A warring family holds the keys to an elusive Belgian masterpiece, but they want to keep it to themselves. What's the story behind the magnificent Stoclet Palace?

I saw it for the first time through a tram window. It was a severe modern building on Avenue de Tervuren with a fiercely clipped hedge at the front and a geometrical tower decorated with four giant nude males. The building stood out next to the avenue’s traditional eclectic mansions. It looked austere. Even forbidding.

I got off the tram at the next stop to have a better look. The marble façade was streaked with pollution from traffic on the busy avenue. The copper statues had corroded. It looked like it could be a neglected municipal building. Not as beautiful as Victor Horta’s Hôtel Solvay on Avenue Louise. And yet definitely intriguing.

It’s easy to find out the building’s history. Just look up Palais Stoclet in any guide to modern architecture. Emerging between the Art Nouveau and Art Deco periods, the building was commissioned in 1905 by the millionaire Belgian engineer and banker Adolphe Stoclet. He came from a family that had grown rich in the 19th century building railways. His wife Suzanne was the daughter of the art dealer Arthur Stevens. They formed a formidable Belgian couple with a shared passion for art and architecture.

While living in Vienna, the young couple went on long walks looking at fin-de-siècle architecture. That’s how they discovered the architect Josef Hoffmann, a founding member of the radical Wiener Werkstätte group. Hoffmann embraced the ideal of the Gesamtkunstwerk, or total work of art, in which architecture, sculpture and art formed part of a single composition.

Stoclet asked Hoffman to design a sumptuous villa. Initially, it was to be built in Vienna’s Hohe Warte district, but he suddenly had to relocate to Brussels after the death of his father. He acquired a large plot of building land on the beautiful Avenue de Tervuren that Leopold II had just built. His aim was to create a shrine to art and a declaration of love addressed to Suzanne. A Belgian Taj Mahal, you might call it.

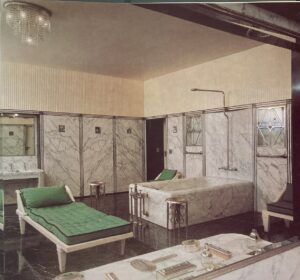

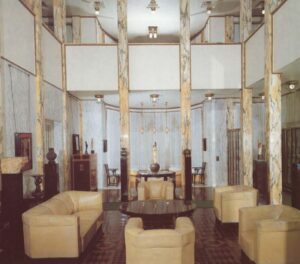

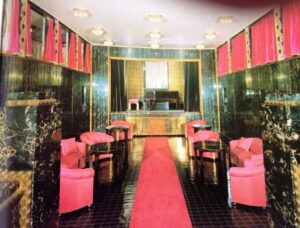

Hoffmann had been desperately looking for a wealthy client who could help him realise the perfect Gezamtkunstwerk. Stoclet was prepared to pay whatever it took. Hoffmann drew up an ambitious plan for a three-story house clad in white Norwegian marble. He added a stair tower decorated with four copper statues by the sculptor Frantz Metzner. Gustav Klimt was persuaded to create a huge frieze for the dining room. Artists and craftsmen were recruited to design every detail, including the light fittings, door handles and cutlery. Along with the clipped hedges in the garden. And even the silver toilet fittings. Everything.

It took much longer than expected to build and cost unbelievable millions. But Stoclet remained calm. He knew he was getting a unique masterpiece. A new architecture for a new century conceived in the hothouse atmosphere of fin-de-siècle Vienna.

The couple finally moved into the palace in the spring of 1911 although some of the furniture would only arrive later. They blended in perfectly. Suzanne chose the flowers to decorate the house in a single colour, while Adolphe would always select a tie to match his wife’s dress.

They invited some of the finest avant-garde artists and architects of the period to visit the house, including Jean Cocteau, Serge Diaghilev and Robert Mallet-Stevens. The philosopher Walter Benjamin described the palace as a “dream house”.

After the couple died – Adolphe in 1949 and Suzanne in 1960 – the palace was inherited by Adolphe’s son Jacques. His aristocratic wife, Baroness Anny Stoclet, preserved the artistic ambience, inviting celebrated musicians to perform in the music room.

When Anny died in 2002, the property passed to her four daughters, Catherine, Nèle, Dominique and Aude. They had all grown up in the house and described it as “une maison enchantée”, a fairy-tale house. Yet none of the sisters elected to live there. The problem is that it isn’t an easy place to live.

The Palais Stoclet has remained empty ever since, apart from a solitary caretaker. The four elusive sisters strictly refuse to allow anyone to see inside. Over the years, it has become an intriguing story of reclusive wealth and family feud, like the TV series Succession relocated to the Brussels suburbs.

Forbidden palace

The editor recently decided it was worth a story. “You could ask the family to look around, or even ring the doorbell,” he slyly suggested. And so, once more, I set off on tram 44 to dig out a story.

I had barely stepped off the tram when the plan fell apart. There was no doorbell. No name. Nothing except the number 279. The bronze warrior figure above the entrance porch added to the impression that this was a fortress, not a home.

I had expected something more, given the house had been listed by UNESCO in 2009 as a world heritage site. “Bearing testimony to artistic renewal in European architecture, the house retains a high level of integrity, both externally and internally as it retains most of its original fixtures and furnishings,” the UNESCO report reads. “A veritable icon of the birth of modernism and its quest for values, its state of preservation and conservation are remarkable,” UNESCO argues to justify its inclusion on the prestigious list.

Normally, the Brussels Region takes considerable pride in its architectural heritage. It will put up an information sign in four languages if the house is interesting. But you could easily walk straight past the Palais Stoclet without realising its importance.

A tiny number of people have seen inside the building, while a far greater number have stood on the pavement outside cursing the owners. You can read some of the responses on Tripadvisor, where most of the 43 comments express disappointment.

The lucky few who have been admitted don’t reveal how they did it. A couple from Australia note that they “had the pleasure to have been invited to the Palais in the 1990s while Baroness Stoclet was living in this fantastic home.” Another visitor from Peru “had a short private visit of this outstanding villa.”

Oh well, I thought, I can always look at photos of the interior. Only I couldn’t find many. It appears those who are allowed inside are told that photos are banned. The rare images on the internet are grainy black-and-white photos taken many decades ago. They just add to the mystery of the Stoclet Palace.

The city has tried many times to persuade the family to open the house to the public. One of the earliest attempts was back in 1987 when the Europalia arts festival focused on Austria. But the family flatly refused to grant access to anyone. The festival had to make do with a scale model of the house and a postage stamp showing a detail of the Klimt frieze.

The family’s stubborn refusal to cooperate has frequently brought them into conflict with the Belgian authorities. After the death of Adolphe and Suzanne, the Stoclet’s exceptional art collection passed to the heirs. The works included a tiny painting of the Madonna and Child by Duccio which the heirs sold to the Metropolitan Museum of Art for a record $56 million.

The Belgian authorities immediately panicked at the thought of the precious furnishings being sold off and in 2011 Brussels Region brought a legal action to protect the unique Wiener Werkstätte interior. Three of the sisters appealed to the Council of State to stop the ruling. But Aude defended the decision, arguing that the house and furnishings should be preserved as a total work of art, managed by a foundation. The three sisters lost the case, which means the unique Wiener Werkstätte furnishings cannot leave the building. Everything remains exactly as it was in 1911 when the Stoclets moved in.

Eerie mystique

But still, no one was permitted to enter the house. It has remained deserted since 2002 apart from the solitary caretaker. Catherine died in 2011, and Nèle one year later, leaving the house in the hands of two sisters and several great-grandchildren.

A fresh appeal to the owners was launched in 2016 by Benoît Cerexhe, the mayor of Woluwe-Saint-Pierre. He pointed out that the family were receiving grants of up to 80 percent of the cost of renovation work. Surely the public should be allowed inside since they have funded the work through their taxes. “It's a real pity it's closed now, all the more because it's just standing there, empty,” Cerexhe said at the time. “I often get requests from people wishing to visit the mansion but have to turn them down. You often see people taking out their camera at the front fence.” Yet Cerexhe failed to convince the heirs.

In May 2021, Anne-Charlotte d'Ursel, a countess politician with the French-speaking liberal party, asked about access to the Palais Stoclet in a session of the Brussels Parliament. Pascal Smet, the Brussels state secretary for heritage, replied that most of the heirs were still opposed to opening up the palace because it was such a fragile building. “I can’t force them to open their house,” Smet explained.

Smet had some good news to report. He had instructed his staff to look into the possibility of creating a virtual 3-D reconstruction, similar to one that was created for Victor Horta’s demolished Maison du Peuple. But it remains up to the heirs to decide.

It’s frustrating. Of course, it is. We want to look inside, not just stand in the street peering over the hedge. It’s especially irritating when we know that no one even lives there. It could be an extraordinary world heritage site, like Frank Lloyd Wright’s Falling Waters or the Rietveld-Schröder House in Utrecht. If only the heirs would agree.

And yet the Palais Stoclet was always meant to be a private paradise, a retreat from the world. Maybe it should be left as a building you glimpse through a tram window, a mysterious relic of a lost age.