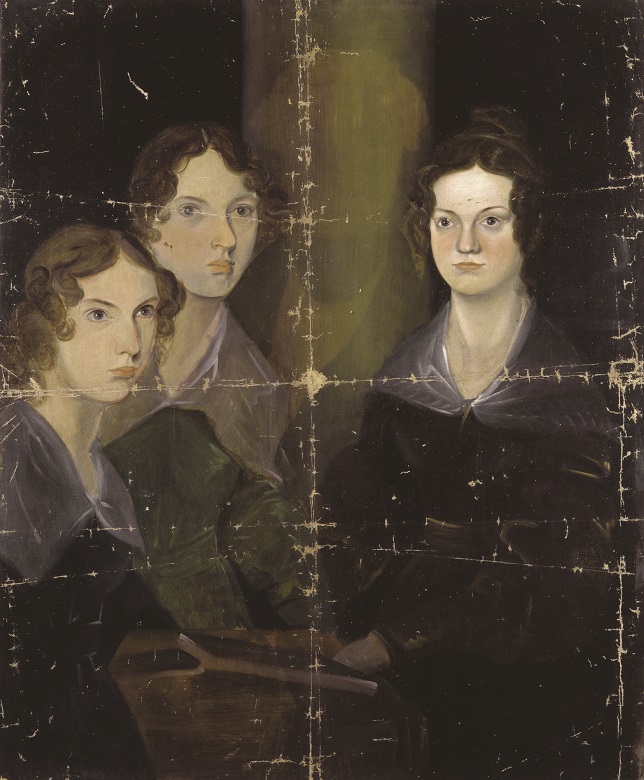

Emily and Charlotte Brontë are icons of English literature, their passionate, eternal love stories among the most-read novels of the 19th century. Yet these Yorkshire-born novelists, known for their evocations of northern English landscapes, spent a vital chapter of their lives in Belgium.

The Brontë sisters are among the best-loved writers in the English language, whose pioneering novels in the mid-19th century are still read voraciously today. Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre, Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights and Anne Brontë’s The Tenant of Wildfell Hall can be all found in decent bookshops, libraries and school reading lists. Even those who have not read their books might have seen the movie adaptions, like the 1939 Wuthering Heights with Laurence Olivier and Merle Oberon as Heathcliff and Cathy, or Jane Eyre, adapted in 1943 with Joan Fontaine and Orson Welles, and in 2011 with Mia Wasikowska and Michael Fassbender.

The place the Brontë family is invariably associated with is the Yorkshire moors, the setting both for Wuthering Heights and for their own lives. Haworth, the Yorkshire village where the sisters spent much of their short lives, is a magnet for tourists eager to see this setting with their own eyes. Interest in the family that created some of the world’s most passionate love stories has turned Haworth’s Brontë connection into an industry and the village, some complain, into a theme park. The Brontë Parsonage Museum is a literary shrine drawing fans from all over the globe, so much so that today the footpath signs on the moors include directions in Japanese.

Rather less well known as a Brontë shrine is the city whose connection to the family is so little trumpeted you can spend all your life there without hearing about it: Brussels.

The Belgian capital barely acknowledges its link with the two most famous Brontë sisters, Charlotte and Emily. A plaque commemorates their stay here in 1842-43, at a girls’ boarding school called the Pensionnat Heger, which stood on the site now occupied by Bozar, the Centre for Fine Arts. However, it is placed high up near Bozar’s entrance: most concertgoers pouring through the doors are oblivious of it, as are most tourists.

Unsung heroines

It is a pity the city is so silent about its Brontë link. Visitors are unlikely to have heard about the connection before they come. Mention the Brontës and how many people picture the sisters strolling on the boulevards in Brussels?

Yet they did – and so do some of their fictional characters. Although it is not hard to see why the connection can be missed. Charlotte wrote two novels set in Brussels and based on her time in the city: her first, The Professor, which was not published until 1857, two years after her death; and her fourth and last, Villette (1853). But neither were bestsellers like Jane Eyre. Many literary pundits rate Villette as her most interesting book, but, sadly, no feature film has ever been made about its heroine Lucy Snowe, a sharply observant expat experiencing loneliness and frustration as a teacher at a pensionnat.

That Charlotte Brontë’s link with Brussels is not better known is partly her own doing: she underplayed the location. In The Professor, a tale of a young English teacher who falls in love with one of his pupils, the setting is explicitly identified as Brussels. But in Villette, a more closely autobiographical novel, the city where Charlotte herself fell in love is disguised under a fictional name: the ‘continental capital’ she calls ‘Villette’ is Brussels in all but name.

Charlotte Brontë

Why the disguise? One reason, given some of her views on Belgium, may have been a wish to spare the feelings of Belgian readers. In Villette, Belgium becomes ‘Labassecour’ (the ‘farmyard’ or ‘barnyard’) and the ‘Labassecouriens’ are depicted as shallow and deceitful.

Lucy Snowe subjects the inhabitants of her host country to mocking scrutiny, criticising their religion in particular – Charlotte was the daughter of a Protestant clergyman. However, she is keenly appreciative of other aspects of continental life such as the food, the fashions, and the splendour of ‘Villette’s neo-classical Haute Ville. An even stronger reason for concealment was the ease with which Charlotte’s fictional pensionnat could have been identified as the Pensionnat Heger. The book revealed too much about her emotions at the real-life school.

Pensionnat Heger

What brought Charlotte and Emily to Brussels in 1842 at the ages of 25 and 23 respectively, some years before achieving fame as novelists, was ambition and the wish for higher education. Charlotte was the eldest and most ambitious of the three sisters: the project was her baby. The sisters planned to start their own school in England. Perfecting their French and other foreign languages would improve their chances of attracting pupils.

Emily Brontë

An educational stay on ‘the continent’ was an expensive venture for the cash-strapped daughters of a poor Irish clergymen, and an aunt was persuaded to help fund the trip. Charlotte wrote to her excitedly:

“I could acquire a thorough familiarity with French, and even get a dash of German…If this advantage were allowed us, it would be the making of us for life. Papa will perhaps think it a wild and ambitious scheme; but who ever rose in the world without ambition? When he left Ireland to go to Cambridge University, he was as ambitious as I am now. I want us all to go on. I know we have talents, and I want them to be turned to account.”

Promised land?

Charlotte opted for the Belgian capital, which she called her “promised land”, because a friend of hers was studying there – and it was inexpensive: “Living there is little more than half as dear as it is in England, and the facilities for education are equal or superior to any other place in Europe.”

A clergyman contact recommended the Pensionnat Heger in Rue d’Isabelle, near Place Royale and the Park, where the two sisters could board, attend classes and do some teaching to help pay their expenses. Charlotte taught English classes. Emily, who was a keen musician, gave piano lessons to the younger pupils.

Academically the European adventure was a success. Although much older than the other demoiselles, the sisters sat diligently soaking up the French language in the classrooms of the Pensionnat, run under the benign direction of Madame Heger and her husband. The volatile, charismatic Constantin Heger, an inspiring teacher, was 32 (his wife was four years older) and the couple had a rapidly growing family.

Monsieur Heger gave the two girls private tuition in French language and literature, setting them essays (‘devoirs’) to write. These have survived and been published, alongside English translations, with Heger’s corrections and comments.

At times he may have been taken aback by his two pupils’ handling of their topics. Charlotte turned a composition on Napoleon into a eulogy of her hero Wellington. Emily, in an essay on cats, argued that if they are cruel and self-interested, then they exactly resemble human beings.

The future creator of Wuthering Heights kicked against Heger’s guidance, but for Charlotte he was a fount of support and intellectual stimulation. His French classes became the highlight of her week. When she decided to stay on in Brussels for a second year, this time without Emily who was desperately homesick for the moors, it was the thought of Monsieur Heger that pulled her back to the Pensionnat after the Christmas break.

The Heger family

But that second year did not go as well as the first. She saw less and less of her tutor and suspected his wife of keeping them apart out of jealousy. Years later she took revenge on Madame by portraying her as the hypocritical school director in Villette. The staunchly Protestant Charlotte became so unhappy that one day in September 1843 she sought consolation by confessing to a Catholic priest at the Cathedral of St Gudule, an episode recounted in Villette. She left Brussels at the end of the year.

Unrequited affections

Back in Haworth, she tried to revive the connection with Heger, writing him letters in French. Unemployed and depressed, she felt life was passing her by and longed for the encouragement he gave her in the early days in Brussels. Heger answered occasionally with bracing advice, but she begged him for more letters. As her tone became more and more overwrought (“Day and night I find neither rest nor peace. If I sleep I’m disturbed by tormenting dreams in which I see you”), he instructed her to write less often and with more restraint. Then he stopped replying.

At some stage Heger tore up her letters. We know this because, astonishingly, some of these shredded letters (his to her were not preserved) have survived and can be viewed today, with the jagged pieces sewn or gummed together again. Heger’s children donated them to the British Museum in 1913 and in the same year Charlotte’s outpourings to her tutor were published for the first time, causing a stir. According to Heger’s daughter, Monsieur tore the letters up and threw them away. But Madame repaired and kept them as proof that her husband had not behaved inappropriately with his fiery pupil.

Not long after Heger fell silent, Charlotte recovered her spirits enough to write Jane Eyre, which brought her almost overnight fame (happily for literature, the sisters’ project of opening a school came to nothing and they turned to novel-writing instead). But Heger and Brussels were not forgotten.

A decade after leaving the city she revisited it in imagination in Villette and brought her former tutor vividly to life as Monsieur Paul, the fellow teacher Lucy Snowe loves. Charlotte had already put something of Heger into Mr Rochester, the hero of Jane Eyre, but Monsieur Paul in Villette is a fuller and less romanticised portrayal of her Belgian schoolmaster. Charlotte clearly enjoys Lucy’s and Paul’s cultural clashes along the bumpy road to understanding. Fortunately for Lucy, in the fictional Pensionnat her hero returns her feelings and is not a married man with six children. But even so the pair are denied a happy ending at the close of this dark and haunting novel.

Brioches and pistolets

What did Charlotte think of Belgium, which had only been an independent country for just over a decade when she arrived? Lucy may be irritatingly critical of ‘foreigners’ not fortunate enough to be English and Protestant like herself, but she’s an entertaining observer of every aspect of life in her host country, from her delight in brioches and pistolets to her fascination with Catholic confession rituals.

Charlotte retained a photographic memory of the city that had marked her so deeply. Some of what she describes has vanished. Rue d’Isabelle, built in the 17th century by the Archduchess Isabella to provide the royal household with a route to the Cathedral, was razed in the first decade of the 20th century along with the surrounding neighbourhood to make way for construction projects such as the Central Station and Mont des Arts. Victor Horta’s Art Deco Palais des Beaux-Arts was built on the site of the school.

Other city landmarks described by Charlotte in her Brussels novels are still standing. We can walk in the park where Lucy, under the influence of an opiate, wanders in a hallucinatory scene during a night-time fête commemorating the Labassecourien (for which read, Belgian) Revolution. We can visit the Chapelle Royale off Place Royale where the sisters worshipped, as did the Protestant Leopold I, and pause in Rue Royale to look up at the statue of General Belliard, the French ambassador who helped to negotiate Belgium’s independence in the 1830 Revolution. That rising was still a recent memory in the Brontës’ time and Charlotte mentions the monument to the fallen patriots in Place des Martyrs.

So, not all the Brontë-era Brussels has disappeared. And around Bozar, if you look hard, you can find fragments of the old streets the Brontës walked on that have miraculously survived: Rue Villa Hermosa and Rue Terarken. In their time, a steep narrow flight of steps, behind the Belliard statue, led down to Rue d’Isabelle (a more modern flight leads down to Rue Baron Horta today). In imagination, I’ve often descended those vanished steps into the Brontës’ neighbourhood in Brussels, which I’ve reconstructed in my mind from old photos and from descriptions in The Professor and Villette.

Old steps

At the end of the truncated cul-de-sac of Rue Terarken, which stops abruptly at a delivery entrance to Bozar, a thrill lies in wait for those with the sharp eyes of a Lucy Snowe. On the wall next to this back entrance is a replica of the round blue literary plaques seen on writers’ houses all over Britain. Like the one by Bozar’s front entrance, it commemorates the Brontës’ stay. But this plaque is unofficial, placed in 2004 by a Dutch fan who wanted to give the Brontës a memorial in one of the streets that existed in their time.

Steps today

Shortly after, in 2006, I founded the Brussels Brontë Group with fellow Brontë admirers to promote the literary link. We have organised guided walks and numerous events to celebrate the connection and over the years we’ve approached city authorities with ideas for ways of making it more visible. But our proposals for a major exhibition or a statue have yet to be picked up. In Haworth, everything yells, ‘The Brontës lived here!’. In Brussels, the passage of the sisters through the city can seem like a secret only known to a few.

There’s a charm in that, of course. Because if you’re one of those chosen few, you’ll find yourself, one day, in a cobbled street so tiny hardly anyone knows it’s there, gazing at a home-made plaque and marvelling at the thought that the Brontë sisters trod those cobbles.

How Brussels became Villette

“Villette! Villette! Have you read it? It is a still more wonderful book than Jane Eyre. There is something almost preternatural in its power.” This was the verdict of the great Victorian novelist George Eliot on reading Charlotte Brontë’s last novel, published in 1853.

Not all readers will find it as romantically appealing as Charlotte’s better-known 1847 classic Jane Eyre. But many will be haunted by the tale of Lucy Snowe, an English teacher struggling to make a life for herself in a strange city. While Brussels is never named as such in the book, the city of ‘Villette’ is so obviously the Belgian capital Charlotte knew in 1842-43 that the first French translation of the novel was published under the title La Maîtresse d’anglais ou le Pensionnat de Bruxelles.

There are parallels between Lucy Snowe and the better-known Jane Eyre. Both, like Charlotte herself, are poor, plain and determined to earn their own living, since their lack of wealth and beauty makes it unlikely that they will find love and marriage. In both novels the heroine falls in love with an older man she meets through her work. Jane Eyre ends happily; Jane marries her boss, Mr Rochester, and the story became the template for countless romances of poor girls marrying rich, brooding older men.

There is no fairy-tale happy ending for 23-year-old Lucy Snowe and her colleague Monsieur Paul in Villette, in many ways a darker, more complex, more interesting and more modern book than Jane Eyre. In a novel that is psychoanalytical before psychoanalysis was a concept, Charlotte gives us a study of depression, frustration and loneliness and the limited choices facing single women in her time, but also a lively, often funny account of an expat adjusting to a new culture.

The romance that blossoms in the classrooms of the Pensionnat between the proudly Protestant Lucy and the devoutly Catholic Monsieur Paul may seem unlikely at first. But, as in the relationship between Rochester and Jane, Monsieur Paul, despite his faults, is the one person who can see Lucy as she really is and love her for what she is, in spite of her own faults.