In 2009, the Brussels regional parliament sent a birthday greeting to itself to mark the 20th anniversary of the creation of the Brussels Capital Region.

It celebrated the moment in 1989 when Brusseleirs “took their destiny in hand, especially urban planning”, wresting these decisions from a national government of “Walloon and Flemish ministers with little regard for the environment and quality of life in the capital, where most of them came only for work.” Planning was to be “the keystone” of policymaking, it added, recalling the 1960s and 70s, when “citizen movements had denounced the ‘Brusselization’ of the Belgian capital, an expression that rapidly took hold in Belgium and abroad.”

All this begs the question: what do people mean when they talk about bruxellization/verbrusseling or Brusselization?

It is widely thought to mean damaging, top-down, urban planning policies imposed by those who do not live in the city, inducing a gloomy sensation of helplessness in those who do. And a post-war phenomenon that could be halted by placing decision-making closer to the people who must live with its consequences.

But that assumes Brusselization started in the 1950s and is still happening, 33 years after the Brussels region took responsibility for planning. A recent decision by Belgium’s Council of State to halt demolitions for a vast development scheme in the emblematic 19th century Place de Brouckère at the heart of Brussels suggests otherwise.

Geoffroy Coomans de Brachène, councillor of the city of Brussels from 2012 to 2018 and active in the heritage movement, offered his take on Brusselization in a recent television interview. As a former alderman for Urbanism and Heritage, he must have thought about it a lot. Perhaps reflecting the absence of any formal definition of the term (it’s not in my dictionaries), he lifted his words from Wikipedia: “It is the term used by urbanists to refer to the upheavals of a city surrendered to developers to the detriment of the quality of life of its inhabitants under the guise of necessary modernisation.”

It is not clear why this process, which affected most large cities to some degree across western Europe, came to be so associated with Brussels to the point of co-opting its name. Whatever the reasoning, it has, perhaps unfairly, come to shape the image of Brussels both internally and externally as, well, a bit of a mess.

Brussels-as-Bruges

In its introduction to the city, the 2016 Lonely Planet guide to Belgium and Luxembourg refers to the “architectural vandalism that’s now widely known as Brusselisation.” In its introduction to Bruges meanwhile, the guide promises a city where, “picturesque, cobbled lanes and dreamy canals link photogenic market squares.”

Yet until the 1870s, central Brussels resembled Bruges more than a little, as we can still see from photographs and paintings of the time.

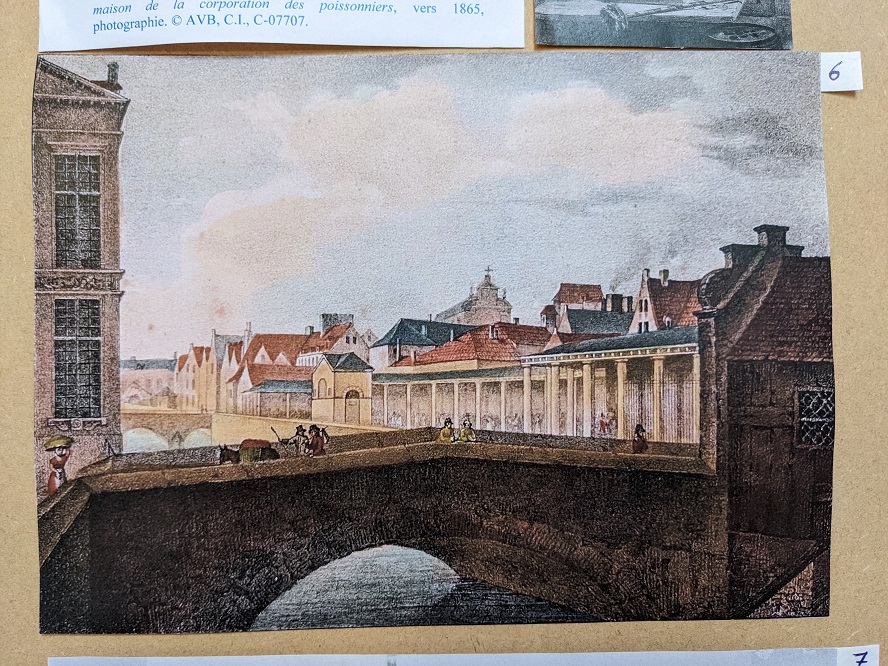

The Bridge of the Fishmongers and the Fish market, 1825 by Jean-Louis Van Hemelryck. Coloured lithographie in 1865 by Marcellin Jobard.

Most of those images were taken to record the passing of Brussels-as-Bruges, ahead of a vast development scheme to transform the provincial court city on the fringe of a vanished empire into the modern capital of a young nation worthy of comparison with its peers.

The river Senne by Brussels' Fish market

What appears picturesque to 21st century eyes looked broken and obsolete in the mid-19th century. While the canals of sleepy Bruges dreamed on, the various branches of the Senne river in bustling Brussels were regarded as flood-prone incubators of disease.

The decision to cover the entirety of the river in central Brussels was the most radical of the 25 elements in a vast infrastructure plan announced by mayor Jules Anspach in 1863. This included new water and sewage installations and a host of public buildings to provide modern urban services.

In clear imitation of Baron Haussmann’s Paris, transforming since 1852, wide boulevards bisected the city, built partly over the river and erasing much of the picturesque charm of lower-town Brussels through which it had always meandered. The new central boulevards were to be lined with Paris-style apartment blocks.

Place de Brouckère in the Belle Epoque era

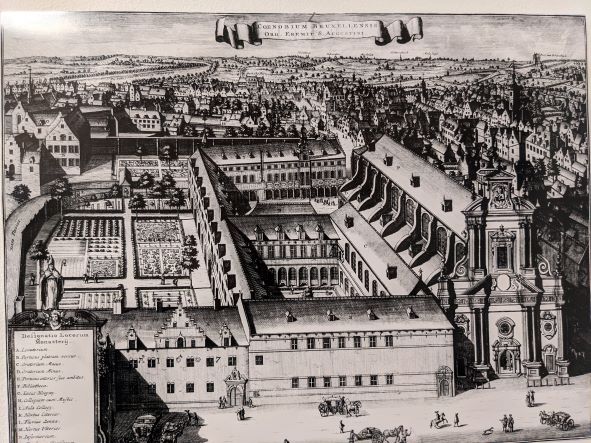

Three-quarters of its way north, the boulevard split to form a y-shape, passing each side of the Temple des Augustins, a 17th century convent church. The Senne, which had once flowed alongside the convent’s beautiful gardens, gave way to the western side of present-day Place de Brouckère. The church, a “shapeless slum”’ according to Anspach, stood on the square for two decades before being demolished to ease traffic and allow visitors an unfettered view of the new square (the façade of the church was re-used for the Church of the Holy Trinity in Ixelles).

Temple des Augustins and the Senne river, now Place de Brouckère.

Commercially, the boulevards were successful for several decades, packed with eateries, cafés, shops and attractions (as the directories of the time show), in line with the plan to remake the centre as an entertainment and consumption zone. This was the world where, in the words of his song Bruxelles, Jacques Brel’s grandparents paraded in open-top buses, resplendent in crinoline and top hat.

The city also impressed foreign visitors of the time and, briefly at least, met the pretensions of joining the top tier of modern cities. “Brussels has many points of resemblance with the French capital and is not unfitly termed a ‘Paris in miniature’,” Baedeker reported in its 1881 Guide to Belgium and Holland.

Paris on the cheap

With the river paved over, Brussels-as-Bruges was erased forever. A disappointment perhaps for visitors now, but in the same edition of Baedeker, the editor describes the “melancholy, deserted appearance” of Bruges, pauper-ridden and “its commerce quite insignificant,” where retired merchants spent “the evening of a busy life”. The guide also welcomed the “the pleasing variety of the handsome buildings” flanking the new Brussels boulevards, thanks notably to prizes offered by the public authorities for the finest facades.

However, while prosperous locals flocked to the new department stores, theatres and cafés of the revamped Brussels, they did not want to live there. Homeownership was increasingly central to the urban bourgeoisie, and a law allowing freehold apartments was decades away.

Although superficially impressive, expropriation costs had limited the footprint of the new boulevards. Where their Parisian counterparts were arranged around generous courtyards, the noble stone facades of the central Brussels boulevards concealed cramped, dingy flats. The rooms at the back overlooked tiny air shafts or crumbling older houses spared demolition in the interests of economy.

An English firm, the Belgian Public Works Company, was chosen to oversee the transformation project for the boulevards (without a competitive tender), including the residential developments. After an embezzlement scandal, the company was dissolved in 1871 and the management (and liabilities) for the scheme, were left in the hands of the City of Brussels. It appointed a Parisian contractor to complete the apartments as quickly as possible.

West side of Boulevard Anspach looking north towards Place de Brouckère. Credit: Frédéric Moreau

1879, Baron Anspach was dead, the Parisian entrepreneur was bankrupt, and of 62 Haussmann-style buildings erected along the central boulevards, only seven found private buyers. The city was obliged to acquire the rest, as well as bailing out much of the rest of the transformation scheme. To this day, the City of Brussels still owns many of these buildings and struggles with finding a purpose for them.

But does this make the 1860s boulevard scheme, with its centrepiece at Place de Brouckère a destructive failure, the patient zero of Brusselization?

Tunnels to nowhere

We have been schooled to value older architecture to a degree that would have been incomprehensible to Anspach. The central boulevards have long since entered that category, with appreciation only growing since much of the area was pedestrianised in 2015. Should these schemes not be judged also on their good intentions and their potential?

The creation of the central boulevards rotated the historical east-west access of Brussels through 90 degrees. Brussels had gone from being a provincial court along the route between Flanders and the crazy-paving of the Holy Roman Empire to a national capital in a north-south axis between Amsterdam and Paris.

Over the century following the city centre shake-up, further vast upheavals altered the face of Brussels to improve its communications. However, a tunnel between the north and south train stations, proposed as part of Anspach’s downtown improvements in the 1860s, was rejected: King Léopold II, Anspach’s sponsor, wanted a station closer to the Royal Palace. Eventually, a 1903 law authorised a route further east on the slopes below the park, where the city’s finest medieval families had built their steens, or stone mansions.

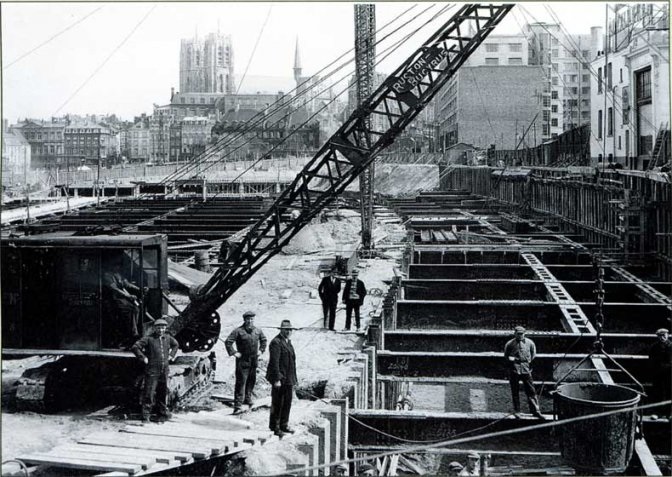

Demolition work began in 1911. It stopped at the outbreak of the First World War and only resumed in 1935. Other perennial obsessions of the planners – a grand link between the lower and upper towns, a national library, a cité administrative placing the state’s 14,000 civil servants at a single site – took seed along the route of devastation.

Demolitions during construction of the north-south tunnel junction

When the North-South rail link (Jonction Nord-Midi or Noord-Zuidverbinding) finally entered service in 1952, it delivered a royal waiting room in the Central Station but left the entire eastern flank of the Pentagon uninhabitable (at least for those with any choice in the matter).

Tunnels construction at Place Stéphanie in 1956, from archives Ministère des Travaux

Work soon began on a system of road tunnels aimed at wowing visitors to Expo 58. These devastated Avenue Louise and the once-admired tree-lined boulevards bordering the city centre. Those still living in the grand, 19th century houses departed Brussels. Their homes were demolished and replaced by office blocks employing commuters also living and paying their taxes elsewhere.

Manhattan Project

A decade after Expo 58, wrecking crews moved into the working-class northern quarter of Brussels for the so-called Manhattan Project, a vast modern business district modelled on American skyscraper cities. This scheme was cherished by urbanists for decades and finally activated by Paul Vanden Boeynants, a city alderman and national politician known by his initials VdB, and property developer Charly De Pauw.

Promising a new era of prosperity for Brussels, it swept away more than 700 buildings and at least 12,000 people lost their homes. Again, demolitions raced ahead of the budget to rebuild: the 1970s oil shock halted work and another swathe of the city lay blighted and without citizens.

At a time when the city was again emptying itself of inhabitants, the developers of the Manhattan Project also secured a permit for a vast, x-shaped modernist tower from which the city could administer its dwindling numbers. It was joined by the h-shaped Philips Tower, of similar dimensions and style. A century after Anspach’s transformations altered the lower town forever, the two new towers stood at the head of the boulevard bearing his name and dwarfing the buildings at its heart on Place de Brouckère. Over the following 30 years, the population of Brussels’s historic centre would fall by almost 30%.

Place de Brouckère during the pedestrianisation work in 2018 with the Philips tower in the background. Credit: Belga

All these schemes brought incalculable environmental damage and scared taxpayers and tourists away from the city. Their failure or at least obsolescence left these would-be assets as liabilities in public hands, bequeathing a legacy of choosing between ruinously expensive demolition or ruinously expensive maintenance (renovation of the tunnels alone has been priced at over half a billion euros). But what of Brusselization in the new, citizen-focused era? Has the Brussels Capital Region put an end to the carnage since its creation in 1989?

Tipping point

In April 2022, the Conseil d’État, Belgium’s highest administrative court, suspended the permit for a radical, €88m development project at Place de Brouckère. An entire city block on its western side was to be demolished, save the (legally protected) cinema and the facades of a row of houses dating from the square’s creation. The proposed Brouck’R project, including a hotel, apartments, student housing, offices and car park, would fill this space, topped by a bronze-coloured box rising 11 metres above the ornate roofline of the 1870s houses. The court said the region had failed to address objections from its own heritage experts.

The Royal Commission for Monuments and Sites (CRMS in French, KCML in Flemish), a panel of specialists in the built environment, must be consulted when a development affects buildings deemed to have heritage value. In ascending heritage importance, such buildings can be listed on the region’s online inventory, on a much smaller register of protected sites and buildings or among those classed as monuments. The CRMS/KCML issued a “firmly unfavourable” opinion on the Brouck’R project.

Since a recent change in the rules, the CRMS opinion is no longer binding on non-protected buildings, and a civil servant appointed by the Brussels Capital region (the fonctionnaire délégué) makes the final decision on whether to issue a permit after the individual council has examined the application.

For the Brouck’R project, the City of Brussels’ planning committee decided that the developer’s offer to paint the rooftop metal box champagne colour, instead of bronze in the original plan, “offers a better appreciation of the historic facades”. The CRMS was not convinced and reiterated its negative advice, adding that it “deplores” the scheme. Nevertheless, such reassurances carried the day with the region, and its official issued the permit for the project in July 2021 (the summer holiday period being popular for making potentially unpopular decisions).

Inter-Environnement Bruxelles, a federation of 80 citizen pressure groups from across the Brussels region, appealed the decision to the Conseil d’État, and the court suspended the permit, leaving the roof extension hanging. It said the regional authority’s decision to grant a permit for such a scheme was “a patent error of assessment… [and] incomprehensible to any informed observer.” The presence of the threatened buildings on the online heritage inventory showed that the region had failed to address the objections of the CRMS concerning the quality of the buildings, it added.

Such a decision could have far-reaching consequences for developments targeting any buildings included in the inventory (structures built before 1932 are automatically included, on a provisional basis at least).

What price the sublime?

In 2017, the City of Brussels hosted an exhibition in the grand, Anspach-era Bourse (stock exchange), called ‘Sublime Bruxelles’. This celebrated Anspach’s creation of the central boulevards, “the buildings and their remarkable architectural details… centred around place de Brouckère.” It concentrated on those that won the prizes for best facades. Among these were buildings on the square about to be filleted and topped with a metal cage in the teeth of opposition from citizen movements and the CRMS, whose mission is to “preserve heritage in order to invent the future”. So, what of the promises of the past, to end Brusselization by placing decision-making closer to the city’s inhabitants? Were they just a façade too?

Facadism. Why not just call it demolition?

Since the creation of the Brussels-Capital Region in 1989, developments erasing vast parts of the city have given way to approaches that acknowledge, at least partly, heritage value. Most notable among these is facadism, the practice of retaining certain elements (often the listed elements) of a building's street frontage while demolishing much or all of the interior.

Facadism creates a reductionist view of architecture as little more than two-dimensional elevations, as if returning buildings back to the drawing board. At the same time, this approach has generally seen exterior masonry prized over other original features such as doors, window frames, glass (stained or not) and ironwork.

Facadism in Brussels almost invariably alters the building's roofline and scale altering its impact and relationship with its immediate environment. Its detractors argue that it is the negation of the concept, a distinctively Brussels concept, of the building as an art total (design, materials, fittings, scale and silhouette as a complete package). Its defenders, especially developers and planners, argue that facadism retains the essence of a building and prolongs its existence by adapting it to new social and economic realities (extra space, car parking, security, lower maintenance costs).

Hotel Astoria facadism in 2022. Credit: Frédéric Moreau

An example of facadism in action can be seen in Brussels in the former Hôtel Astoria at Rue Royale 103. The developers removed every element not legally protected to create a modern international tourist experience. Built in 1909 to attract tourists to the Brussels International Exposition of 1910, the Astoria originally evoked New York luxury-living of its period. It was a restrained but recognisable nod to turn-of-the-century Fifth Avenue's muscular foursquare digest of Paris and Loire Valley taste reimported into Europe. However, while the new hotel’s plans incorporate certain grand elements of the interior, it is no longer a Belle Époque building: its street presence is now reduced to a flat plane framed within a crown of self-effacing 2020s architecture.

Where to see facadism in Brussels:

· Boulevard Bischoffsheim 29-35. The facade of a neo-Louis XVI style mansion is spectacularly engulfed in an office development of 1989.

· Avenue des Arts 10-11. The facade of the 1840s neoclassical home of architect Jean-Pierre Cluysenaar (also designer of the Galeries Royales Saint-Hubert) was classed as a monument in 1992. In 1993, it was topped with a nine-storey block which gives a tiresome postmodernist wink in the style of the building it is crushing. The entrance hall and two salons were retained inside.

· Rue Duquesnoy 14. The former Marché de la Madeleine, also by Jean-Pierre Cluysenaar. While the neo-Italian renaissance facade survives, its interior was destroyed in 1957 and replaced by the City of Brussels' festival hall. The market, one of the first large metal constructions in the city, was itself created as part of a vast 1840s facadism project on a late baroque mansion round the corner at Rue de la Madeleine 55. The mansion itself had already been repurposed as an international stagecoach terminus (Cluysenaar's 1840s Galerie Bortier survives behind the facade and is well worth a visit).

· Place du Luxembourg. The classical stone facade of the former Brussels-Luxembourg station from 1854 was listed as a monument in 1991. The building it masks houses the Station Europe information centre for the European Parliament.

· Rue Montagne aux Herbes Potagères 2. The former Foire de Leipzig department store from 1864 by Antoine Trappeniers. The facade was converted for a bank in 1906 by Paul Saintenoy and is the only element remaining after a 1985 conversion. You may know it as the entrance to Scott's Bar & Kitchen.

· Place de Brouckère, west side. Numbers 8-28 of the square were built in a busy, commercial style in the 1870s, with richly sculpted stone details evoking the nearby Grand Place. The regional inventory describes them as eclectic with neo-gothic tendencies. They have hosted an ever-changing cast of shops and restaurants at street and mezzanine level and businesses above. Several were left empty and blighted (number 14 went from a dairy in 1880 to a German wine bar in 1914, ending its life as Pizza Hut a few years ago, when it was shuttered, with and its windows greyed out). If the Brouck’R development goes ahead, the seven facades will form the outer skin of a hotel, their rooflines blurred by tall new volumes above them.