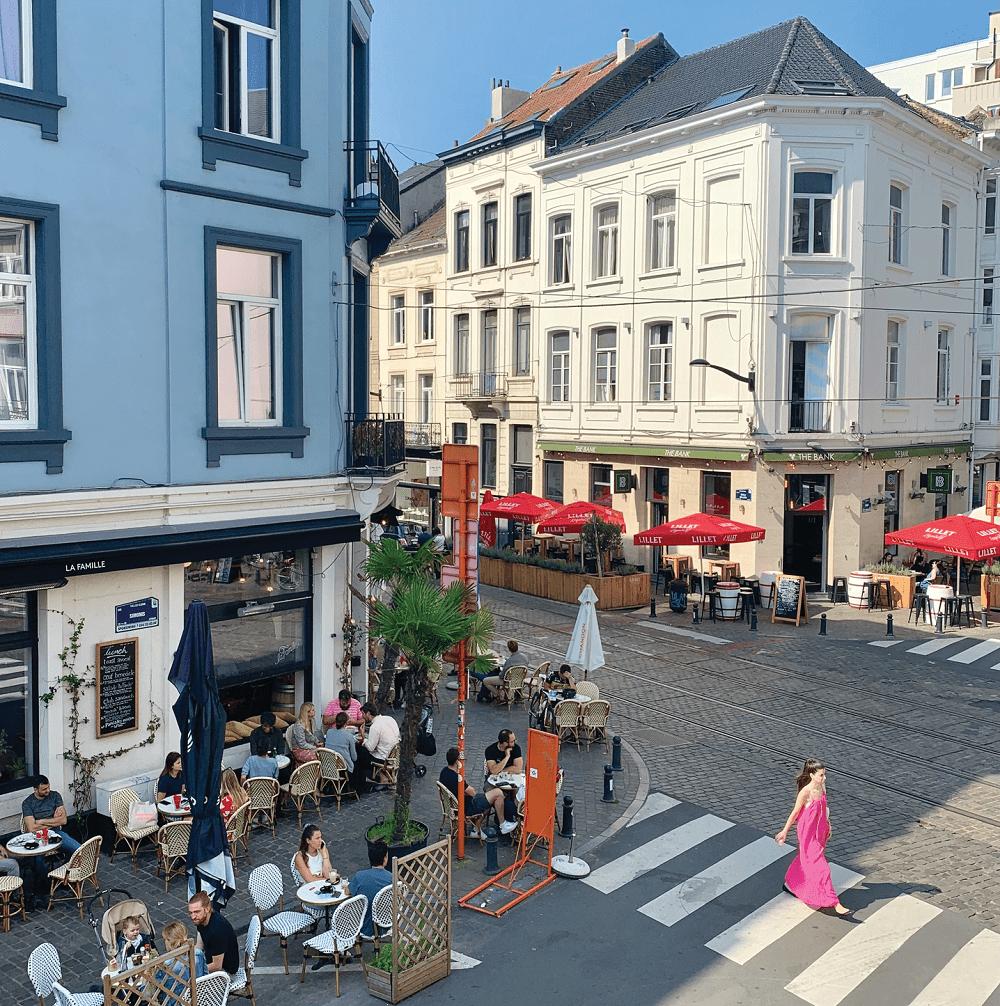

Another consequence of the pandemic that is likely to stay is the shift to outdoor living. We somehow became tougher, and more relaxed, during the period when indoor life was banned. People are now perfectly happy to sit on a street terrace created by suppressing two parking spaces and bringing in a carpenter to knock together a temporary screen out of industrial pallets.

Credit: Pascal Smet

As a result, the city has a cool Scandi look about it. The change is helped along by the city’s decision to cut the speed limit to 30km an hour across the entire region (except on major roads). Some drivers have protested, as you might expect in a city built around fast roads and easy parking. A petition to scrap the plan gained 50,000 signatures. But it looks like we are moving towards a new type of relaxed urban living that would appeal to someone moving here from Stockholm. Again, who would have thought?

Homes will turn into offices (and offices into homes)

The biggest change to urban life in Brussels is the shift to home working. Without the pandemic, it is unlikely many organisations would have allowed staff to work remotely from their Brussels apartments (or holiday house in Tuscany). But the experiment has largely been a success. The work got done. And a lot of people have decided they don’t want to go back to the office.

That could hit Brussels like an earthquake. Over the past 50 years, the EU capital has based its economy on providing large, boring office buildings for financial organisations, government ministries and EU institutions. But what if people decide they don’t want to go back to the office more than one or two days a week?

The EU neighbourhood could empty out as officials work from home

The change would have a catastrophic impact in the European Quarter. Originally a district of handsome 19th-century townhouses, the quarter was rebuilt from the 1960s as a nine-to-five office district. As recently as the summer of 2019, the EU Commission was showing off its plans to build two soaring skyscrapers on the Rue de la Loi.

The project was fiercely opposed by local action group Arau for ignoring “the principle of sustainable cities built for people.” Now EU staff have gained a taste for home working, the two towers might never get built. In May 2021, the EU Commission revealed that it would abandon half of its office buildings over the next ten years.

It could be that the EU Quarter will turn into a ghost town. It wouldn’t be the first time in Brussels. Back in the early 1970s, the city started work on an ambitious office district known as the Manhattan Quarter. The old neighbourhood around Gare du Nord was destroyed to put up a cluster of gleaming skyscrapers. But then the oil crisis crashed the economy, and the plan was scrapped, leaving just a few isolated office buildings surrounded by wasteland.

The city currently has more than one million square metres of empty office space, according to research organisation JLL. The modern green office buildings are unlikely to remain empty, but the older office buildings may never get filled. One plan under consideration is to turn the empty offices into apartments. But it is hard to see how they will persuade people that an apartment on the Rue de la Loi overlooking four lanes of commuter traffic is where they want to live.

Meetings will be virtual

Another big change that will hit Brussels hard is the shift to online meetings. During the pandemic, everyone got the hang of Zoom or Microsoft Teams. It turned out to work just as well as arranging for 50 people to fly to Brussels for a meeting. And it was a lot cheaper. What if the EU and other big organisations decide that virtual meetings are the future?

This would have a deadly impact on the hotel and restaurant sector, which depends heavily on people with generous expense accounts rather than tourist euros. Already, several hotels have closed down, including the landmark Metropole which has stood on Place de Brouckère for 125 years and welcomed many of the most famous names in 20th-century history. The hotel had already been struggling to fill its rooms, citing the terror attacks and the pedestrian zone as causes. But maybe, like many hotels and restaurants in the city centre, it had become a little faded and unfashionable.

No one knows if business travel will make a comeback, but it seems likely those big Brussels hotels will struggle to fill their expensive rooms.

Tourists will want something different

Despite the gloomy outlook, the hotel sector is still surprisingly upbeat. Some 30 new hotels are due to open in Brussels, adding 3,000 guest rooms to the current 37,000. The most exciting – but also the most discreet – opened its doors recently on Place des Martyrs. This neat Neoclassical square in the heart of the city named after a monument to the heroes of the Belgian revolution used to be a sad, deserted spot. But the new Hotel Juliana is a sign of a neighbourhood on the rise.

Hidden behind a Neoclassical façade, the 43-room hotel has been reshaped by Italian designer Eugenio Manzoni to create a sublime urban retreat. The elegant guest rooms come with unique touches, including painted wallpaper, frescoes and paintings from the owner’s private collection.

But will there be tourists to fill those rooms in a city that already struggles to attract visitors at weekends and during the summer months? With a budget of €7.6 million, Visit Brussels has worked with 200 local organisations to come up with a post-covid recovery plan. In early July, it opened two bike hubs at the Grand Hospice in central Brussels and See U in Ixelles. Aimed at tourists and residents, the temporary hubs offer bike rental, city tours and practical information.

With a good plan in place, Brussels could emerge from the pandemic as an alternative tourist destination where people go to explore the city by bike, eat in unusual places and meet local people.

Brussels will go green

Locked down for several months in small city apartments, many people began to see the advantages of the suburbs. Without the pressure to commute, you could sit out the lockdown in a house with a garden somewhere on the edge of Brussels. Or you could go for a rural location in the Ardennes with a view of cows from your desk.

The city will have to move fast if it is to stop a repeat of the urban exodus of the 1970s, when thousands of families moved out of Brussels to the peaceful suburbs. That means cutting pollution, creating more green space and somehow persuading people that Brussels is a good place to live.

One vision of the future is already taking shape along the canal at the Tour et Taxis neighbourhood. This massive project has transformed an old industrial site dominated by 19th-century warehouses, marshalling yards and Europe’s largest goods station. The site now offers an astonishing alternative vision of Brussels with sustainable architecture, eclectic start-up companies and wild meadows (see cover story).

Despite all the changes, Brussels has not lost its weird sense of humour. When a competition was announced to name 28 streets in the new Tour et Taxis quarter, locals were quick to respond with quirky suggestions. It means you can walk down a street next to the Gare Maritime named Ceci n’est pas une rue – a reference to Magritte’s famous painting Ceci n’est pas une pipe. Corona may have changed our lives. But Brussels surrealism has survived the pandemic.

By Derek Blyth