In a major break with its formerly rigid budgetary strictures, the EU Commission has proposed a flexible scheme for countries to reduce their debt and budgetary deficits to comply with EU fiscal rules.

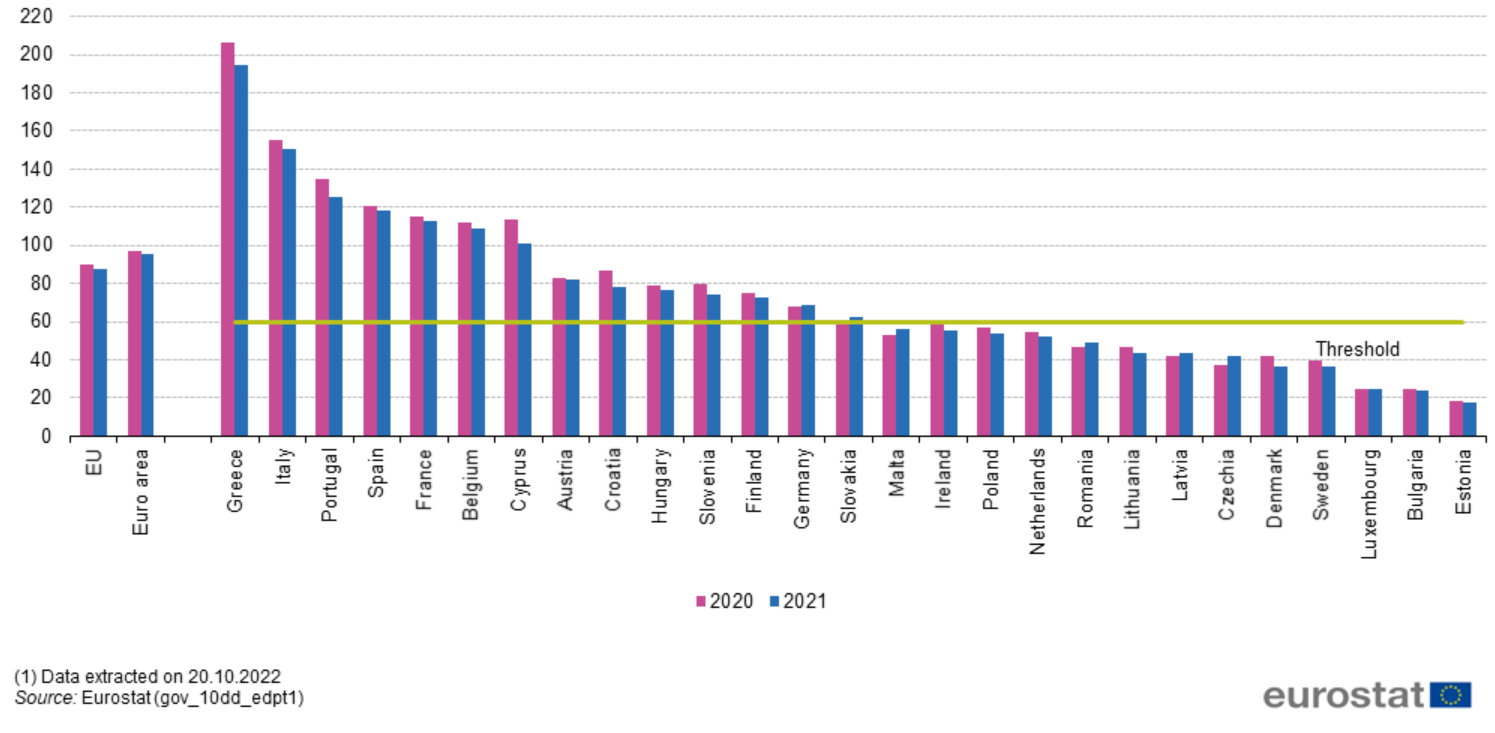

Under the bloc’s current ‘one-size-fits-all’ policy, countries whose debt-to-GDP ratios exceed the EU’s legal threshold of 60% are obliged to reduce the amount of debt above this limit by 1/20th each year.

Under the new scheme, however, Member States whose debts exceed this ceiling will be able to pursue a more tailored, country-specific plan to achieve fiscal compliance.

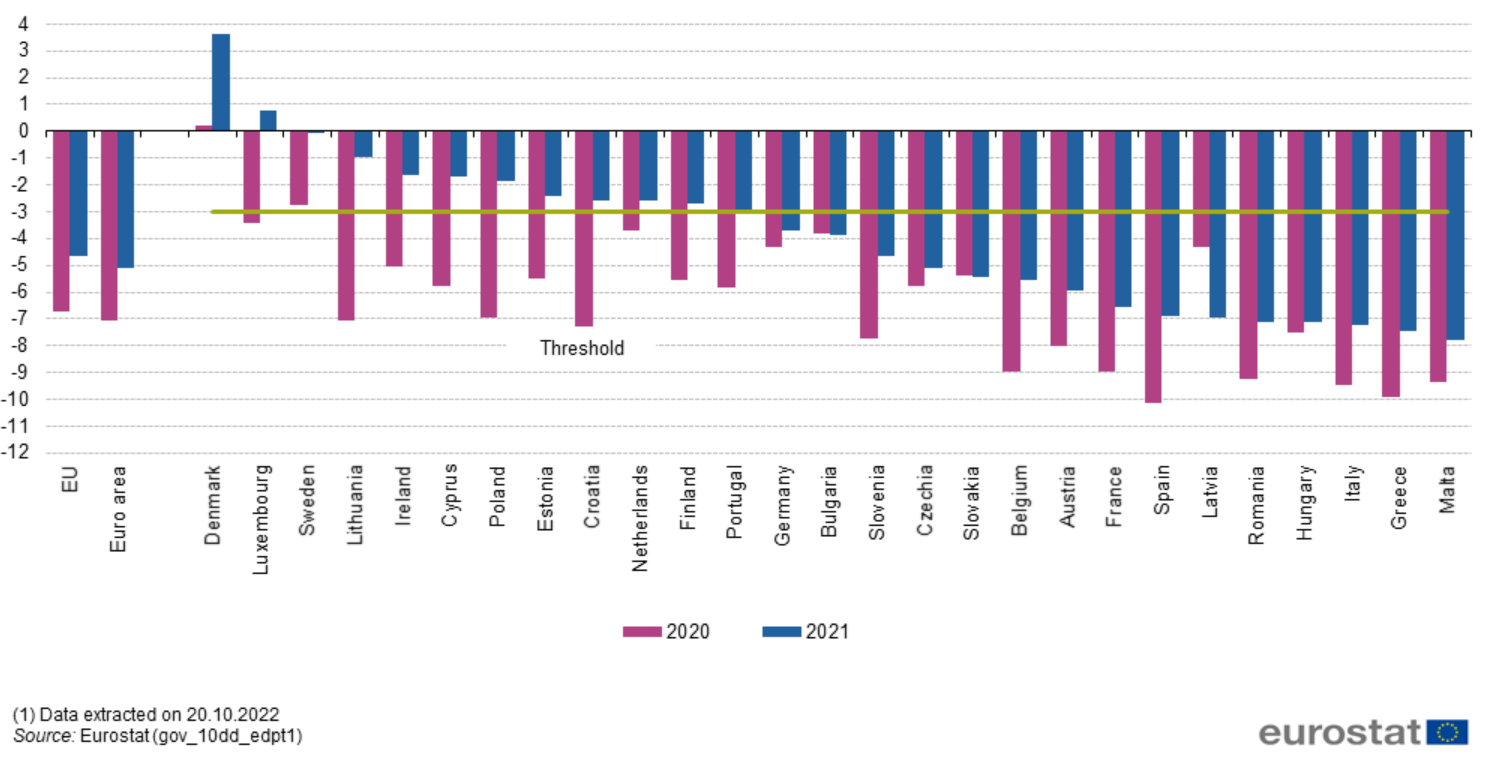

Last year, 14 EU countries had debt-to-GDP ratios in excess of 60%, while 14 Member States violated another key EU requirement of running budget deficits less than 3% of GDP.

Total government debt of EU Member States as a percentage of GDP. Credit: European Commission

Budgetary deficits of EU Member States as a percentage of GDP. Credit: European Commission

"These [new] guidelines will enable us to work together to reduce debt, strengthen our economies and lay the foundations for our future prosperity and stability," said Commission Executive Vice-President Valdis Dombrovskis at a press conference on Wednesday.

More flexibility, but also more enforcement

In a press release, the Commission stressed that, although "more scope would be given to Member States for the design of their fiscal trajectories", nevertheless more stringent EU enforcement tools would be implemented in order to "ensure delivery."

In particular, the Commission noted that financial sanctions imposed on fiscally non-compliant Member States would be lowered – hence rendering them ''more effective'' – and that ''EU financing could also be suspended when Member States have not taken effective action to correct their excessive deficit."

Moreover, under the EU’s new scheme, countries which violate the bloc’s fiscal rules would need to commit to a four-year (or, in some cases, a seven-year) expenditure path, which would require approval from both the Commission and European Council and whose implementation would also be ''continuously monitor[ed]" by the Commission.

Each country would, however, be individually responsible for designing its own debt-reduction trajectory. Moreover, in contrast to the current system, countries could in some cases be permitted to temporarily increase their fiscal deficits and debt burdens in the short-term in order to boost overall economic growth in the medium-term (i.e. within the next 4-7 years).

Related News

- Belgian federal budget feels weight of war in Ukraine

- Commission calls for freeze of budget deficit rules

Although many Member States welcomed the flexibility of the new scheme, some – most notably, Germany – were not so enamoured of it.

"A single monetary union also needs single fiscal rules,'' German Finance Minister Christian Lindner said. "Therefore, there cannot be a unilateral relaxation or creation of additional scope for assessment."

The EU’s current debt and budgetary limits – neither of which are likely to be altered for the foreseeable future – were enshrined into European law in the Stability and Growth Pact in the late 1990s, but were temporarily suspended during the Covid-19 pandemic. They are scheduled to re-enter into force in 2024, by which point the EU hopes its new scheme will already have become law.