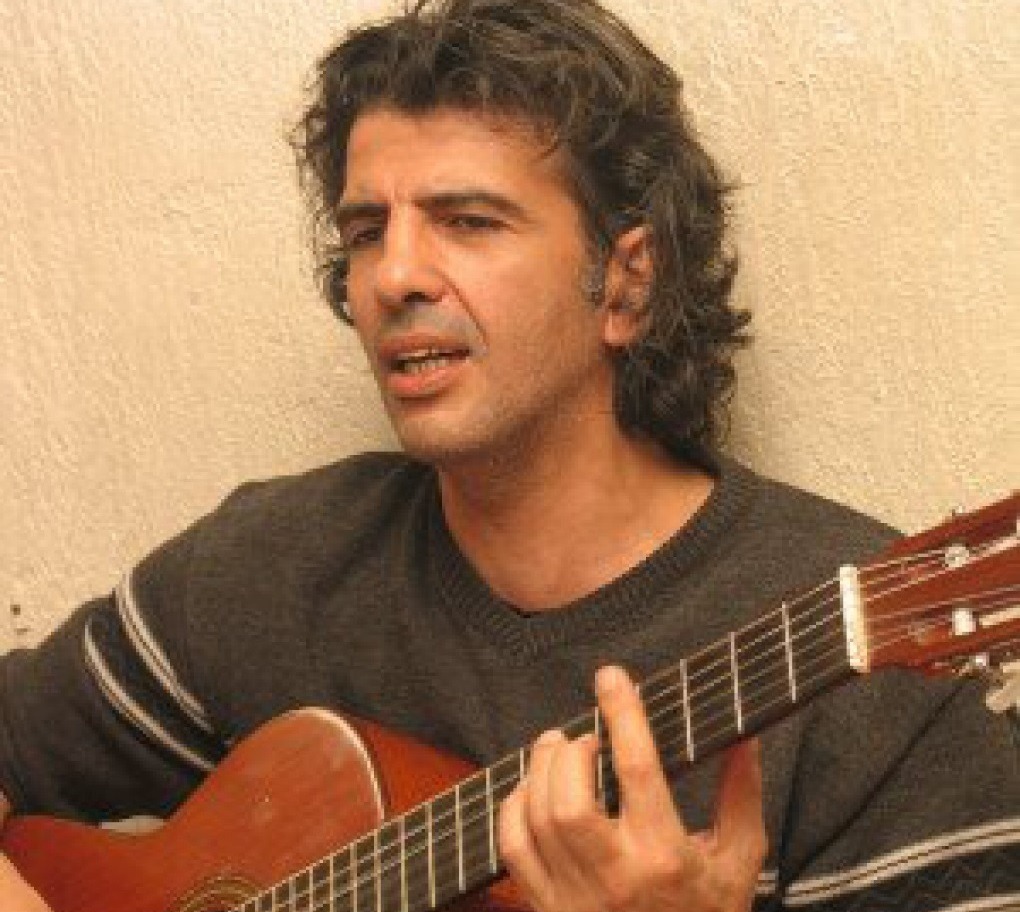

Basel Khalil is a Syrian musician, composer and lyrics writer. Born in Damascus in 1962, he left Syria in 2013 following the civil war. After having spent a total of three years in Egypt and Turkey, he has finally arrived to Belgium to build a better future for himself and his family.

Q: Can you tell us about your life in Syria before you decided to leave?

A: I was born in Damascus and started to play music from an early age. In high school I specialised and took extra music lessons. In 1979, I went to Moscow and studied for a degree in electronic engineering. At the same time I also went to the philharmonic institute and learned how to compose and make music. Of course I also learned Russian during this time. When I returned to Syria, I had to join the army. I was placed in the Army’s musical band because of my background. Once I finished the army, I got work at the Russian cultural centre in Damascus as a music teacher. Our level was very good and I had many students.

Music is truly a passion for me so it was fantastic to work doing what I loved. I didn’t make a lot of money but I was very happy and it was very rewarding to see the joy in the eyes of my students. Besides teaching I also wrote and composed music for films and theatre. It was during this time that I met my wife Initisar, which means victory in Arabic. We both had victory in finding each other. We have two sons Taim and Rasel. I also have a daughter, Maya, from my previous marriage.

Damascus, 2010

Q: What is the general opinion of the citizens in Damascus about the situation, the neighbouring Arabic countries and the West?

It’s not an easy question to answer. I think it is important to look at and understand how it was before the revolution and current fighting started. Already when I was born, we had many problems with the government. We lacked basic freedoms and couldn’t do anything without the permission of the government. There was always bureaucracy which for us is synonymous with corruption. If you don’t pay you don’t get anything. It’s similar in many Arabic countries.

When I was younger, I joined the communist party but I quickly realized that it was the same as the government and I left. So this was the situation already before the war. There was much internal frustration and anger and it was only a question of time for something to spark all the violence. We saw what was happening in Tunisia, Libya and Egypt so people in Syria started to also go out on the streets and voice their opinions.

Personally I was very happy when the revolution started. I thought freedom would come and that we would get more rights. It felt like a dream. But the dream slowly became a nightmare. And the government started to arrest and kill protestors.

I remember when it all started in Dara. Some schoolchildren wrote what they saw on TV. The government officials came to arrest them and put them in prison. They were only 11 - 12 years old. We knew from witness accounts that the kids were being tortured in the prisons. A common practise is for example to remove the nails. When the parents asked when their children could return home, the answer from a government official them was; “Give me your wife and I’ll make you better children”. Up until today those kids are still missing. Maybe some are dead while others are still in prison. This was really what started the revolution.

The initial protests were just vocal and not violent. Then other players started to interfere. Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Iran, each with their own agenda, fearing that Syria would fall to one or another country’s influence. Now there are too many factions and organisations fighting each other in Syria and the revolution is finished. The protestors are either arrested or have fled the country. I think that people in Damascus do not have any preference to any side really and those who are still there are too poor to flee. Syria has become a political game arena.

Q: At which point did you decide it was time to leave?

After the revolution started, I observed how things weren’t going right and I had many friends who either distanced themselves from the government and some who instead got closer to it. One of them sent me a letter and asked me if I could work for the government to compose and write pro-government songs. I couldn’t do it. It was going against my heart and myself. I hated the government. Following my answer to him on my decision, I felt the danger and this really triggered me to think more seriously. I said to myself that I had to leave.

I remember how I put one of my students in charge as teacher of my class and ran away. After one month, people were still wondering where I was and kept asking him. I had fled alone to Egypt with the aim to later bring my family. When you have a family you can never rest. You want to take care of them. To give them a better future.

Q: What was your experience like in Egypt and Turkey?

Egypt is a big country. It is very different from Syria. In the beginning it was hard to find work but after some time I was hired at a famous musical institute called Guitara. I was of course happy about it but with time my mood changed and I wasn’t so sure if it was the right thing to stay there.

Egypt as a country also had a lot of instability with its own revolution and with the Muslim Brotherhood. It was also very religious for me and my family. My wife and kids were mostly at home. My wife had to always wear a veil or niqab when she went out. I wanted my kids to have a normal education that included music and regular subjects, not just religion. In Egypt there were only religious schools available to them. By now my kids haven’t been to school for three years and it concerns me a lot.

So I started to think about going to another country and I actually didn’t have many options. The only country I could go to was Turkey. All Arabic countries had closed their doors. So after a year and a half in Egypt, we left to Istanbul.

In Istanbul I got an opportunity to work for a radio. It was a media that was for the opposition against the local government and they received a lot of support and money from Europe. I was excited about this new opportunity. However the editor didn’t dare to say much. The atrocities and killings in Syria were censured for example. I don’t think many people listened to it and I discovered that the station was corrupt and just set up in order to receive money from Europe. I couldn’t identify myself in this corrupt system so I parted from it.

Dömsek, the group that Basel started in Istanbul. Picture from 2015

Financially, those were hard times for me and for the first time in my life, I went to the streets to play. It wasn’t an easy thing for me to do because in Syria we didn’t have such a culture. It felt like begging for me. I started to receive lots of money from wealthy tourists from the Gulf region. And surprisingly it became popular and I was joined by more musicians. We formed a group called Domsek which means something like “good smell” in the Syrian language. We blended Turkish and Syrian tunes and became more and more popular. For about a year and a half we played music every day on the streets. After some time we had made a name for ourselves and started to get invited to play concerts and at important events.

Q: How did you come to Europe and finally to Belgium?

Well, I was thinking of Europe because I was thinking of my family. Me and my wife discussed how we could give our children a better future. And if I would be allowed to work and live in Europe, my family would also be allowed to follow me. So I started to collect money and decided to come here by myself and then later be joined by my family. They are still in Istanbul waiting for news.

I knew the way would be dangerous but I have always trusted my destiny and I said to myself that it would be ok. But having done it now, I don’t know if I would do it again after what I experienced. Not because I am scared for my own life but if something would have happened to me, three more lives would be affected as I am responsible for my family.

When I entered the boat, I saw many children and babies on board. It was some kind of inflatable boat and didn’t look very safe. All together we were around 50 people inside. I remember sitting and looking at the people and everyone was afraid. I started to calm the kids but I knew I also had lots of fear. I know I can swim but all the little children couldn’t and it wouldn’t have been easy to save them if we fell in. We got water coming inside and were working all the time to throw it back out. During the whole journey the children screamed.

This wasn’t the only thing that we worried about. My friend Amid whom I was travelling with had already done the journey once. He told me about criminal gangs from Albania who would come with big boats and pretend to help. They would throw a rope to get your boat close to them and then get inside and ask for money and documents. After they would pull out large knives and cut holes to sink your boat and let you drown. It was horrible stories. Amid told me that he managed to swim and get to safety back in Turkey. These stories were one of the reasons why I was afraid to bring my family on this kind of journey. If I would have taken my kids to experience this, it could traumatize them for the rest of their lives.

We arrived to Lesbos island in Greece. It was about 18 km to the main town Myteleni. No taxis or buses would take the refugees because they were afraid to get in trouble with the police. So we had to walk. Many walked in the same clothes that they wore in the boat. Me and my friend got out of the group and caught a taxi. We showed the taxi driver our Turkish documents and he accepted us as passengers. We are quite pale skinned and don’t look so Arabic - maybe it helped. As we were driving to the city I saw so many refugees, families and kids walking and it made me cry.

Once we arrived to the refugee camp in town we were shocked. There was a lot of chaos and a fire had broken out. Police struggled to make order as people were waiting to get the documents needed to continue their journey. We were very lucky to receive the documents quickly and the same day at 11pm we got on a boat that took us to Athens.

In Athens I bought a guitar and me and Amid then continued to Thessaloniki by train. On the way we continued to see lots of refugees. Many wanted to get on board the train but only smaller groups of people were allowed at a time. It was very cold during this period and people had to wait outside at the train stations. We felt bad for them but happy that we could get on so quickly.

From Thessaloniki continued got to Serbia. There we had to walk many kilometres under the rain. Whenever we gathered with refugee groups, I’d take the guitar and play. It cheered people up and everyone could forget about their problems. A Belgian journalist saw me and made a small article about it.

Basel plays the guitar in a camp in Kanjiz, Serbia in 2014

Our target was to get to Hungary and from there reach Belgium. In Hungary, we were told to be careful because if police caught you, they would take our finger prints and not allow us to continue. They never took mine and Amid’s. I think our guitar saved us. We didn’t look like refugees but perhaps more like tourists. Once a policeman did catch us and I showed my Syrian passport. But he said “go on, go on”. We felt very lucky. Normally he should have taken us to a compound.

In Hungary we walked for many kilometres. We didn’t trust the taxi drivers because of stories circulating that they stole the refugees’ money or called the police. But finally we were so tired that we just got on board a taxi driven by an old man. It was night time and we couldn’t see anything and I remember that he drove very quickly. I was worried about his driving and wasn’t sure if he actually knew the right way. I showed him the GPS on my smartphone but he wouldn’t have any of it and said he knows his country. I was right or rather the GPS was right, because we had driven past our target Budapest but finally arrived to the capital after some detours.

In Budapest many people waited at the train station to take them on to Germany. And once our train finally arrived to our target destination Brussels, we camped outside the Brussels North station. There, we waited for about ten days to be registered at the immigration office. After that they took us by bus to a camp in Lakenen.

It is a bit isolated from the city but we have wifi and I’ve managed to start to work. I paint the walls. I’m allowed to be outside the camp for ten days per month. I’m now waiting to get my second interview in order to get documents that would allow me to stay here.

Q: Did you notice any radicals among the people along the route?

Those who come here are running from war or don’t accept their governments. I didn’t see or hear anything about it. They have to be quiet I guess. We can’t know everyone. Some might have been involved in the fighting but we don’t know. If there are people with bad intentions or radicals among the refugees, they of course wouldn’t be open about it.

Q: What can you recommend the Belgian immigration authorities?

I came here because I was told that Belgium provides the documents quickly but now I see that it’s not so easy. I have been in this camp for over two months now and I am still waiting for the next interview. I have no idea when it will happen. I think there is not much logic behind the process. Some people have for example arrived after me and have already received their papers.

There is not a lot of clear information available about the process. I know that lots of people have come and that the capacity is limited to take care of everybody but I think that if things were a bit clearer on who is allowed to stay, it would save a lot of time and uncertainty. For example, if they said that they only accept people from countries with civil war. I know of people who have come from countries with no war.

Q: How do you remain strong during this time of insecurity in your life?

You have to wait and be patient. Thoughts of my family keeps me strong and it’s the only thing that I care about now. Yes, sometimes when I think about the situation and all the waiting I think I’ll go crazy. I go inside a room and just want to scream. But everybody in the camp is in a bad situation and some have gone through very difficult experiences in their home countries, and many have bigger problems than me, so I manage to compose myself.

Picture from the camp in Laneken outside Genk in Belgium, October 2015

I also play a lot of music. This is my passion and I see how it can connect people and make them happy. I play in the camp a lot and it calms us down. It’s like a universal language that everyone can understand. I know that I must be strong for my family. I have a lot of responsibility as only I can bring them here. It gives me hope and I believe everything will be fine. I trust my destiny.

The Brussels Times