The Underwear Museum fits in snugly with Belgium’s quirky and quirky art and culture scene, but it vanished shortly after it opened in 2009. The Brussels Times went searching for the world’s most celebrated collection of briefs, knickers and other nether garments.

Would you pay €5 to see your local politician’s underwear? What about €20 for Barack Obama’s?

Belgian anarchist artist Jan Bucquoy has made a living from displaying pants, knickers and even a knitted jockstrap worn by celebrities. He has turned his collection into the Underwear Museum, or Musée du Slip, which includes undergarments worn by the likes of Miss Belgium 1995, Belgian prankster Noël Godin (who famously pelted Microsoft boss Bill Gates with pies), two of the artists behind the Charlie Hebdo cartoons and Belgian politician Fadila Laanan.

Each exhibit is washed before display and presented alongside a certificate, which supposedly proves its authenticity. Some are framed in ornate antique settings while others are displayed as modern art: on a forlorn wire hanger with a tin of pilarchs speared on its end or demurely covering up the bottom half of a globe.

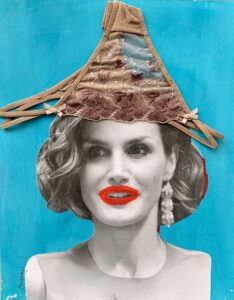

Pop art portraits of celebrities who were either unable or unwilling to provide their underwear hang alongside, with pairs of pants wrapped around their heads nonetheless. A lipsticked former French President Nicolas Sarkozy proudly gazes out from under his tri-colored Y-fronts – a modern day Napoleon – while pop art pioneer Andy Warhol sports a sequined thong like a witch’s hat.

The aim of this tongue-in-cheek collection? To break down the hierarchies that divide people, according to Bucquoy, its founder. “If you are scared of someone, just imagine them in their underpants. The hierarchy will fall and you will see that this is a guy like any other. We are all equal, all brothers,” he said on its opening in 2009. “If I had portrayed Hitler in his underpants there would not have been a war. I think in this way you can contribute to a better world.”

The vanishing museum

The museum quickly captured international attention, yet it has since become a bit of a Brussels mystery, vanishing multiple times, only to reappear a few years later somewhere completely different.

Its collection was originally housed in a room above the De Dolle Mol, a feminist-anarchist cafe on a cobbled backstreet set just back from Grand Place. Curious visitors would come from as far as Asia and South America to peer at pieces – many of which are signed – before heading off to sip a Jupiler beer among Brussels’ Bohemian far-Left in the bar below.

Letizia Ortiz of Spain's intimates. Credit: Ludovic Harrys

Its notoriety even attracted thieves. In 2014 the underwear of Yvan Mayeur, mayor of Brussels between 2013 and 2017, was stolen from the museum. “Maybe I was naive. I thought my museum would make people laugh but I find that even my exhibits are not safe. What should I do? Install security cameras?,” Bucquoy said at the time, before offering to buy a beer for the robber if the politician’s pants were returned unhurt. They were, although the thief never claimed their beer.

However fame and art heists were not enough to save the collection. The lease on the De Dolle Mol café expired in 2015 and the Flemish Community cut off funding, forcing Bucquoy to find a new home for his pants.

The museum secured a temporary base in the restaurant Chez Claude in Rue de Flandre before it was decided the collection would be moved to the town of Lessines, the birthplace of Belgian surrealist artist René Magritte. This was to be its new permanent residence.

Grandiose plans were laid: the collection was to occupy one of the oldest buildings in the town and new exhibits were to be added, including, according to local rumours, boxers and briefs worn by singer Stromae and chess grandmaster Garry Kasparov. But these did not materialise and the pants continued their vagabond existence, reappearing in an antique shop in the Marolles. Currently the collection can be found in Attitude, a contemporary art gallery on Brussels’ Rue Haute.

The enigmatic Bucquoy

As the founder of one of Belgium’s slipperiest and most elusive museums, it’s no surprise that Bucquoy himself is something of an enigma. He has worked across film, comics, painting and sculpture.

The linking thread of his oeuvre is the impossibility of explaining whether it is comedy, cutting political commentary, pure surrealism or a mixture of all of them. His works, which include the comic La Vie Sexuelle de Tintin, have caused scandal due to their irreverent representation of national heroes and the Belgian monarchy.

Jan Bucquoy, the anarchist creator of the Underwear Museum.

Yet underpants are far from being the strangest subject matter for a Brussels museum. There is a gallery of “spontaneous” art, the only museum in the world devoted to fencing as an Olympic sport and even a street lamp museum: a strip of pavement along Rue Emile Delva illuminated by 20 different lampposts which showcase the evolution of street lighting in Brussels.

There was also the Penguin Museum: an array of around 3,500 pieces of memorabilia dedicated to the flightless bird and displayed in the home of its collector, Belgian pensioner Alfred David. Known as Monsieur Pingouin (Mr Penguin), David would often don a hooded black-and-white bird suit while telling visitors of his plans to be buried in Antarctica alongside his compatriots. His obsession with penguins began in 1968 when he was involved in a car crash that permanently damaged his hip and left him with a strange waddle, explaining his nickname. Eventually the collection was donated to a local football team and the museum disappeared.

Brussels, capital of quirk

Much of Brussels’ appeal is the quirkiness of its people and museums, says Jeroen Roppe of Visit Brussels, the city’s tourism office. “It is known as the capital of surrealism and so attracts those interested in visiting or creating these kinds of unusual places,” he adds. “Years ago Brussels had a reputation of being quite grey and boring – but not anymore.”

In 2019 the Washington Post described Brussels as the epicentre of Europe’s contemporary art scene. “Travellers have realised this and the number of people coming to Brussels for a city break has increased enormously over the past few years,” Roppe says.

In fact, creative little Brussels has one of the highest ratios of museums per citizen of any city in the world. There are 93 museums for its around two million strong population, according to an index by the World Cities Culture Forum. Whereas New York, which has around 10 times as many residents, has just 47 more museums (140 in total). Madrid, the index suggests, has just 59 museums and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.5 million.

However the future of all these institutions has been thrown into jeopardy by coronavirus. Both UNESCO and the International Council of Museums have predicted that 13% of museums around the globe could close permanently as a result of the pandemic.

Collections such as the Musée du Slip, which are small and have a cult rather than general appeal, are some of the most at risk. They are less likely to receive government support. So it is up to the public to decide whether to get back into galleries, and keep these off-beat institutions as part of their cultural fabric, or watch them vanish forever.