More than two weeks since a NASA satellite collided with an asteroid, data shows that it did successfully change the asteroid’s orbit – the first time this has ever been done.

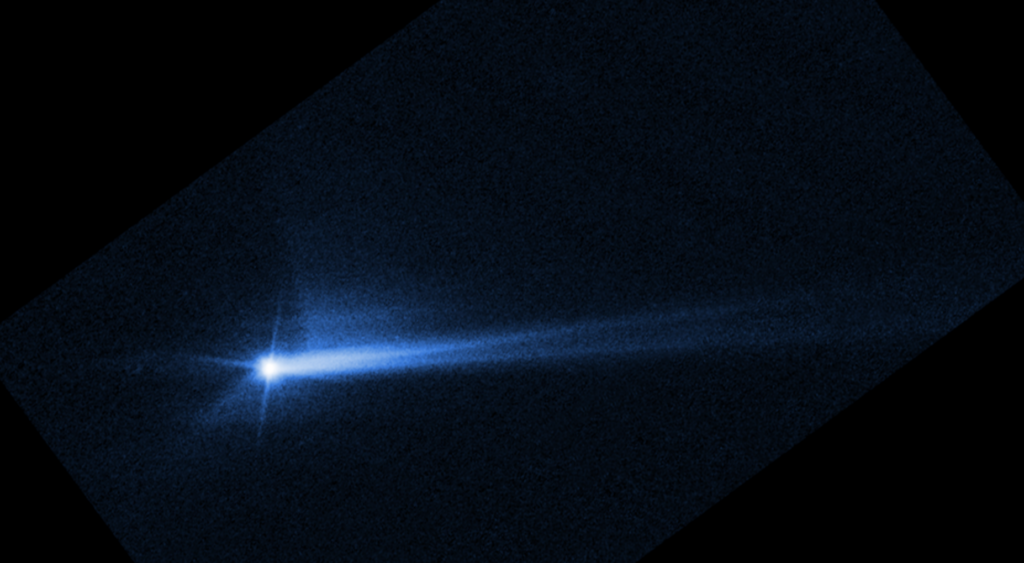

At the end of September, NASA announced the intentional collision between its Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) and the asteroid target Dimorphos, which was the size of five football fields, was successful. The multi-million dollar craft slammed into the huge space rock at 24,000 km/h.

Analysis of data obtained over the past two weeks has now shown the spacecraft's kinetic impact – the technique of intentionally colliding with an object to divert its course – with DART successfully altering the asteroid’s orbit.

The asteroid didn't pose a threat to Earth as the collision occurred about 11 million kilometres from our planet. But the mission showed that if a large asteroid was hurtling toward our planet, it would be possible to divert its course using this technique.

“All of us have a responsibility to protect our home planet. After all, it’s the only one we have,” said NASA Administrator Bill Nelson when announcing the results.

“This mission shows that NASA is trying to be ready for whatever the universe throws at us and is a watershed moment for planetary defence and all of humanity."

Continued analysis

Since the intentional collision, astronomers have been using telescopes on Earth to measure how long it took for Dimorphos to complete a full orbit of its larger parent asteroid, Didymos (before the mission, this was almost 12 hours).

Related News

- NASA spacecraft crashes into asteroid in successful planetary defence mission

- A Soyuz rocket takes off for the ISS with an American and two Russians on board

The investigation team now confirmed that this course has been altered by 32 minutes, shortening the 11 hour and 55-minute orbit to 11 hours and 23 minutes. Despite these already positive results, more data will be collected to study the longer-term impact. Over time, the change in course is amplified as the Diomorphus moves further and further from its original course, meaning that an initially small change in direction can have considerable effects.

“As new data come in, astronomers will be able to better assess how a mission like DART could be used in the future to help protect Earth from a collision with an asteroid if we ever discover one headed our way," Lori Glaze, director of NASA’s Planetary Science Division, said.