English is more suitable than ever as the lingua franca of the European Union, but it must be resolutely dissociated from Shakespeare and from the British flag.

Philosopher Philippe Van Parijs reflects on current events and debates in Brussels, Belgium and Europe

Brexit made English shrink to one of the minor native languages in the European Union. Judging by the most recent Eurobarometer language data, it must now be competing with Danish and Russian for the 14th position. Does this mean that it will lose its dominant position within and around the European institutions? Of course not.

As co-official language in Ireland and Malta, English managed to be retained as one of the EU’s official languages. It is taught as a foreign language to over 97% of the EU’s pupils, far more than any other language. And most crucially: when Europeans who do not have the same native language meet, English is in most cases the maxi-min language, in other words, the language best known by the conversation partner who speaks it least well.

This means that the use of English makes communication less laborious and that it excludes less people than if any other language were used. The systematic spontaneous use of the maxi-min language creates countless opportunities to practice it and keeps feeding the motivation to learn it and to get one’s children to learn it.

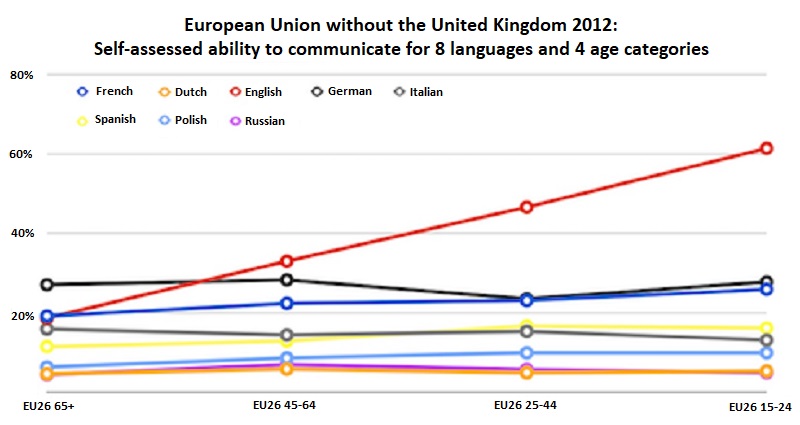

This is the bottom-up process that has propelled English far above all other languages among young Europeans and that will keep doing so.

Data base: Eurobarometer Special Languages 2012. Data processing: Jonathan Van Parys

Is it not however problematic to retain English as the EU’s lingua franca, since the United Kingdom left? On the contrary. English is no longer the native language of the bulk of the population of one of the EU’s biggest member states. Nor is it any longer the language of national identification in any of the EU’s 27 member states. For the Irish and the Maltese, English is just the remnant of a colonized past.

Consequently, Brexit has made English a more neutral language. It has thereby become more suitable than ever as the EU’s lingua franca.

Any attempt by one of the remaining larger member states to impose its own national language on the EU is doomed to meet fierce and decisive resistance. It would amount to trying to recreate an injustice the removal of which was one of the few benefits Brexit brought us.

However, it is important that our attitude towards English should change. English is a continental language. Its Germanic component was imposed on the British population by the Angles in the 5th century AD and its Romance component by the Normans in the 11th.

The result is a mixture of German (or Dutch) and French, which we must serenely reclaim as our common second language. Obviously not as a substitute for our many national languages nor as a core element of our identity, but as an essential instrument for communicating among ourselves, with the wide variety of our accents.

As the then German president Joachim Gauck put it in 2013, “the ability to speak enough English to get by in all in situations and at all ages” is a condition for the realization of his “wish for Europe’s future: a European agora, a common forum for discussion to enable us to live together in a democratic order”.

Giving English this role requires that we stop viewing it and referring to it as “la langue de Shakespeare”. The English we must master is not the literary idiom required to enjoy a performance in Stratford-upon-Avon.

It is the English the Portuguese and the Slovaks need to know in order to discuss the price of sardines and the future of the world. More importantly, we must stop associating English with the British flag, as we too often do.

For example, when connecting to wifi on Eurostar, you are invited to click on the flag of France if you want to access the website in French and that of Belgium if you want to access it in Dutch.

Both are offensive enough for a Francophone Belgian. But what is even more lamentable is that you are invited to click on the flag of the United Kingdom if you want to access the website in English.

One can understand the temptation: out of the twenty-seven member states of the EU, twenty-four have adopted the name of their language as the name of their country. But the Union Jack is not the flag of England. And above all, using the ISO abbreviations (FR, NL, EN, etc.), as the European institutions do systematically, would serve the purpose just as effectively, while being less imbued with the nationalistic appropriation of languages and more respectful of what English has now become for us Europeans.

Eurostar is just one example. Many other public and private websites do the same. It is high time to take action.

Related News

- Why did Brussels become the capital of Europe? Because Belgium starts with letter B!

- Europeans and their languages: Is multilingualism dying in the EU?

- Embrace 'bad English' as the European 'lingua franca,' says Timmermans

- Dutch retailer Action posts €11.2bn in nine-month sales as expansion across Europe accelerates

- Europe’s language revolution, now more visible than ever