A bubbling crowd of 3,000 pupils in what looked more like the campus of an American elite university than an ordinary Brussels school. This is what I discovered last month as I entered the European School of Brussels IV to take part in its annual Philosophy Days.

It was not the first time I had visited the site. I had already done so twenty years ago, when it was in the process of being vacated by a Belgian military school known as the Ecole des Cadets. I was then desperately trying to find additional arguments in favour of choosing this site, in the northern Brussels neighbourhood of Laeken, for the fourth large European School. This was essential, I believed, to prevent Belgium’s federal government from making a major blunder, with catastrophic consequences for the harmonious development of Brussels. Here is the context.

In the early 2000s, discontent ran high among the Brussels-based EU staff. The three existing European Schools were overfull, and parents feared that soon many of them would find no place for their children in a school they regarded as suitable. Whose fault was it? EU member states and the European Commission were responsible for funding the functioning of the European schools, but it was the Belgian federal government that was expected to provide adequate premises at its own expense.

The Régie des bâtiments, the organ managing the Belgian state’s real estate portfolio, had come up with a list of seven possible sites. Lobbies were pulling in all directions. Some members of the party of the federal minister in charge of the dossier, Didier Reynders (now European Commissioner for Justice), were even arguing in favour of a site in Wavre, 30 km south-east of Brussels. At the same time, none of the municipalities with sites on the list showed the slightest enthusiasm for welcoming the daily procession of school buses delivering European School pupils in the morning and picking them up in the afternoon.

However, something of far greater importance than the profits of rural landowners or the tranquility of urban neighbourhoods was involved in the choice of the site. The data available at the time showed a heavy concentration of ‘Europeans’ — defined as citizens of the (then) 15 EU member states minus Belgium — in the south-east of the Brussels-Capital Region. And data about population movements within Brussels showed what a geographer friend described as ‘the Eurocrats driving the Moroccans across the canal’.

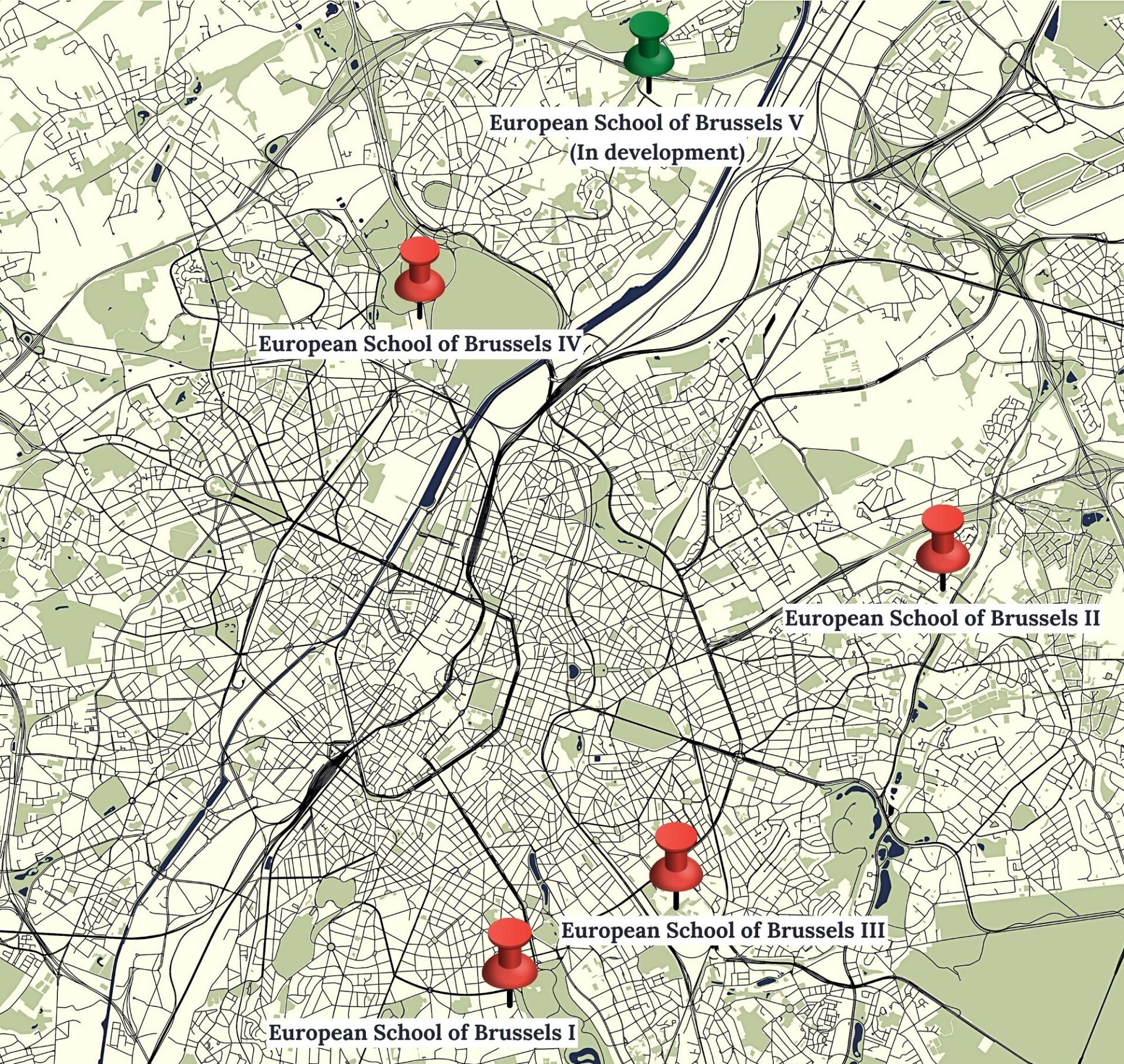

The installation of the European institutions and, later, of three large European Schools in the same south-east quadrant (in Uccle, Woluwé and Ixelles) was gradually leading to a dualization of Brussels, with a ‘European ghetto’ on the right side of the canal that crosses Brussels from the south-west to the north-east and an ‘immigrant ghetto’ on the left side.

What can public authorities do to halt or even reverse this sort of process? Not much. Choosing the location of a school is one of the few instruments at their disposal. The list of sites presented by the Régie des Bâtiments included only one on the left side of the canal that could be made available within a foreseeable future: the site of the Ecole des cadets in Laeken.

But it was widely believed that the European Commission, backed by parents at the existing European Schools, would never agree to a site located so far away from where families lived. As a result, various alternative plans were already being made for the Laeken site. In particular, the municipality of Brussels had taken an option on the site for its police headquarters.

Time was pressing, but something could still be done. In December 2002, an informal meeting gathered the presidents of the parents’ associations of the three European schools, the deputy head of the Régie des bâtiments and the Belgian ambassador responsible for liaising between the federal government and Brussels-based international organizations. The aim was to dispel European school parents’ illusions about finding a site that would meet their many desiderata, and at the same time make them more aware of the long-term impact on Brussels of the location of the new school.

Next, it was important to prevent the choice of the Laeken site being blocked by an irreversible commitment to another use. In June 2003, Philippe Close, now mayor of Brussels and then chief of cabinet of mayor Thielemans, confirmed that the option taken for the Brussels police could be lifted if the Laeken site was chosen for the school, and that it could be maintained until the site was officially chosen, thereby blocking other alternative plans.

The fourth European School of Brussels, in Laeken, today hosts some 3,000 students

The road was kept clear, but the parents’ associations had to give their consent. In September 2003, they held a joint general assembly in the auditorium of the Charlemagne Building. It was quite a challenge to convince parents that the new school should be located not where they currently lived, but rather where it was desirable that they (and above all their successors) should live.

Not all the arguments used against other sites on the Régie’s list were sound, but the assembly was cleverly managed by the parents’ association presidents. The conclusion of the meeting — to my great relief — was that the parents would not object to the Laeken site if it was still on offer.

This did not stop the lobbying for other sites, however. Above all, the European Commission kept arguing in favour of the Delta site, in the middle of the south-east quadrant. It was Neil Kinnock, the Commission vice-president, who needed to strike the final deal with Belgium’s federal prime minister Guy Verhofstadt, who - given the continuing deadlock - had taken the matter into his own hands. The decisive meeting was due to take place in the first half of April 2004.

On 5 April, a letter I co-signed with academic colleagues Eric Corijn (VUB), Chris Kesteloot (KU Leuven), Paul Magnette (ULB), Albert Martens (KU Leuven) and Marco Martiniello (ULiège) was sent to the Belgian government, restating the reasons for resisting the pressure from the Commission, so as ‘to prevent Brussels from becoming a caricature of a dual city’. Choosing the Delta site, the letter said, ‘would lead, gradually but irreversibly, to the constitution of the south-east quadrant of Brussels into a ’European ghetto’, in total contradiction with the ideals of mixed and balanced cities proclaimed at all levels. It is in no one’s interest to turn the capital of Europe into a city whose duality would shame the whole of Europe.’

The letter reached Verhofstadt’s chief of cabinet Peter Moors, who contacted us the next day to discuss its content, just before the decisive meeting. Verhofstadt stood firm and the Commission gave in. On 3 May 2004, in the absence of opposition from the Brussels parents’ associations, the Board of Governors of the European Schools officially approved the choice of the Laeken site, as did, on 20 July 2004, Belgium’s federal government. ‘De kogel is door de kerk’, wrote Peter Moors shortly afterwards — a strange Dutch way of saying that the matter was irreversibly settled.

Did the decision produce the intended effects? When in Laeken last month, I tried to find out by asking pupils attending the opening ceremony of the Philosophy Days whether they lived on the right or left side of the canal. This led to some confusion, as they seemed (excusably) puzzled about what counted as the left and right side of a canal. But the two pupils in charge of escorting me, Dora from Spain and Veronica from Romania, lived in Jette and Grimbergen respectively, definitely far to the left of the canal. Moreover, the decision has recently been taken to locate a 5th European school next to the military hospital in Never-Over-Heembeek; once again, and this time seemingly without much resistance, given the precedent, on the left side of the canal.

Mission accomplished? Not at all. This is only the beginning. The dissemination of the ‘European’ population throughout the Brussels Region is a precondition for what would really enable ‘European’ and other Brusselers to intermingle and would thereby terminate the current de facto apartheid.

‘We consider it unhealthy that the children of European civil servants are confined to fortress schools that are increasingly closed to the other children of Brussels. In order to stop this harmful development, it is important to initiate without delay an institutional and pedagogical reflection involving our Communities and the European authorities on the setting up of multilingual kindergartens and primary schools capable of accommodating a wide variety of 'local' pupils while satisfying the legitimate expectations of European civil servants.’

This is what we wrote in our letter of April 2004. A further concentration of the ‘European’ population in the south-east quadrant would have turned this ambition into sheer wishful thinking. Since 2014, there has been some more thinking about the possibility of ‘type II European schools’ (co-funded by local and European authorities) and even a little bit of potentially relevant action: in September 2022, a francophone school in the European quarter was allowed to launch an experimental ‘trilingual’ section (French-Dutch-English). But there is a long way to go, and no lack of obstacles ahead.