It’s still a long way off, but five Belgian cities are already making plans for 2030, when one will be selected as European Capital of Culture, sharing the role with Cyprus. The five Belgian cities in the running are Brussels, Ghent, Leuven, Kortrijk and Liège.

The competition is already heating up, with the five laying out their charms as if for a beauty contest. The winner will then earn a title that they can brandish well beyond their 12 months as the culture capital – as well as the tourist money that will doubtless flow in.

But first, a recap on what the cities are vying for.

The idea of a cultural capital was launched in 1985 by Greek Culture Minister Melina Mercouri, backed up by her French counterpart Jack Lang. It was a bold plan to make the European Economic Community (as it was then) into something deeper than a simple economic union, by anointing a city as a beacon of culture.

In the early days, the jury chose historic cities packed with culture, beginning with Athens in 1985, followed by Florence, Amsterdam, West Berlin (the Wall was still up) and Paris. It all became a bit predictable.

Then came a surprise. Glasgow was picked as the capital in 1990. The run-down Scottish city with the motto ‘Glasgow’s Miles Better’ had to work hard to prove it deserved the title when its old rival Edinburgh might have seemed a more obvious choice.

Robert Palmer, director of the Scottish Arts Council, was appointed festival director. He started work in 1987 on a year of unique events that brought Luciano Pavarotti, Frank Sinatra and the Rolling Stones to the city. The programme included a theatre performance in a shipyard, the largest free rock concert ever organised in Scotland and a choir of 1,000 locals.

“It was a powerful example of what we now know as culture-led regeneration for cities,” Palmer recalled. The year of culture bred numerous initiatives, including the regeneration of the Merchant City quarter, the creation of the Glasgow Film Office and the City of Architecture and Design year in 1999. “Now every city in the UK has this, from Manchester to Sheffield and Cardiff. Cities across Europe, too - Rotterdam, Barcelona, Lille - and newer cities across eastern Europe,” Palmer added.

The Glasgow experience transformed the official thinking about EU cultural capitals, with some 200 reports written about the year, to say nothing of hundreds of articles.

One of those reports was written by Palmer himself. Known as the Palmer Report, the 2004 survey proved that the cultural year could promote urban renewal and quality of life as well as encourage cultural initiatives.

Antwerp’s lead

When Antwerp was picked as the first Belgian capital of culture in 1993, the city deliberately set out to follow the example of Glasgow. Antwerp mayor Bob Cools launched an ambitious urban plan that involved renovating old industrial districts along the waterfront. I was one of a group of journalists taken on a bumpy helicopter ride above the city to survey the scale of the masterplan. Thirty years on, the plan is still shaping urban policy along the waterfront.

Then Brussels got its chance. It held the title in 2000, but as it was the millennial year, the EU decided that the honour had to be shared among nine (yes, nine!) cities. Brussels had to share the title with eight other cities that each might have merited a year to itself (Prague, Avignon, Bologna, Krakow, Santiago de Compostela, Helsinki, Bergen and Reykjavik).

The 'Zinneke Parade' in Brussels

Brussels did its best to be bold. It persuaded Robert Palmer to move from his Glasgow base to run the project. But the year was doomed from the start by the complexities of the local administration. Unlike Antwerp, with its one mayor, Brussels has 19 separate communes, each with its own culture team. The commune of the City of Brussels, representing the old centre, was the official capital of culture. I remember some of the early meetings in La Bellone theatre when the organisers tried to agree on a plan. It was, frankly, a mess.

But there was one unexpected project that worked out well: the Zinneke Parade, named after the old Brabant word for a stray mongrel dog. Inspired loosely by the mediaeval Ommegang, the street parade brilliantly managed to capture the complex, multicultural identity of Brussels. Drawing people of all ages and backgrounds from every corner of the city, it created a powerful sense of belonging.

More than 300,000 people – three times the expected number – turned out on a rainy day to watch 4,000 participants in five separate parades converge on the city centre. It was such a success that the city decided to make it a biennial event. “The Zinneke virus got under people’s skin,” according to its genial first director, Marcel De Munnynck.

The Zinneke organisation went on to lead a nomadic existence, moving from one derelict building to another. By 2002, when the second parade was organised, the team was based on the top floor of the old Anspach shopping centre. On the day of the press conference, the lift broke down. ‘What is this – a squat?’ asked a Télé Bruxelles camera operator as he lugged 20kg of equipment up six flights.

The Zinneke is now bedded down in the city’s cultural calendar. The organisation currently operates from an old printing works where it serves as a model of sustainability and ecology. And after more than 20 years, the parade is still faithful to its original focus on the city’s diverse, cosmopolitan identity.

Split titles

The millennium year marked a new beginning for the EU’s cultural capital project. Since then, the title has usually been shared by two or more cities. In 2002, Bruges sat alongside Salamanca. The small Flemish city made a determined effort to create a legacy by building a new concert hall, as well as several small-scale architectural projects. But locals failed to appreciate Japanese architect Toyo Ito’s contemporary pavilion on the Burg square. Dubbed the car wash, it was demolished in 2013.

In 2004, Flanders had the title again, or at least, historical Flanders, as the northern French city of Lille shared the role with Genoa. It was a unique opportunity for the city to rebrand itself. “We are fed up with our region being seen as grey and black,” declared Lille mayor Martine Aubry. The city’s programme was teeming with cool and creative ideas ranging from artificial trees suspended over a street to a tiny mobile restaurant that seated four diners.

In recent years, cultural capitals have often been small and relatively obscure cities. In 2015, Mons in southern Belgium got its chance to make a mark, along with Plzeň in the Czech Republic. But Mons got one big thing wrong. The planned new railway station, designed by Spanish architect Santiago Calatrava, was not finished in time (it is still not completed – see separate article).

Brussels is now back in the running for a second time. But it faces strong competition from four other Belgian cities, each trying to figure out a winning formula.

How a city gets to be cultural capital is a long bureaucratic process. Ten years ahead of the event, the EU selects the country to provide the cultural capital – usually an EU member, although Turkey, Norway and Iceland have been involved. Eligible cities decide if they want to compete. They submit a preliminary proposal to an EU panel of cultural experts, which then draws up a shortlist, asks for more detailed plans, and finally picks the winning bid.

Brussels again?

Brussels is now back in the running for a second time. But it faces strong competition from four other Belgian cities, each trying to figure out a winning formula. The Belgian candidates have to send in their initial plans by the end of 2024, with the winner announced the following year.

Brussels has strong claims to the title. It already named two people to serve as directors: Jan Goossens, who used to run the Flemish royal theatre KVS, and the French-speaking RTBF anchor Hadja Lahbib – although the latter has since been appointed as Belgium’s Foreign Minister. They gathered a ‘reflection team’ of people with very different backgrounds, including the climate activist Anuna De Wever, urbanist Eric Corijn and Congolese photographer Sammy Baloji.

By 2030, the city will have a landmark new contemporary art centre KANAL, due to open next year in a former Citroën garage. It will also have a vibrant arts hub next to the canal in Molenbeek where several cultural organisations have already settled into old industrial buildings. And hopefully, the city will have resolved the problems in its traffic circulation plan so that Brussels can showcase itself as a model ecological city of the 21st century.

The Kanal art centre in Brussels

The 2030 team has already set up a website to state their aims (brussels2030.be). They have designed a neat logo (which you can tweak online, if you want). The organisers say they want to ensure the project benefits urban planning, sustainability, diversity, democracy and equality. And they want to involve Brussels residents in the planning. “We are you,” they claim.

The plan is radical. They say they hope to transform Brussels with artists, thinkers and culture as the driving force. But not only that. “We want to become a capital for all Europeans,” the organisers say. “A laboratory for intercultural and multilingual coexistence, but also for the ecological, democratic, social and decolonial revolutions that await us.”

But there are some hurdles to overcome. If Brussels is chosen, it would be the first city to be appointed twice. Moreover, it would mark a departure from a trend that has seen small cities winning the title. This year, the three cities sharing the title were Luxembourg’s Esch-sur-Alzette, Kaunas in Lithuania and Novi Sad in Serbia.

It might be that Brussels is too big to succeed. And again, the EU might be reluctant to give the city a further role on top of hosting the European Commission and the European Parliament.

Then there is the timing. The country is gearing up to mark 200 years of Belgian independence in 2030. The EU title would fit perfectly with the anniversary, the organisers argue. They point out that the federal government plans to renovate the Cinquantenaire site to mark the anniversary. Created in 1880 to mark 50 years of Belgian independence, the site includes several museums, including the remarkably rich but sadly neglected Royal Museum of Art and History.

Meant for Ghent

But the EU jury might decide that Brussels will be too focused on national identity in 2030 to pay much attention to its role as culture capital. That might allow the other four cities to shine.

Ghent launched an impressive campaign earlier this year when it set up a group of 30 engaged locals (‘The 30 of 2030,’ they were named) to develop strong projects.

The Ghent campaign is led by a team of six, including historian Tina De Gendt and musician Frederik Sioen. They are banking on the fact that Ghent already has world-class culture. “Artistically, Ghent ranks among the world’s top cities,” claims Milo Rau, the acclaimed Swiss theatre director who has served as NTGent’s artistic director since 2018. “Here you can find theatres, cultural centres and ensembles of international standing you would normally expect in larger cities.”

Ghent's recently refurbished Winter Circus

The renovated Winter Circus is the most recent sign of Ghent’s cultural ambitions. The vast circular building once staged circus shows in front of more than 3,400 spectators. An abandoned ruin for many decades, it has been brilliantly restored as a concert hall combined with offices, a restaurant and a bar. Due to open next year, it would make the perfect hub if Ghent became Europe's culture capital.

Stairway to Leuven, ripe for Kortrijk,

The city of Leuven also believes it has what it takes. The organisers of its bid quote a 2017 EU study that looked at the makeup of a cultural and creative city. “The ideal city should combine the cultural facilities of Cork, the attractiveness and smart jobs of Paris, the intellectual innovation of Eindhoven, the new creative jobs of Umeå, the human capital and education of Leuven, the openness, toleration and trust of Glasgow, the local and international connections of Utrecht and the excellent policies of Copenhagen,” the study says.

The organisers claim that Leuven – voted European Capital of Innovation in 2020 – ticks all the boxes. They point out the city’s many cultural assets, including the arts network 30CC, the M Museum, the renovated STUK theatre complex and the emerging Vaartopia quarter on the site of the old Stella Artois brewery.

Leuven's Vaartopia quarter

Leuven’s director of culture Piet Forger points out that the role of capital of culture has changed over the years. “In the early years, it was about city branding, tourism and infrastructure,” he says. “But it now acts as a launch pad to create a better future for the city.”

When asked if Leuven might be too modest for the role, the city’s alderman for culture Denise Vandevoort notes that the title is often awarded to smaller cities. “It’s now time for Leuven to stand up and take its place in the world,” she insists.

But if Leuven can make it as a small city, then Kortrijk also stands a chance. The former textile city might seem an unlikely choice, but the city has already launched a plan called DURF2030 (durf2030.eu) that aims to put together a programme of 2,030 projects. “It can be anything,” says project director Katrien Voet. “The only requirement is that your project has to give something back to the street, neighbourhood or city.” But maybe 2,030 is a bit too ambitious, given Glasgow organised 400 events.

Liège raises standards

And what about Liège, the only Walloon city in the running, after Charleroi dropped out of the contest? The gritty former industrial city might not seem an obvious candidate. But Liège has a beautiful fine art museum, a cultural centre in a former swimming pool and a dynamic university. The city has hosted big events in the past, including a World Fair in 1905 and an International Water Expo in 1939.

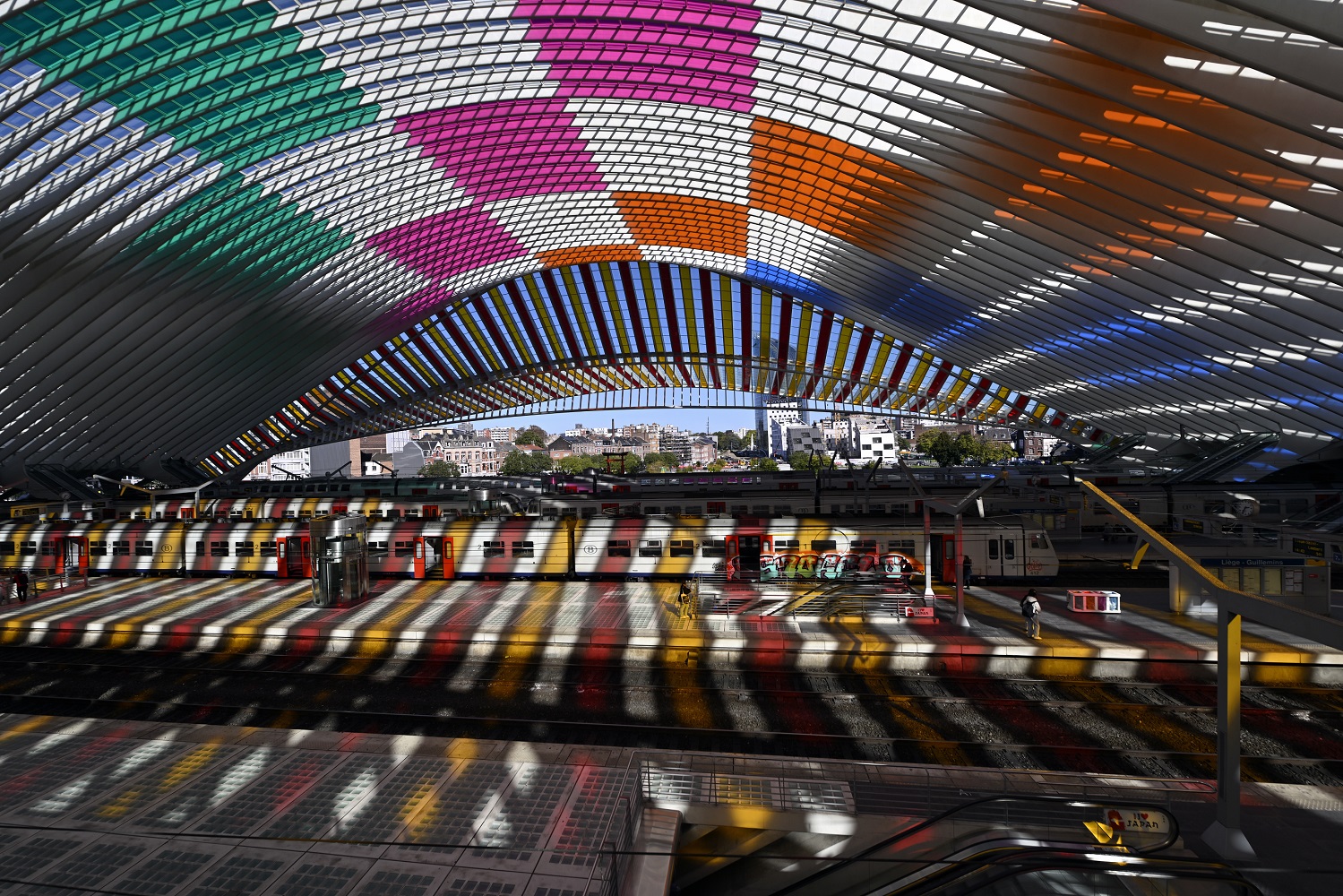

Anyone who doubts Liège’s ambitions should take the train to Liège-Guillemins. The futuristic station designed by Santiago Calatrava has been transformed by a monumental multicoloured artwork by the French artist Daniel Buren. Stéphan Uhoda of the Uhoda Group, the main project sponsor, say one of the main motivations in developing the project was to promote our city on the international cultural scene.

The futuristic Liege-Guillemins railway station

But Liège has an unfortunate history. The city tried to apply to become the Capital of Culture in 2015. The arts sector came up with a deluge of exciting ideas. But local politicians lost their nerve and the city abandoned its bid, leaving Mons to take the title. A few years later, Liège applied to organise the 2017 Expo International, but it was beaten this time by Kazakhstan’s glitzy capital Astana.

The plans coming out of Liège are still vague. No need to panic, one local politician has argued, the city has until the end of 2023 after all. But the other four cities are not waiting around. Liège might need to get moving fast if it wants to impress the jury.

At the end of the day, the city that wins in 2030 might be the one that promises to recreate the excitement that infected Glasgow in 1990. It was, Robert Palmer recalled, like managing a volcano. “Overflowing with the hottest talent and the most incredible excitement that could be imagined at that time. That creative volcano continues to erupt even now, and perhaps evermore.”