King Leopold II took control of Congo during the 19th century scramble for Africa, but his ruthless plundering of the country is a stain on Belgium’s reputation. As Belgium finally confronts his legacy, we look at the history and the ongoing controversies linked to the country’s colonial era.

It’s one of those things you do with visitors to Brussels. You take tram 44 from Square Montgomery to Tervuren, or you drive out along the sweeping avenue that begins at the Cinquantenaire Park, visit the Africa Museum, and then stroll through a park that looks like Versailles.

You might not realise it, but the invisible hand of King Leopold II has shaped your entire day. He created the park, the avenue, the tram line and the museum. It was all part of an ambitious marketing plan to showcase his colony in the Congo. He wanted to impress visitors to the colonial exhibition he organised in Tervuren in the summer of 1897. He aimed to show the world that he was bringing civilisation to Africa.

But there was a dark side to Leopold’s plans. Walk into Tervuren’s main square and climb up the slope to the parish church. There are seven gravestones lined up against the wall of the church. Inscribed on the graves are names, almost worn away. Ekia, Gemba, Kitukwa, Mpeia, Zao, Samba and Mibange, the names read. Nothing else. For decades, this was a story the country preferred to forget.

Currently, the Africa Museum is organising an exhibition that aims to shed light on the seven people buried in these graves. Held to mark the 125th anniversary next year of Leopold’s colonial exhibition, it will take a hard look at the tragic ‘human zoo’ that was a key pillar of Leopold’s plan.

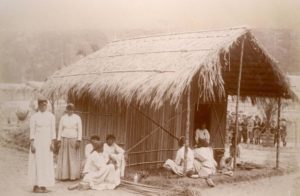

Down by the lake, where locals picnic and walk their dogs, Leopold built three fake Congolese villages to house 267 men and women shipped from the Congo to entertain the crowds. The humans were put on display, paddling canoes on the lake or cooking over fires, while visitors looked down from a rope bridge.

The Congolese village at the Brussels International and Colonial Exhibition in Tervuren in 1897. Credit RMCA collection

But it was a wet Belgian summer and seven people died of flu, pneumonia, or some European disease. They were buried without any ceremony and their stories barely remembered until a few years ago. But they are now part of a national debate that is finally, after more than a century of silence, examining Belgium’s involvement in its African colony.

Grandiose dreams for the little kingdom

When he came to the throne in 1865, King Leopold II had ambitious plans for his little kingdom and its modest capital. He wanted to make Belgium a world power, and Brussels more beautiful than Paris.

But he needed money. And he realised, long before he became King, that the country was too small. On a visit to Athens in 1860, he commissioned a stonemason to carve a message on a marble slab removed from the Acropolis. ‘Il faut à la Belgique une colonie’ – Belgium needs a colony, it said. The marble fragment, sent to the Belgian finance minister, marked the beginning of a project that would reshape a large region of Africa.

Leopold got his colony eventually, after sending the Welsh explorer Henry Morton Stanley to map out the Congo river basin. This vast region – nearly 80 times the size of Belgium – was Leopold’s private kingdom for 20 years, providing him with an endless supply of natural resources including ivory, rubber and coffee.

By the late 19th century, Leopold was one of the richest people in Europe, ruling his colony from a timbered chalet next to the royal palace, but never setting foot on African soil. He spent some of his wealth on a string of pretty young women, but most of the money was devoted to ambitious architectural projects, including railway stations, hotels, law courts and museums. People called him the Builder King.

The country is dotted with Leopold’s grand projects, marked with the carved initials LL, including the Palais de Justice and the royal greenhouses in Brussels, Central Station in Antwerp, the military barracks in Laeken (now a European School) and the royal galleries in Ostend. He also owned the fabulous Villa Les Cèdres near Nice, once ranked the most expensive property in the world.

Leopold’s projects were often cloaked in secrecy. He constructed concealed entrances to his palaces and underground corridors for his mistresses. And in a similar spirit of concealment, his colony was named the Congo Free State, when it was neither free nor a state. He always claimed he was bringing civilisation to Africa, but his real aim was to extract Congo’s wealth.

His grand plans for Belgium sometimes flopped. The massive triumphal arch in the Cinquantenaire Park, planned for an exhibition to mark Belgium’s 50th anniversary, was not finished in time. It had to be replaced by a replica made of wood and plaster. Petit pays, petits gens – a petty country of petty people, Leopold complained. The arch was formally opened on the 75th anniversary, in 1905, although it kept the name Cinquantenaire.

Despite the neoclassical swagger, there is a sad emptiness in many of Leopold’s buildings. The royal palace in Brussels is an echoing shell that is deserted most of the time. The Palais de Justice is so vast that the country can only afford to fund the scaffolding that stops the building from falling down.

Leopold’s ghost

The country only began to seriously confront Leopold’s regime after the publication in 1998 of Adam Hochschild’s ‘King Leopold’s Ghost’, which detailed the systematic cruelty of Leopold’s rule. Hochschild shocked the world with the horrific figure of ten million Congolese dead in a ‘forgotten Holocaust’ – a figure some Belgian historians continue to dispute.

When the Africa Museum organised a major exhibition in 2005 to mark Belgium’s 175th anniversary, the museum’s director, Guido Gryseels, used the occasion to fire the opening shot in a radical plan to reinvent the museum. He had inherited a run-down bastion of unreformed colonialism, its glass cabinets filled with exotic trophies, stuffed crocodiles and explorer’s relics. Gryseels gently pushed the museum in a new direction. His exhibition Memory of Congo, The Colonial Era confronted the darker side of the Congo, brought in Congolese academics to fill the gap in the collective memory, and ended with a joyful celebration of Congolese independence.

The aim, he explained at the time, was not to condemn previous generations, but to stimulate debate on a neglected period in Belgian history. Since then, Gryseels has cautiously steered the museum towards a progressive approach that challenges the prejudices of white superiority and black inferiority that had shaped the institution for a century.

The country is still peppered with statues of Leopold, sometimes splashed with red paint to symbolise the bloodshed he caused. But they may not survive for much longer. The murder of George Floyd, an African-American killed by a police officer in the summer of 2020, changed everything. Across the world, protestors attacked statues seen as symbols of white oppression, from Robert E. Lee in Richmond, Virginia, to English slave trader Edward Colston in Bristol.

Defaced Leopold II bust, Tervuren

In Belgium, protesters attacked statues of Leopold II and other colonial monuments. Amid the ensuing turmoil, there was a change in tone from the Belgian establishment. Last summer, as the former colony, now the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), celebrated 60 years of independence, King Philippe issued a statement expressing his “deepest regret” for the “acts of violence and cruelty committed” under Belgian occupation. The parliament announced a truth and reconciliation commission to examine “without taboos” the country’s colonial history. As for the statues, the Brussels regional government set up a diverse working group of outside experts to figure out some answers: they are set to unveil their proposals in December.

Halle buries Leopold

In some places, though, authorities moved on their own. As protests reached the quiet town of Halle, south of Brussels, where activists attacked a monument to Leopold in the Albertpark. It had been placed at the park entrance in 1953 when the king’s reputation was still basically intact (at least in Belgium) for bringing prosperity and civilisation to the Congo.

Not any more. The statue of Leopold was covered in red paint. Someone scrawled the word ‘moordenaar’ (murderer) across the king’s face. The bust was pulled to the ground. But the council put it back and added a notice. ‘We won’t give in to vandals,’ it read. ‘We want to discuss.’ And so the statue of Leopold was back where it started, waiting for a verdict.

Standing opposite Leopold is another statue. ‘In Honour of the Colonial Pioneers,’ it reads. It was put up in 1932 by the Cercle Colonial in memory of three men from Halle who died in the Congo. Standing on top of the monument is General Jacques of Dixmuide, a hero of the First World War who gave his name to Avenue General Jacques in Brussels. An inscription praises his dedication to the Congo, while the figure of an African looks up in adoration. But Jacques, like Leopold, has lost some of his glory due to violent campaigns he waged in the Congo.

In early 2021, the action group Decolonise Halle came up with a plan for the colonial sculptures. “You can’t confront this sensitive episode in our history by simply removing the statues and putting them in a museum storeroom,” said Andries Devogel, a local teacher and campaigner. “You can use the statues to educate people – especially school students – about the colonial past of Belgium.”

A few weeks later, after consulting local residents and historians, the council finally announced its plan. It would keep the bust of Leopold, but take it down from its pedestal. And it would plant ivy that would eventually bury the figure of General Jacques. “It means we can remind people of the controversial role that our country played as a coloniser,” explained mayor Marc Snoeck. “But we also make it clear that our city strongly condemns the colonial horrors and that there is no place here for racism or discrimination.” The plan was supported by eighty percent of locals.

Halle is just one example. Other cities across Belgium have begun to grapple with the thorny question of Leopold II’s legacy. In the university town of Leuven, the council voted to remove a statue of Leopold from a niche in the Gothic town hall. In Ghent, the city hoisted a bust of him from its pedestal. And in Ostend, protestors stole a bust of Leopold and replaced it with a modern bust of the murdered Congolese leader Patrice Lumumba.

In other campaigns, protestors have tried to force councils to change the names of streets and avenues that honour Leopold II. Or they have urged the Belgian state to return Congolese art that was pillaged during Leopold’s reign. There is even a campaign to decolonise the Dutch language.

The coming exhibition on Human Zoos will add to Belgium’s understanding of its colonial period. The organisers will also look at similar human zoos in other European countries, as well as the United States and Japan. It is estimated that 800 million people visited these racist shows where as many as 30,000 people were exhibited. After 125 years of silence, the story of the seven graves in Tervuren is finally being told.