In a little-known region of Belgium, located on the borders of Germany and the Netherlands at the edge of the Liège province, the names of its communes, such as La Calamine and Plombières, give away the secrets of its mining and industrial past. In the 19th century, Calamine and Plombières were, in fact, the epicentre of zinc and lead production in the world.

These days, there is almost no trace of this industrial past left in the region. Nature has reclaimed many of the former industrial regions. The mines are now plugged, and a thick layer of vegetation covers the landscapes. Yet the subsoil is still home to mineral treasures.

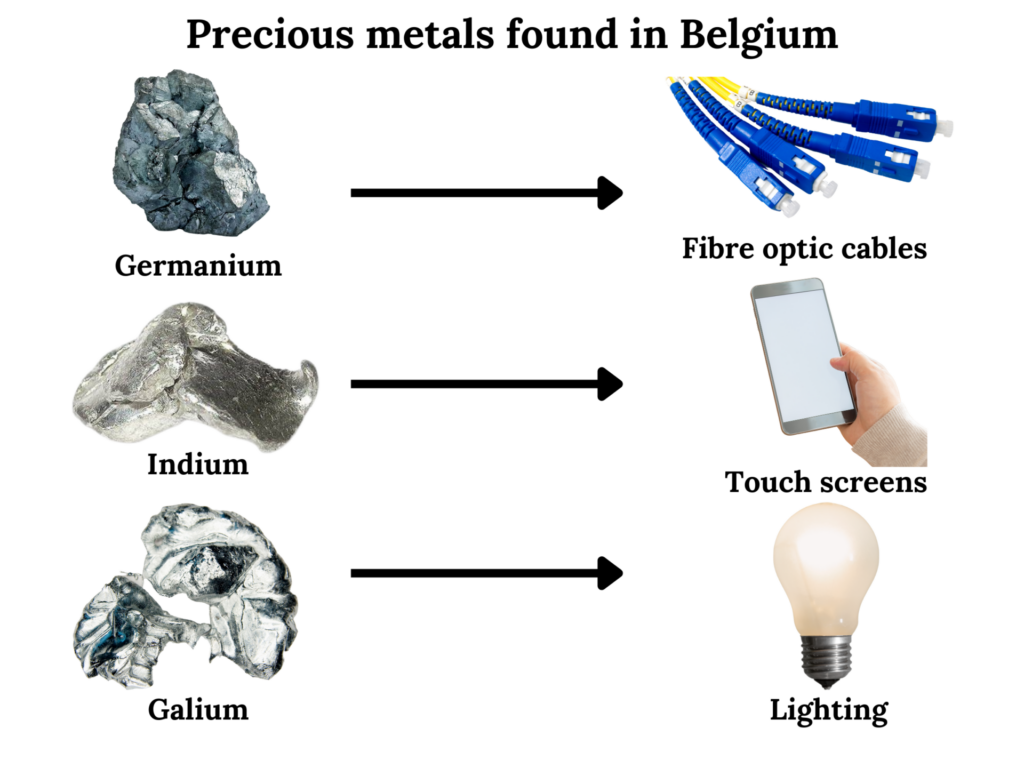

"With the mineralisation of lead, and zinc, we find a procession of other elements, such as germanium, gallium and indium,” says Eric Pirard. a professor from the University of Liège and a specialist in geo-resources.

These precious metals are, in particular, prized in the development of new technologies. Germanium is very valuable for the manufacture of optical fibres, indium for touch screens and gallium for lighting and optoelectronic sensors.

Graphic made by Abby Stetina for The Brussels Times

The idea of once more harnessing the treasures below the surface has been explored as recently as 2018 but the exploration project put forward by the private company Walzinc was rejected by the Walloon Region.

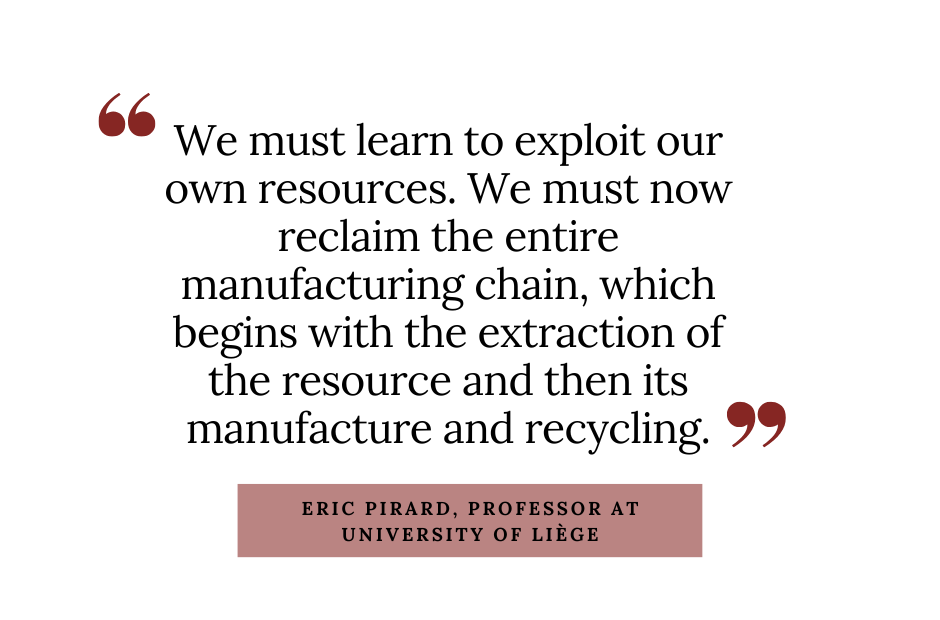

Pirard believes, however, that the return to mining production should be seriously considered.

"We cannot live by outsourcing all the impact of industrial activity,” he says. “It's too easy to have Chinese workers make the products that make our daily lives more comfortable. We must learn to exploit our own resources. We must now reclaim the entire manufacturing chain, which begins with the extraction of the resource and then its manufacture and recycling."

Pirard explains that past concerns around the safety of mining are outdated in this day and age as discharges and pollution are controlled and mining galleries are excavated by robots.

Most of the inhabitants of the region are not against a return to mining but not everyone, including Marie Stassen, the mayor of Plombières, is convinced.

"It has been more than 100 years since the mines closed down in our region,” she says. “We have developed a completely different type of economy based on agriculture and tourism. Tourism is, moreover, our third largest provider of employment in the region. The opening of new mines would have a fundamental impact on this economy, without counting on the water in our subsoil. Our water is exported to the Netherlands. It's our gold in this region."

Related News

- Antwerp uses blockchain to support artisanal diamond mining in DR Congo

- Confidence in the Belgian economy still low among business leaders

- ECB President sees gloomy economic outlook for Eurozone

The issue is a sensitive one in Belgium but other areas around Europe where deposits could be found may be less concerned. Lithium, the metal essential to the manufacture of batteries, could be extracted in Europe more systematically to reduce our dependence on China. Lithium is increasingly used to store energy produced by solar panels and wind turbines and in electric cars.

According to the World Bank, graphite, lithium and cobalt production is expected to increase by nearly 500% by 2050 to meet climate targets. European officials estimate that to reach its targets, the European Union will need 18 times more lithium by 2030 and nearly 60 times more by 2050.

Yet Europe has only one lithium mine, in Portugal. The vast majority of its needs are currently covered by non-European imports. About 87% of unrefined lithium in the EU comes from Australia. However, more than half of the extracted metal is processed in China.

In fact, more than 70% of lithium-ion batteries are produced in China. The EU is aware of this dependence. It has therefore added lithium to its list of critical raw materials.

However, Europe does not lack potential. Lithium is present in salt lakes in the form of brine, or rock. Therefore, there could be significant deposits of lithium in Europe: in Portugal, Spain, Serbia, Great Britain, Finland and Germany.

"These are two very different types of exploitation,” says Pirard. “With regard to the exploitation of brine, many believe that it uses a lot of water. In reality, brine is water heavily loaded with salt. It is simply evaporated to recover lithium. Therefore, we do not consume water. On the contrary, water is purified."

According to Pirard, there would therefore be no major pollution problems related to the exploitation of lithium unlike, for example, the exploitation of copper.