The year is 1969. Rock music hits its golden age and yet it is still very much of an Anglo-only phenomenon. The British invasion only happened in the States. Elsewhere, that weird music is seen, at best, as an Anglophone oddity and, at worst, as a symbol of its imperialistic decadence. That is, until a little country decided to open its doors to this new music and served as a steppingstone for British and American artists to the European mainland. And that country was Belgium.

Of all the weird and unusual stories about our country, the deep-rooted relationship between Belgium and classic rock music is by far the most overlooked. And still, it is a defining trait of Belgian society and played a major role in propelling this music into a worldwide phenomenon. Here is the story of how Belgium saved rock and roll.

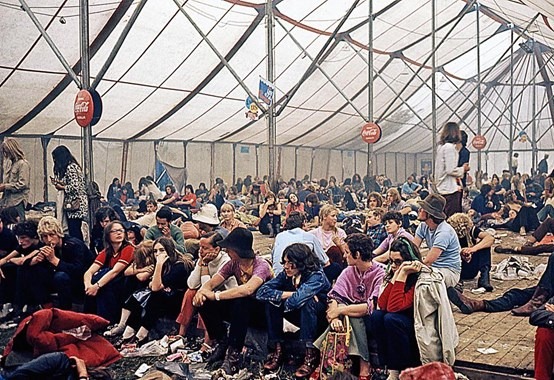

1969 - Woodstock gathered half a million rock fans, as Joni Mitchell sang. Later on, the British answer to this American festival was the Isle of Wight festival. The logical step after those two legendary events was a mainland European event. And it happened here, in Wallonia: the phenomenal Amougies festival, three days of unprecedented rock lifestyle, and the only time that Frank Zappa joined forces with Pink Floyd on stage. The Internet video still leaves fans of both acts in awe.

This was only the beginning. Over the next few years, Belgium would offer Genesis its first experience of international and would be a haven for Marvin Gaye. This passion for sixties and seventies music will linger forever, and today Belgium still rocks to its pace.

Back to 1969; a music festival - one that would later become the Amougies festival - was originally planned to take place in Paris, by then the biggest cultural hub of Western Europe. A magazine, Actuel, supported the idea of a big rock festival à la Woodstock and Wight. It was supposed to be organized in the massive halls of Châtelet in the centre of the city. It was named Festival Actuel after the publication and soon gathered an impressive list of potential performers.

But it was not to happen. France had just experienced the events of May 1968, and the Gaullist government was not keen on opening the doors of its capital city to a raging horde of long-haired hippies. Under pressure from the Interior Minister Raymond Marcellin (also the head of the French police force), Actuel moved its planned venue to the outskirts of Paris, then to the northern French countryside. Eventually the projected festival left the country altogether. In the end, the Festival Actuel was organized in Wallonia, next to the small village of Amougies in the province of Hainaut.

At that stage, the country has already shown an early interest in English-language rock music. A major actor of this little Belgian revolution has the evocative pseudonym of Piero Kenroll. This journalist, whose real name is Pierre Vermandel, is credited with pioneering rock journalism in Belgium. In the sixties, he was a Brussels Fonzie, sporting a black leather jacket and gathering friends to break musical boundaries.

“At that time”, he tells me, “Walloon culture was submissive to Paris. RTBF was instructed to only broadcast music that included accordion, to sound French. Then they started re-recording French translations of British or American pop songs, with an edulcorated arrangement, sung by French singers. My friends and I hated this and we organized a protest on Place Flagey, where this big building was the headquarters of RTBF at the time, demanding real Anglo music instead. When those French singers came in concert in Belgium, my friends and I would storm the audience and throw tomatoes at them”.

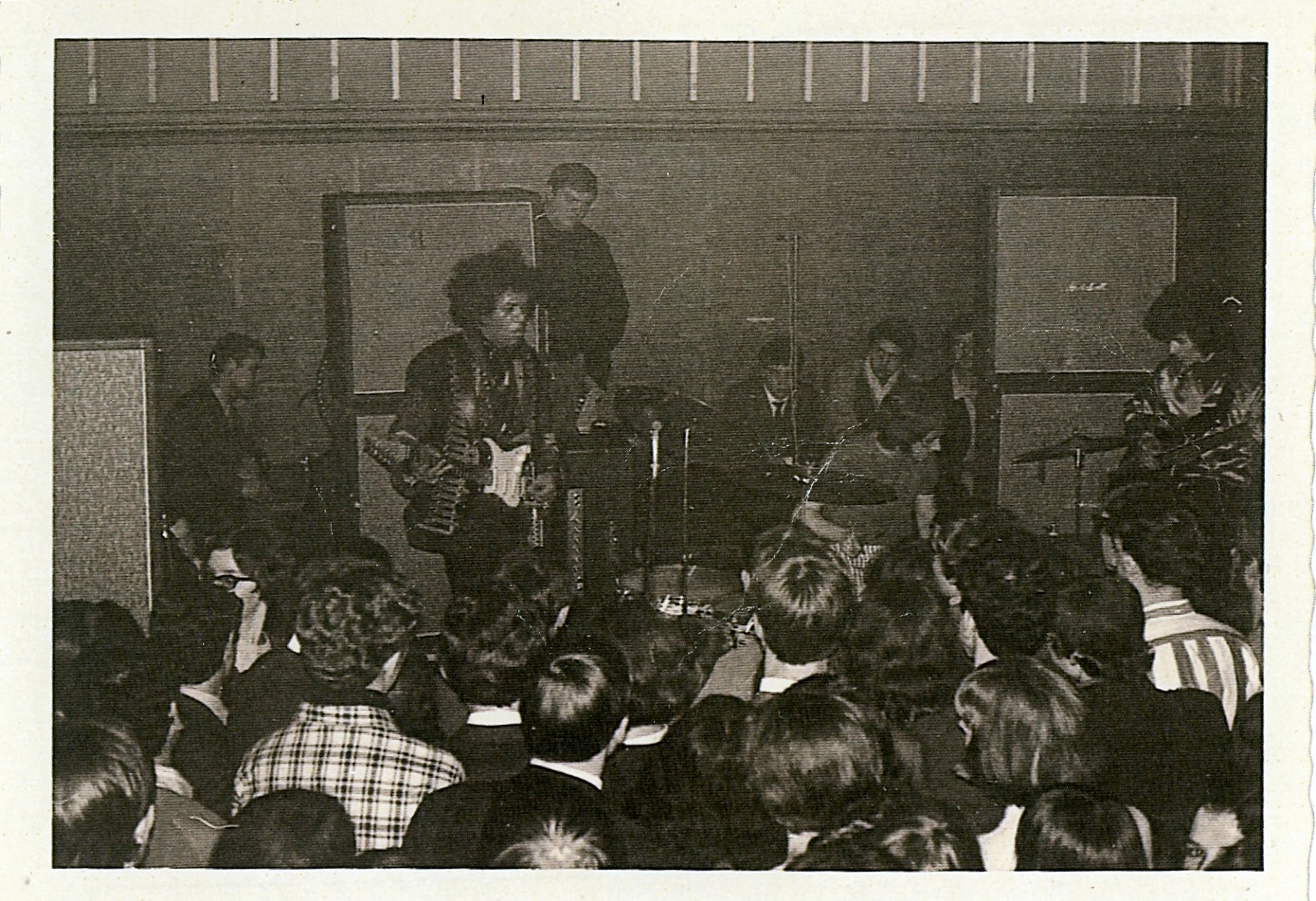

A few years earlier, in 1967, Hendrix did his first concert out of the USA in Belgium, in a small club in Mouscron, at the westernmost end of Wallonia. According to legend, the audience worried at him being late, only to discover the bouncer had denied him entry because he looked like a vagrant. Today, the small town organizes a guitar festival every year in homage to the guitar deity’s passage. The area of Mouscron and Tournai would grow to become a major hub for rock music. In the late sixties, the Moody Blues found shelter there, fleeing from their crazed British fans. In their peaceful Walloon retreat, they wrote the legendary album Days of Future Passed featuring their hit song Nights in White Satin.

Jimi Hendrix playing for the first time outside the US, in a small club in Mouscron, Belgium, March 1967

Hendrix passed by Brussels too. Sitting in a café on Boulevard Anspach, I can see the hotel where he stayed. In this very café, he met with journalists. On a coaster, he scribbled in psychedelic letters the sentence “Are you experienced?” The following year, this became the title of his most famous album. A picture was taken of him eating what looks like carbonades in a typical Belgian restaurant – a glass of beer and a tin dish for his fries, no doubt, Hendrix was there having a Brussels experience.

The coaster and the picture can be seen alongside countless memorabilia of rock in Belgium on a phenomenal online museum. The website “memoire60-70.be” is the work of Jean-Marie Valmont, aka Jième. In the seventies, he was an agent and witnessed all this. Today, he does a remarkable job of archiving and making this fascinating story available to all on his website. He confirms what Piero said, “The French had their own singers to promote, so they did not want to open doors to foreign singers. The Amougies Festival was the moment France missed its chance and Belgium took over. When I was an agent in the seventies, I was recruited by a Parisian company, and there I could never have organized a tour for British or American artists. Agents in France easily took 50% in fees, whereas in Belgium we only took 10 or 20%. Parisians recruited me because I spoke English, but they were not keen on using that skill, they lost their time in endless chats on Champs-Elysées about future plans that never happened...

“Things were more straightforward in Belgium. The fact that we had plenty of big cities, with campuses, all close to each other, also made it very practical to organize a tour that was profitable for the artists in every way. I still cannot believe I saw people in France closing doors to Pink Floyd or the Moody Blues...”

The most impressive testament to Belgium's role in exporting rock music is Genesis, the band that propelled Peter Gabriel and Phil Collins to stardom. It was little known in its own native England before Piero took note of their very first album in 1970 and saw the talent of these five young boys. “I phoned their producer and said, send them here. I'll guarantee television, coverage, and a full concert hall. They could not believe it, they barely had the money to pay for the ferry”.

In a book, Peter Gabriel related how they ended up sleeping in Piero's living room to save money. The band did their first television show ever on RTBF – yes, the first television performance of Gabriel and Collins was on Belgian TV. I was lucky to work with Franz Wenzel, a sound engineer with a long career on RTBF, who was on duty that day. “I remember at the time there was no ad hoc technology for recording rock bands on TV”, he told me, “and I had to fiddle around with whatever material I had available, to give a good rendition of guitars and organs. We were pioneering all that”.

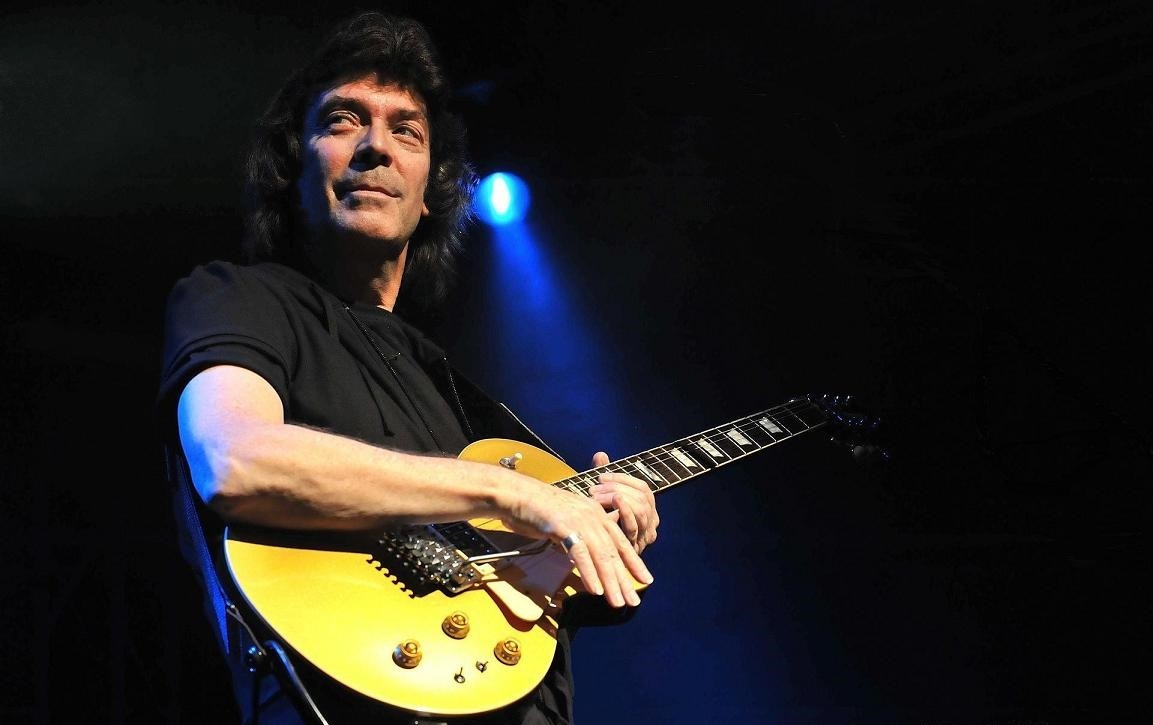

Genesis guitarist Steve Hackett talked to me about this Belgian experience with unabashed enthusiasm. “We arrived completely wrecked by a night on the ferry, and Piero and everyone at RTBF welcomed us so warmly, we never had this before. Piero was quintessentially Belgian, soft and gentle while very straightforward about what he wanted and what he liked, sensitive and enthusiastic, with wide blue eyes and an incredible influence as a journalist. Just what we needed.”

At that stage, Genesis had been struggling for some time to exist as a band. Belgium welcomed them in a cult concert hall called Ferme V, located at the edge of Brussels, where a big audience packed the hall in response to Piero's reviews. There were no loges and the musicians had to walk through the sitting audience on their tiptoes to reach the stage. “We were a band looking for an audience in a country looking for identity”, Steve says. “The permanent question about identity in Belgium made people remarkably open to a new sound and to the storytelling of our songs. There were no borders in the mind of Belgians. I felt like I was playing for individuals and not for people who had been told what to think”.

Piero told me of a similar conversation: “I met with Frank Zappa when he played in Brussels and he said we had the most open-minded audience he ever had. His wife, though, added that Brussels smelled bad...”

This love story is a long lasting commitment. Today, Belgium has an astonishingly high enthusiasm towards that era of rock music. Radio station Classic 21 solely broadcasts artists from the sixties and seventies, from the most romantic to the hardest guitars. They are not a niche station, we are talking about a public broadcaster, the very RTBF that once banned anything that did not have an accordion. Its success is constant and even crosses the language border: Classic 21 is the most popular non-Flemish radio station in Flanders. Its boss, Marc Ysaye, was once the drummer of Machiavel, a band hailed as the Belgian Genesis. He is seen as a central figure of classic rock in Belgium.

Steve Hackett, guitarist of Genesis, praised Belgium for launching their international career.

“We were one of the first countries to open our doors to Progressive Rock”, he says, “France was very protectionist at the time, and even today they are still busy discovering Genesis. Geography also played a role, we could listen to pirate radios like Caroline and Veronica, who were based in the North Sea and AFN, the radio of the NATO headquarters near Mons”. Jième also mentioned the ideal location of Belgium: “there was this triangle from Oostend to Dover to Calais. British tourists arrived with their 45s, and we listened to them together on the beach, learning how to play the songs on our guitars.”

A Frenchman working for Classic 21, Eric Laforge, also noticed the difference. “In France”, he says, “I could not host a show freely, I had precise songs to play and even lines to say on-air. One day, while driving through Wallonia, I heard Classic 21 and thought, this is what I want to do. Such a radio would not work in France, because rock culture is less strong there. A man like Neil Young is almost unknown in France, but he is a superstar in Belgium. Everyone here knows bands like Kinks or Canned Heat, in France it's a niche thing”.

Classic 21 is one of two pillars that allow classic rock music to stay alive and well in Belgium – the other being the Spirit of 66, a big American-like bar converted into a small concert hall in Verviers. Any classic rock artist passing through Belgium will be promoted on Classic 21 and invited to play at the Spirit of 66. The venue’s owner, Francis Giron, explains “I noticed that bands went on tour in Europe through the Low Countries and then to Germany, and I thought, we're right on their road, they could play an extra date here. Now I have to refuse bands because I could have three of them every day”. His bar became a cult place where rock legends could be seen playing at an arm's length from the audience.

Every witness reports that this love affair with rock music is due to an early openness to a form of art that was primarily expressed in a foreign language, something that was not a given elsewhere on the continent. Belgian cartoonist François Jannin reported a similar story about how his French colleague, cartoonist Gotlib, had to come to visit him in Brussels to discover the Monty Pythons “because English humour was banned in France at the time”.

So here is a tribute to Belgium's role in bringing rock music out of its Anglo-Saxon shell. Next time you hear “Born to be wild”, remember it can be played on a Walloon highway too…

By Julien Oeuillet