The Italian Government has denied illegally deporting refugees to Greece on private commercial ships, in response to a letter sent by the Council of Europe (CoE) Commissioner for Human Rights Dunja Mijatović, who is also asking Italy to withdraw a new decree that limits NGOs' ability to rescue asylum seekers and refugees at sea.

In a letter to the far-right Italian Government led by Giorgia Meloni, the CoE Commissioner has requested an explanation for the allegations the government is carrying out illegal pushbacks of refugees between Italy and Greece on private commercial ships, which the Italian Government has claimed is "without foundation."

In response, Italian Interior Minister Matteo Piantedosi admitted the practice in a statement to the Commissioner, justifying it under a 1999 bilateral agreement with Greece – which does not apply to asylum seekers and refugees – and is denying that those deported were refugees.

The Italian Minister insisted that only "irregular foreigners who do not intend to apply for international protection are readmitted to Greece, by entrusting the carrier with a special report delivered to the ship's master." This claim contradicts the evidence published by the Lighthouse Reports, which evidenced Iraqi, Syrian and Afghani refugees having been transported via commercial passenger ships.

Piantedosi also rejected the evidence presented by the reports that minors were deported under this norm, adding that only those travelling with their family were transported. The Lighthouse Reports verified three cases in which under-18s were transported from Italy to Greece, with one case of a 17-year-old alleging that he was illegally sent back without even being asked about his asylum claim.

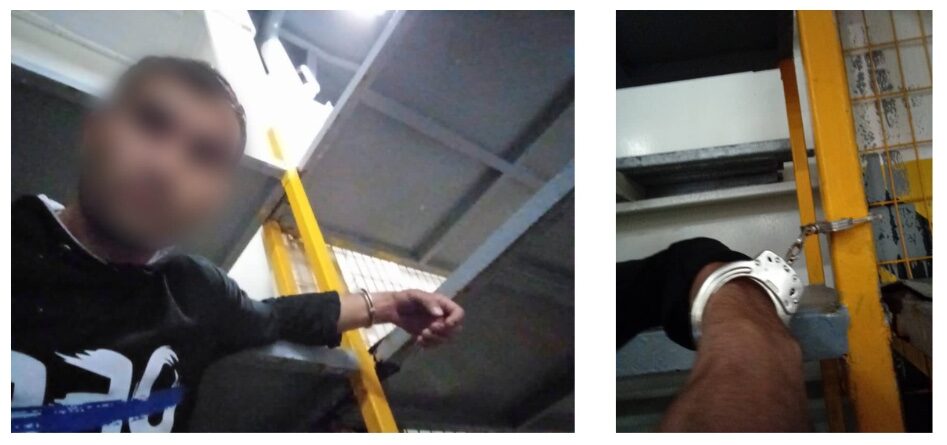

Selfie of an Afghan asylum seeker detained on a commercial ship. Credit: Lighthouse Reports

Regarding the conditions of deportation suffered by many refugees deported via private commercial ship, the Italian Government has shirked its responsibility onto the private ship. "As pointed out that in the execution of the Italo-Greek Agreement, the transport is carried out by the carrier, therefore it is not possible to report on what happens on board the ship," Piantendosi said.

NGO decree

A new law said to hamper NGOs' search and rescue operations has been put under the Council of Europe's microscope, also believed to be in breach of Italy’s obligations under human rights and international law. "I am concerned that the application of some of these rules could hinder the provision of life-saving assistance by NGOs in the Central Mediterranean and, therefore, may be at variance with Italy’s obligations under human rights and international law."

The Decree demands rescue vessels to reach, without delay, the port assigned by the Italian authorities for disembarkation.

However, it risks being applied in such a way that it could prevent effective search and rescue by NGO vessels, the Commissioner writes. "As has already happened in practice, the provision prevents NGOs from carrying out multiple rescues at sea, forcing them to ignore other distress calls in the area if they already have rescued persons on board, even when they still have the capacity to carry out another rescue."

"The power of the government authorities responsible for search and rescue at sea cannot be circumvented, nor can the rules on border control and immigration," responded Piantendosi. "The new rule aims to avoid the systemic recovery of migrants in the waters off the Libyan or Tunisian coasts, in order to bring them exclusively to Italy, without any form of coordination."

Related News

Furthermore, the Meloni government was also reprimanded for giving NGO vessels distant places of safety to disembark people rescued at sea, such as ports in Central and Northern Italy. "The decree and the practice of assigning distant ports to disembark people rescued at sea risk depriving people in distress of life-saving assistance from NGOs on the deadliest migration route in the Mediterranean," writes the Commissioner.

The Italian Government has responded by outlining that the choice is based on the “unavoidable need for a fairer redistribution between regions,” not so much of migrants, who they claim are usually transferred to reception facilities throughout the country, but rather to ease the pressure on the reception entities in Sicily and Calabria.

“This objective, however, could be met by swiftly disembarking those rescued, and making sure that alternative practical arrangements to redistribute them to other parts of the country are put in place,” Mijatović wrote.