As a Belgian of Congolese origin, I bear the wounds of past generations who have suffered from colonial brutality. I still mourn the pain and the loss from the carnage of the colonial era. That is why I take offence at the statues of Leopold II that are still in place at crossroads, in squares and parks across Belgium.

When people raise a statue, they honour the actions of the person depicted. In the case of Leopold II, it means accepting and confirming his exploitation and subjugation of the Congolese people. The statues are effectively a white supremacist marketing strategy. They perpetuate racial humiliation and mask the true history of colonial rape.

A statue is not a history book. History books are supposed to reconstruct facts. Statues reconstruct memories, which may be laden with contradictory assumptions and interpretations.

Our collective memory is, by necessity, a contemporary exercise in which different groups explain their perceptions, express their emotions and display their ancestral scars on the public stage.

This can be done peacefully, through official commemorations. But as we saw in 2020, when communities feel ignored and ostracised, they show their rage in a more conflictual manner, by smashing statues.

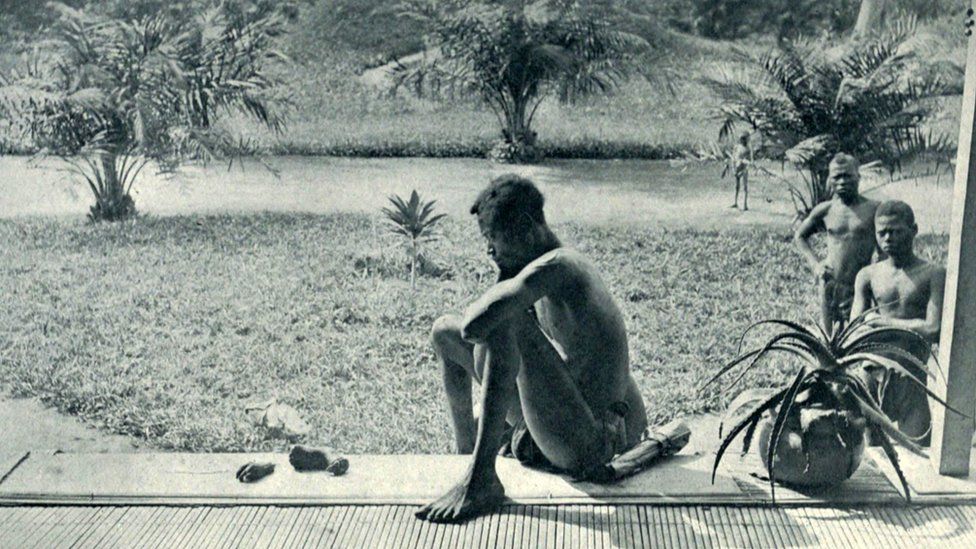

Black Lives Matter protesters in Brussels, June 2020. Credit: Igor Pliner

Vandalism, however, is also history. We should leave the damaged statues as they are because they bear witness to the way our Belgian and Congolese memories have changed as we start to question past actions and present inaction. The result today is a series of hybrid works and statues that reflect the troubled image of the current diverse population.

The bust in Ixelles of the bloodthirsty Belgian general Emile Storms, an early enforcer in Congo, is regularly doused in red paint. It is too bad that it has been restored to its original white stone: a vital sociological protest has been erased.

So, what should we do with Belgium’s colonial statues and monuments?

It is only natural that a community should ask itself questions if it no longer shares the values or actions of the person depicted in the statues. Once the person is debunked, it is time to move the statue. And the obvious place to move them is to a museum.

This is not about erasing history. The term ‘cancel culture’ is sometimes used to attack those of us who want to remove distasteful monuments. But that is not what we are doing. We need to keep the colonial statues as proof that the slaughter of the Congolese was once glorified. It is the glorification of these massacres that must cease.

At Bamko, we advocate a two-step plan. First, each monument should be given an explanatory plaque telling people what they really did. These plaques should stay in place for two to five years. This time could be used to arrange for their removal to various museums.

But a better solution would be to create an entirely new space dedicated to colonial statues, monuments and artefacts. This space would be a Decolonial Museum. It would focus on showing exactly how the Belgian state managed to dominate, rule, steal, corrupt and exploit people and communities across Africa. It would also show how they succeeded in painting a rosy image of themselves despite the atrocities they committed.

If we show how rich and powerful states like Belgium and people like Leopold II perpetuated their prestige, then we can rebuild our society on healthier foundations. That should take place alongside other measures to ensure our public spaces reflect our communities more accurately, with more racial and gender diversity in the figures celebrated. Only when we recognise the hurt and move to redress our collective memory can we start to repair the unspeakable damage from Belgium’s intrusion in Africa.