Belgian mustard producers are facing a difficult year, as their suppliers run into issues ranging from a disappointing harvest to impending war with Russia.

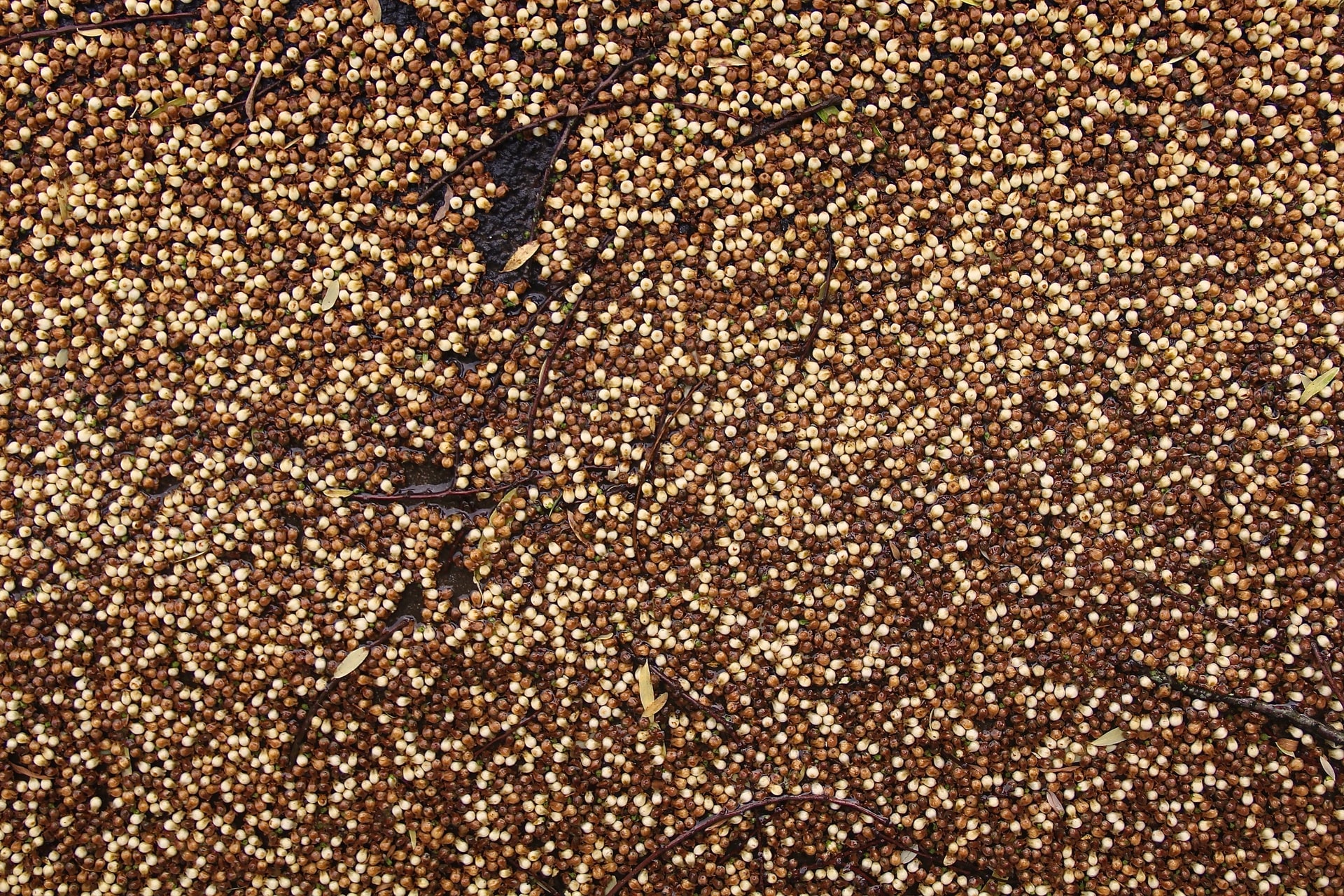

A worldwide scarcity of mustard seed is making matters difficult for producers like Ben Decock, who told Radio 2 that if this year’s harvest fails again, “we will really have a problem.”

Canada is the largest supplier on the global market, Decock says: “That country accounts for 80% of world production. [Last year] they had to deal with exceptional weather conditions, which reduced the yield of mustard seed by a fifth. Not only mustard, but also maple and rapeseed.”

This year, Canada is dealing with economic woes brought on by the Freedom Convoy that occupied the capital for weeks, shutting down major transport routes for trade.

But Belgium’s backup supplier – another major mustard seed exporter on the world market – is Ukraine.

War with Ukraine could threaten food security

“Ukraine is by far the leading agricultural producer in the hemisphere, and the strongest producer in Europe — with the potential to multiply its output several fold,” Bate Toms, a Western lawyer in Ukraine who is chair of the British Ukrainian Chamber of Commerce, told Politico EU.

Between Canada’s poor harvest and potential lingering transport issues, and the ongoing situation in Ukraine, there’s a worldwide scarcity of mustard seeds.

Related News

- Heineken announces higher beer prices

- Supermarkets need to be more transparent on food prices, says MP

- Worldwide shortage of fries due to logistical problems

- Task force to monitor impact of Ukraine war on Belgian agriculture

“Brown mustard seed in particular is almost impossible to get,” says Decock. “I can pay my supplier whatever I want, he just can't deliver it to me. In the past, there have also been bad harvests, but this is unprecedented.”

Mustard seed isn’t the only ingredient in the firing line: vinegar and salt, both used to make the mustard that’s ultimately spread onto a Belgian Martino sandwich, have also become more expensive.

“Vinegar even costs twice as much due to the coronavirus crisis, because of the greater demand for disinfectants,” Decock explained.

More expensive jars

As if all of that wasn’t enough, the glass jars used to package the mustard have also gone up in price.

“Transparent jars have become scarce because a number of glass smelters have closed down,” said Decock. “Metal lids have become 40% more expensive. I can hardly even find cardboard boxes to pack my jars in.”

The result of all the combined factors is a 30% higher production cost for a jar of mustard. Decock says that consumers won’t necessarily see that reflected in the price they pay in the grocery store, but that for producers the difference is huge.

undefined

Radio 2 reported that some stores are already hosting a smaller inventory of mustard, with some brands temporarily unavailable and others considerably more expensive.

In terms of 2022 being a year without mustard, Decock hesitated to make a prediction so soon. “This summer we will get an idea of the expected September harvest. If it is disappointing again, prices may rise further, shortages may increase and I can see some shops even running out of mustard for a while.”