“Why not have a look, I’m sure you’ll find a few stories in them.” The editor is pointing at two humongous, 99-year-old tomes he’s acquired at the Jeu de Balle flea market in Brussels.

The covers are worn but the title is legible: L’Album de la Guerre 1914-1919, volumes 1 and 2. I turn a few pages. The text is in French. On the upside, the books are lavishly illustrated.

I pick one up. It’s heavy. Over six kilograms. The other volume is just as weighty. Today they’d most likely be called coffee-table books, if anyone could find a coffee table strong enough. The boss is determined, however, and a quarter of an hour later I’m hugging them in my arms to the metro, cursing every step. I stop at my wife’s office for sympathy. She has a suitcase with wheels. Result.

Later, I’m glad the editor persuaded me. The books are a treasure trove of facts about the events and people, many long forgotten, that shaped the Great War. Produced by popular French news weekly L’Illustration and based on its coverage during the conflict, L’Album de la Guerre chronologically covers the story of the war across its many theatres, from the “supreme defence” of Antwerp to the bloodbaths of Ypres, the Somme and Verdun, to Salonika, Serbia, German South-West Africa, Hejaz, Russia, and all points between and beyond.

The level of detail is immense to the point of being almost overwhelming. A few chapters would fill a whole issue of The Brussels Times Magazine. The images are, in some cases, uncomfortably graphic by modern standards. Were it published today, L’Album de la Guerre would likely carry a warning that it contains scenes that some readers may find distressing.

The authors do not pretend to offer an unbiased account. It’s crystal clear who are the heroes and villains. The French poilus, British Tommies and Belgian Jasses are unmistakably the good guys. So too the Doughboys when the United States finally enters the war, after a lobbying blitz by Britain and France. Marshal Joseph Joffe, the hero of The Marne, gets credit for swaying the waverers. He is cheered to the rafters in the US Senate when he succinctly declares: “I don’t speak English, vive les États-Unis”.

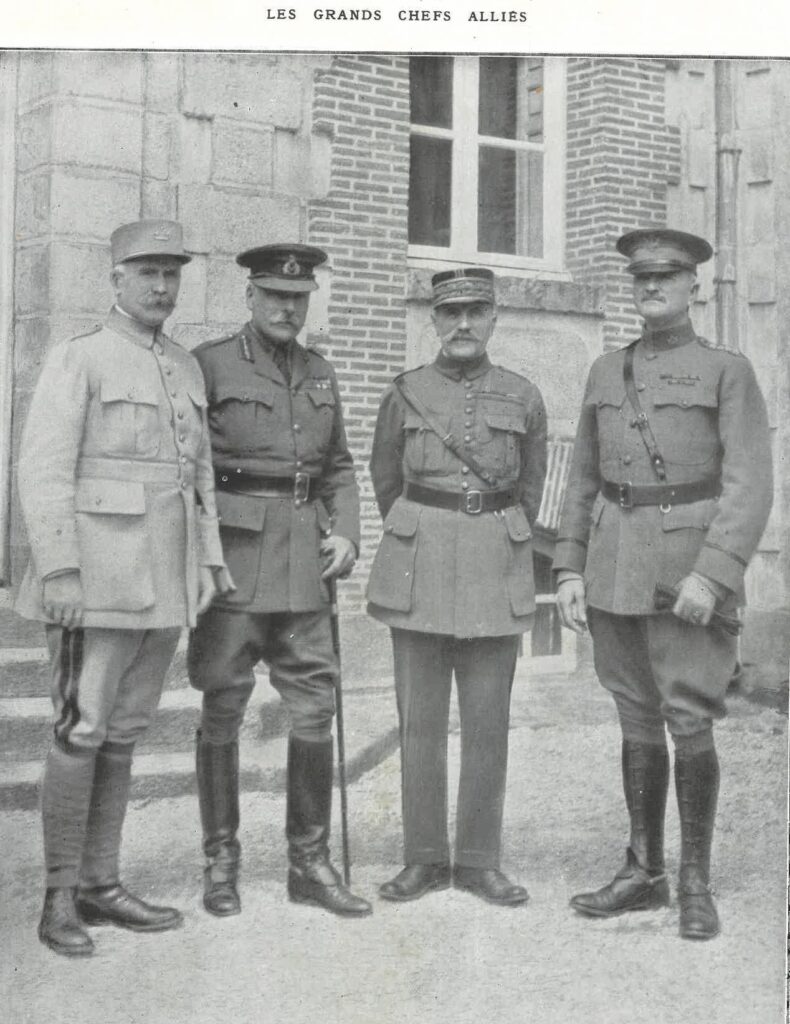

Allied commanders General Philippe Pétain, Field Marshal Douglas Haig, Marshal Ferdinand Foch and General John Pershing, at the château de Bombon, south-east of Paris, on August 23

The coverage of the short-lived Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, under which Russia gave up nearly all of Ukraine and ceded Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia to German control in March 1918, is especially apposite in light of recent events. It’s hard not to be unmoved by an image of the bullet-scarred basement in Yekaterinburg in which Russian Tsar Nicholas II, his wife, children and staff, were mercilessly mown down in July 1918.

The story is unsurprisingly mostly told from a French point of view with, frustratingly but understandably, next to no information about what happened after the events it describes. What follows are excerpts from a Belgian angle, with additional information and context about the key protagonists – and how they fared after the conflict.

The Soldier King and his German Queen

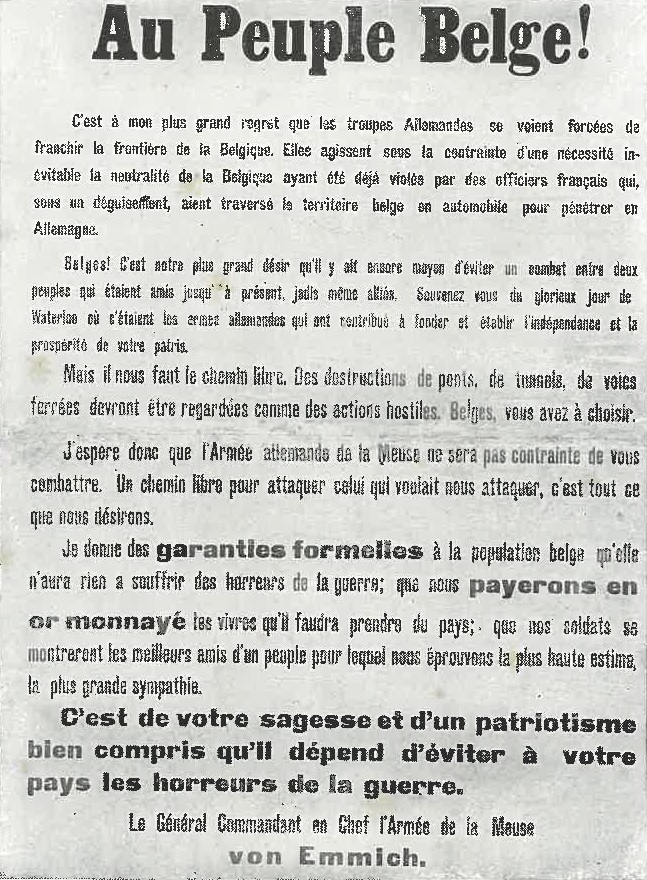

The album is full of heartfelt tributes to “heroic and martyred” Belgium, personified by its Soldier King, Albert I. On the eve of war, a German proclamation demands free passage through the country, urging the people to “remember the glorious day of Waterloo where German arms contributed to the founding of Belgium, its independence and prosperity.” The notice, signed by General Otto von Emmich, backfires. For L’Illustration, it serves only to unite a country “previously divided along social, political and religious lines.”

German proclamation demanding free passage through Belgium

The newspaper praises the King’s “staunch resistance” and “male energy” when he appears at the Belgian Parliament on August 4, 1914, and asks deputies and senators: “Are you unwavering in your determination to keep the sacred heritage of our ancestors intact?” “Yes, yes, yes,” they reply.

From the first shots, Albert is at the heart of his men, leading by example. When shrapnel explodes near him, an aide-de-camp urges the King to move somewhere safer. Albert stands firm, responding: “You wouldn’t want your leader moving away from danger when he’s sending his men to face the enemy’s bullets, would you?”

The Germans head towards Brussels, with heavy fighting around Hofstade and Schiplaken. Their attacks force locals to build trenches and carry out savage reprisals against alleged guerilla francs-tireurs.

Lieutenant Charles de Gaulle, 24, is badly wounded as the French try to hold Dinant. The attackers massacre hundreds of civilians there, as well as at Tamines and other towns in the “Rape of Belgium”. The university library in Leuven, with its priceless collection, is razed to the ground.

The King, meanwhile, faces a potential minefield close to home. His wife, Queen Elisabeth, is German – indeed, she is a duchess of Bavaria by birth.

But any fears of divided loyalties are immediately swept away. “There is not one piece of her heart that doesn’t beat with and for Belgium,” L’Illustration reports. The album is full of heartfelt tributes to “heroic and martyred” Belgium, personified by its Soldier King, Albert I. at the advent of the Cold War. The newspaper is moved by the Queen’s stoicism as “she goes from town to town, camp to camp, trench to trench, consoling the living and the dying”.

Zita, the last Empress

L’Album de la Guerre begins with the double killing that triggers the chain of events that leads to world war just over a month later: the Sarajevo assassination on June 28, 1914, of Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie by 19-year-old Bosnian Serb Gavrilo Princip. Ferdinand is the nephew and heir of Franz Joseph, Emperor of Austria and King of Hungary. When Franz Joseph dies aged 86 in November 1916, the two thrones instead pass to his great-nephew, Charles I.

The new Emperor, Empress Zita and their four-year-old son, Crown Prince Otto, are pictured leading mourners at Franz Joseph’s funeral in Vienna. Two of Zita’s brothers, Sixtus and Xavier, are officers in the Belgian Army, while three, Elias, Félix and René, are on the Austro-Hungarian side. Charles asks Sixtus to launch secret peace overtures with the French. The talks fail and the young Emperor’s position is seriously weakened when France’s Prime Minister, Georges Clemenceau, reveals compromising letters signed by him.

Emperor Charles, Empress Zita and Crown Prince Otto at the funeral of Franz Joseph

After the Armistice, the imperial family are spirited to Switzerland by British troops on the orders of King George V, who fears the worst after the 1918 murder of his cousin, Russia’s Tsar Nicholas II and his family, by the Bolsheviks.

After failed attempts to win back the Hungarian Crown, Charles and Zita move to Madeira, where the former Emperor dies, aged just 34, from pneumonia. Zita and her children move to Spain for six years, then live in Belgium for a decade at the Kasteel Ter Ham in Steenokkerzeel, close to Brussels Airport.

The family escape to the US after the German invasion in 1940, returning to Europe in the early 50s. Zita dies in Switzerland, aged 96. Former Crown Prince Otto von Hapsburg, who studies at Leuven and serves as a member of the European Parliament from 1979 until 1999, dies on 4 July 2011, aged 98.

Water torture

The album tells the extraordinary story behind the flooding of the Yser plain which halts the enemy’s advance across West Flanders. The idea comes from Emeric Feys, a judge from Veurne, who uncovers documents proving that the same tactics were successfully used to frustrate a previous invading army – the French – in 1793. He shows them to General Félix Wielemans, Deputy Chief of the Belgian General Staff, who is eager to relieve the pressure on his besieged troops.

Belgian hero Karel Cogge

Karel Cogge, supervisor at the local water board, Noordwatering van Veurne (NWV), confirms that it is possible to submerge a strip of land between Nieuwpoort and Diksmuide – a distance of 15km – but it means opening the Noordvaart sluice gates which are right under the enemy’s nose.

On the night of October 29-30, 1914, chief lock-keeper Hendrik Geeraert and a small group of Belgian soldiers slip across no man’s land and manage to reach the gates unseen. They crank them open as slowly and quietly as possible to avoid alerting the Germans. The saboteurs return under cover of darkness to repeat the exercise on subsequent days until the whole plain is gradually turned into impassable marshland.

For the rest of the war, it is virtually impossible for the enemy to move their artillery on the Yser front. As for Cogge and Geeraert, they become national heroes and are awarded the Order of Leopold. A bust commemorating Cogge is erected in Veurne in 1927, five years after his death.

Battle for Ypres and first gas attack

The Ypres Salient, strategically important as a gateway to the Channel ports, is the scene of bitter fighting throughout the war. After the First Battle of Ypres (October-November 1914) ends in a stalemate, the album reports on the launch of a new offensive on April 22, 1915, between Langemarck and Steenstraete, in which the enemy uses poison gas for the first time. Allied soldiers see the three-metre green cloud coming towards them “like a moving wall” and assume it is just smoke but fall suffocating to the ground.

In the absence of gasmasks, the troops initially resort to wearing spectacles and improvised mouth coverings – similar to Covid face-masks – in a hopeless bid to protect themselves. The fighting around Ypres results in over a million casualties during the war and leaves the medieval town in ruins.

Magnificent men and their flying machines

L’Album de la Guerre devotes an entire chapter to the dashing aviation aces whose battles in the skies over Flanders, fought in primitive flying machines, capture the public imagination.

Belgian pilots receive visit from Queen Elisabeth

Lieutenant Rex Warneford is the first airman to bring down a Zeppelin in flight. On the night of June 6-7, 1915, he is aboard his Morane-Saulnier reconnaissance plane when he spots the enemy airship near Ostend. The 23-year-old British pilot gives chase and, despite coming under defensive fire, manages to fly his aircraft above the Zeppelin. He drops a cluster of Hale bombs. The last is bang on target, instantly setting it alight.

Zeppelin LZ 37 crashes in a ball of flame on a convent at Sint-Amandsberg near Ghent, killing all but one of its nine-man crew, as well as a nun and a nine-year-old girl caught in the debris. The explosion overturns Warneford’s plane and stalls the engine. Forced to land behind enemy lines, he manages to repair and restart the machine before the Germans capture him. Yelling “Give my regards to the Kaiser!”, he takes off and returns to base.

Warneford’s exploit earns him the British Victoria Cross, the highest award for valour in the face of the enemy. On June 17, General (later Marshal) Joseph Joffre presents him with the Legion d’Honneur at an aerodrome near Versailles. After a celebratory lunch, Warneford takes off in a Farman biplane with a passenger, US journalist Henry Beach Needham. As he climbs, the right-hand wings collapse and the aircraft plummets to the ground. Needham dies instantly and Warneford succumbs to his injuries en route to hospital. Warneford’s funeral in London is attended by thousands.

Much coverage is dedicated to France’s popular pilot, Sgt (later Capitaine) Georges Guynemer of the elite escadrille des cigognes (stork squadron), commanded by Major Antonin Brocard. Guynemer has 54 victories to his name, including four in a single day, when he is killed at the age of 22 after a dogfight near Poelkapelle on September 11, 1917. A memorial to Guynemer, topped by a bronze stork, is erected in the village in 1923. Brocard survives the war and is recalled in 1939 as a pilot trainer. He dies in 1950.

French ace Georges Guynemer

Brussels-born ace Willy Coppens is credited with 37 victories against planes and artillery observation balloons. He flies a royal blue Hanriot and is known as “the Blue Devil”. On October 14, 1918, he is badly wounded and forced to crash-land near Diksmuide. He survives but his left leg is amputated in hospital. After the war, King Albert makes him a baron and Coppens serves as military attaché to Britain and France. He dies in Berchem, aged 94, in 1986.

However, the most famous war ace is completely overlooked by L’Album de la Guerre. Germany’s Manfred von Richthofen, the “Red Baron”, credited with 80 victories, is fatally wounded near Vaux-sur-Somme on April 21, 1918. Who fired the shot that brought him down is hotly disputed to this day.

Raid on Zeebrugge

The art of spin is nothing new. As with Dunkirk 22 years later, the British prove how adept they are at snatching a propaganda victory from the jaws of defeat after a botched naval raid at Zeebrugge on April 22-23, 1918. The target of the daring assault, planned by Vice-Admiral Roger Keyes, is a German submarine pen.

The raid led by HMS Vindictive loses all hope of surprise when the wind direction changes and a smokescreen intended to conceal the attack is blown offshore, leaving a large landing party of marines and sailors exposed to intense enemy fire from batteries on a breakwater “mole” in the harbour and from the shore.

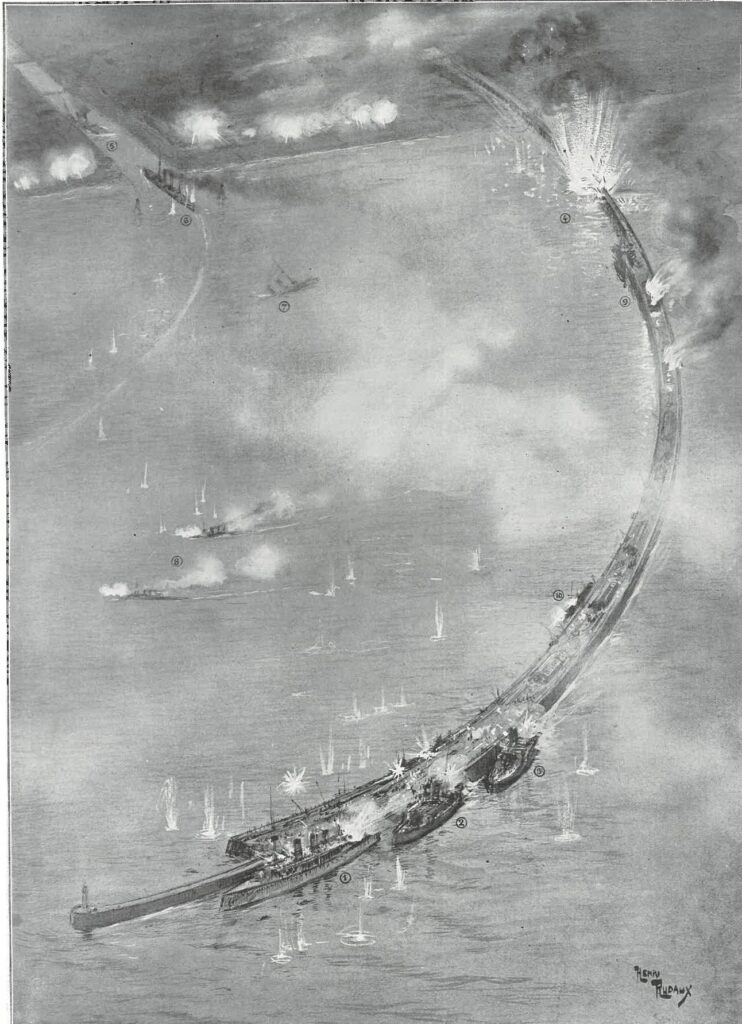

Drawing depicting the raid on Zeebrugge

Three old ships, filled with concrete, are scuttled in a bit to obstruct the U-boats. One grounds in the wrong place but a drawing in L’Album de la Guerre suggests the other two achieve their mission by blocking a canal leading to the submarine base.

What is not reported is that, within days, the Germans dredge around the vessels, restoring their unimpeded access to the English Channel and North Sea. Ostend is attacked at the same time, without success. The Royal Navy loses nearly 600 dead and wounded. A second raid on Ostend on May 9, 1918, is hampered by sea fog.

The raids are trumpeted as victories. Eight Victoria Crosses are awarded for Zeebrugge and three for the later attack on Ostend. Keyes receives a knighthood.

During the war, Germany’s U-boats sink 30 Royal Navy ships and nearly 6,000 merchant and shipping vessels, with enormous loss of life. The sinking of the Lusitania, torpedoed off the southern coast of Ireland on May 7, 1915, claims the lives of 1,198 passengers and crew alone. Germany justifies the attack because the liner is carrying munitions.

Victory and thanksgiving

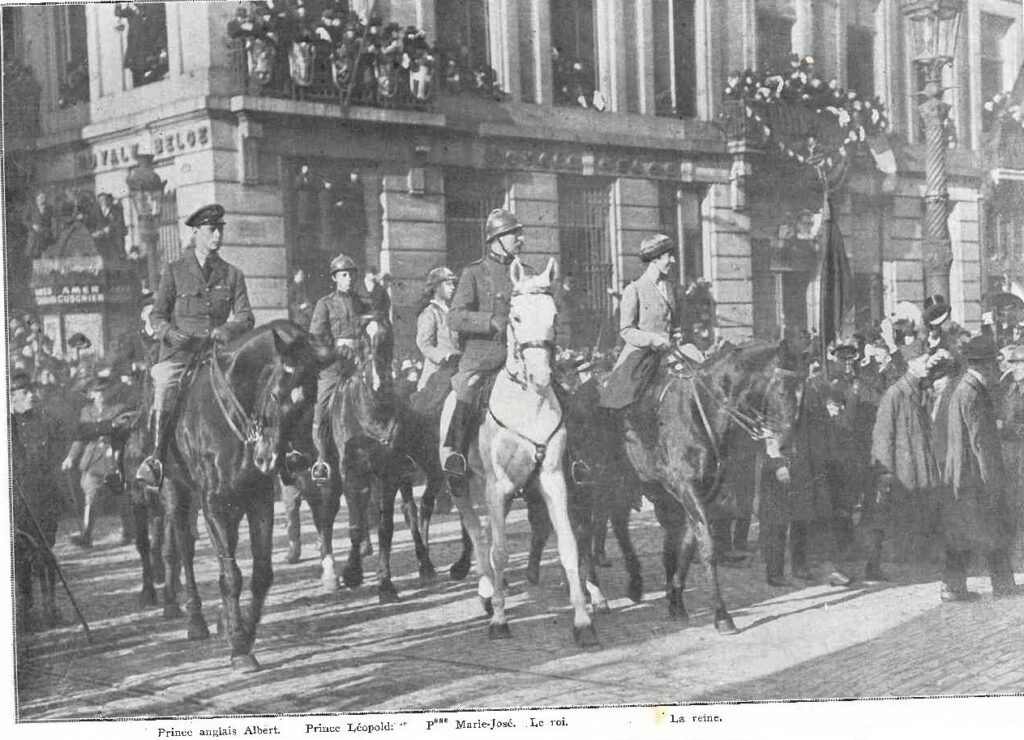

The Armistice is marked by an outpouring of emotion in Belgium. On November 22, 1918, Queen Elisabeth and King Albert, helmeted and in full uniform, enter Brussels on horseback, with their children, Leopold, 17, Charles, 15, and Marie-José, 12, as well as Britain’s future King George VI. They arrive at the Parliament amid joyous scenes “with the crowd waving hats, hands and handkerchiefs” to celebrate a victory which comes at a high cost: 50,000 Belgian military and civilians have lost their lives.

The victory celebrations continue for months. The album reports on a speech by French President Raymond Poincaré at the Belgian Chamber of Representatives on July 22, 1919. “When two peoples have completed this sublime mission side by side, nothing, nothing, nothing can ever separate them,” he declares to rousing cheers. Afterwards, he is greeted by a huge crowd in the Grand Place singing La Marseillaise and La Brabançonne.

French President Raymond Poincaré with the royal family and Marshal Foch at Brussels' Grand Place

The following day, the King and Poincaré take part in a thanksgiving service at St. Rumbold’s Cathedral in Mechelen. Poincaré decorates courageous Cardinal Désiré-Joseph Mercier, famed for speaking out against the occupiers and his defiant letter, Patriotisme et Endurance. Poincaré also visits Liege, where he presents the entire city with the Légion d’honneur.

Albert I, the great-grandfather of Belgium’s present King Philippe, dies in a climbing accident at Marche-les-Dames on February 17, 1934. Elisabeth lives to see her grandson Baudouin become King. She dies in Brussels, aged 89, on 23 November 1965.

Kaiser flees

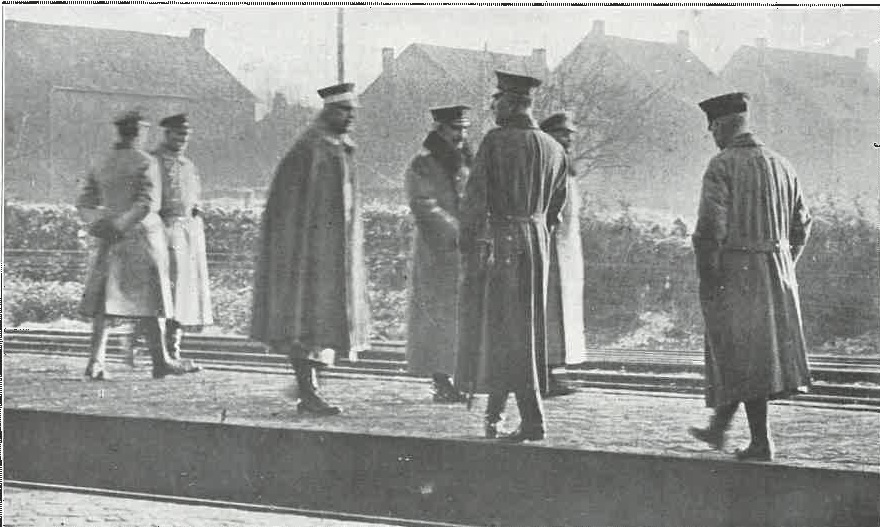

German Kaiser Wilhelm II flees into exile on the eve of the Armistice, quitting his Belgian headquarters in Spa and crossing the frontier by car into the neutral Netherlands. L’Album de la Guerre shows the dejected Emperor waiting for a train on the station platform at Eijsden. George V describes his cousin as “the greatest criminal in history” but rejects Prime Minister David Lloyd George’s demands to hang the Kaiser. The Dutch, in any case, refuse to extradite him.

Kaiser at Eijsden station after fleeing to the Netherlands

Given refuge by Count Godard Bentinck at Kasteel Amerongen, Wilhelm formally renounces the Prussian and imperial thrones on November 28, 1918. He buys Huis Doorn from Baroness Wilhelmina Van Heemstra, the grandmother of Brussels-born actress Audrey Hepburn, in May 1920. He grows a beard and lives there peacefully, with his two wives (after Augusta, mother of his seven children, passes away in 1921 he weds Princess Hermine of Greiz), until his death on June 4, 1941. His great-great-grandson Prince Georg von Preussen recently filed legal claims for the restitution of property that belonged to the Kaiser.

L’Illustration

After the Armistice, L’Illustration receives many requests from veterans and families for reprints of editions from the conflict. Editor René Baschet spots an opportunity and, in 1922, brings out the first edition of L’Album de la Guerre, a compilation of the newspaper’s wartime coverage, augmented with new content, in two super-sized, cloth-bound volumes.

The album opens with a series of handwritten messages, praising Baschet’s initiative, from six moustached Marshals: Joseph Joffe, Ferdinand Foch, Émile Fayolle, Louis Franchet-d’Espèrey, Hubert Lyautey and Philippe Pétain. After his country’s surrender in the Second World War, “Lion of Verdun” Pétain becomes head of the Vichy France puppet government. Convicted of treason, he is saved from the firing squad by the intervention of one of his former junior officers, Charles de Gaulle.

Arrival of Belgian King and Queen at Parliament after Armistice

Totalling 1,340 pages and featuring more than 2,500 mostly black-and-white photographs, as well as striking colour images, L’Album de la Guerre is an instant hit. The first two print runs of 30,000 copies quickly sell out and L’Illustration produces a third edition in 1923, followed by nine more – 200,000 copies in all – during the inter-war period.

The Fall of France in 1940 and occupation puts paid to further distribution. It’s easy to see why: the triumphalist tone of the reporting and unsparing images of German dead, captured Germans and executions of Boche collaborators do not sit well with the new regime. The authorities impose a new “political editor” at L’Illustration, Jacques de Lesdain. The newspaper supports Pétain and appears until it is banned in September 1944 by the restored French government. Its offices and printworks are seized by the state.

De Lesdain flees and helps set up a short-lived collaborationist radio station in Sigmaringen, Germany. Condemned to death in absentia, he makes his way to Italy, gains political asylum and works in Rome for the French Embassy and Vatican newspaper L’Osservatore Romano, under the protection of German Cardinal Josef Frings. There is no trace of him after 1976. Baschet is cleared of personal wrongdoing, but his business is forced to close for good in 1949. He dies the same year.