On this day, on 4 March 1848, Karl Marx was arrested and ordered to leave Belgium after three busy years residing in Brussels. It would be in this city that Marx wrote one of the most influential political pamphlets of all time – the Communist Manifesto.

“Belgium, a paradise for the rich, hell for the poor,” is how Karl Marx described the country where he spent three seminal years of his life between 1845 and 1848. After the German thinker was expelled from France in February 1845 for revolutionary activities, he travelled to Belgium, where he settled in Brussels. Marx achieved a Belgian residence permit after declaring that he was a philosopher.

After staying in three other locations across the city, Marx moved into 50 Rue Jean d'Ardenne in Ixelles – which at the time was called Rue d’Orlean. He stayed there from October 1846 until 19 February 1848 when he left Ixelles to settle in Place Sainte-Gudule – just south of the cathedral. He would only inform the police of his change of address on 26 February, a week before his arrest.

Marx's house in Ixelles.

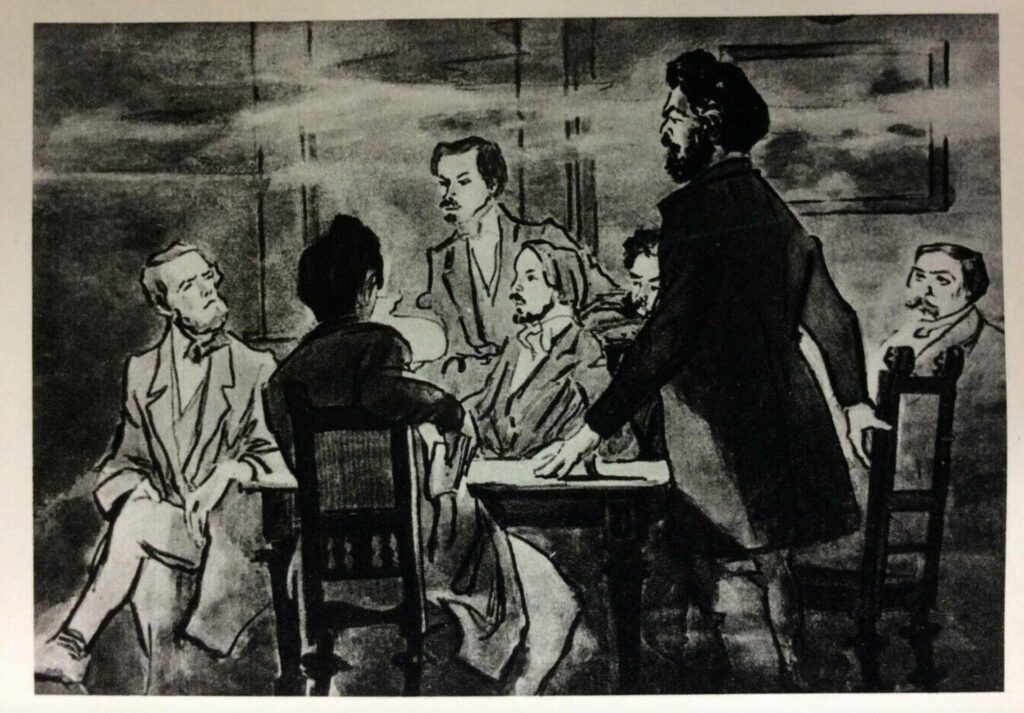

During his time in Brussels, Marx taught political economy, wrote for a German-language Brussels newspaper and gave numerous public speeches. He was a frequent visitor of Le Cygne in Grand Place – he even celebrated the New Year there in 1848.

But Marx also used the restaurant for his political work. While legend states that this was where he wrote the Communist Manifesto, accompanied by a glass of wine and cigars, Marx actually used the backroom of the premises to educate workers about their exploitation by the monarchy and ruling elite.

Marx would later be joined in Brussels by his close friend and co-thinker Friedrich Engels. It was here that the two would develop the philosophy of communism, and went on to become the intellectual leaders of the working-class movement.

Together, the two founded the Communist Correspondence Committee in 1846, which was then renamed the Communist League in 1847, to organise socialists from different countries to form a revolutionary proletarian party. With organisational chapters in London, Paris and Cologne, the two were commissioned to write a manifesto summarising the doctrines of the organisation during the Communist League's Second Congress in London at the end of 1847.

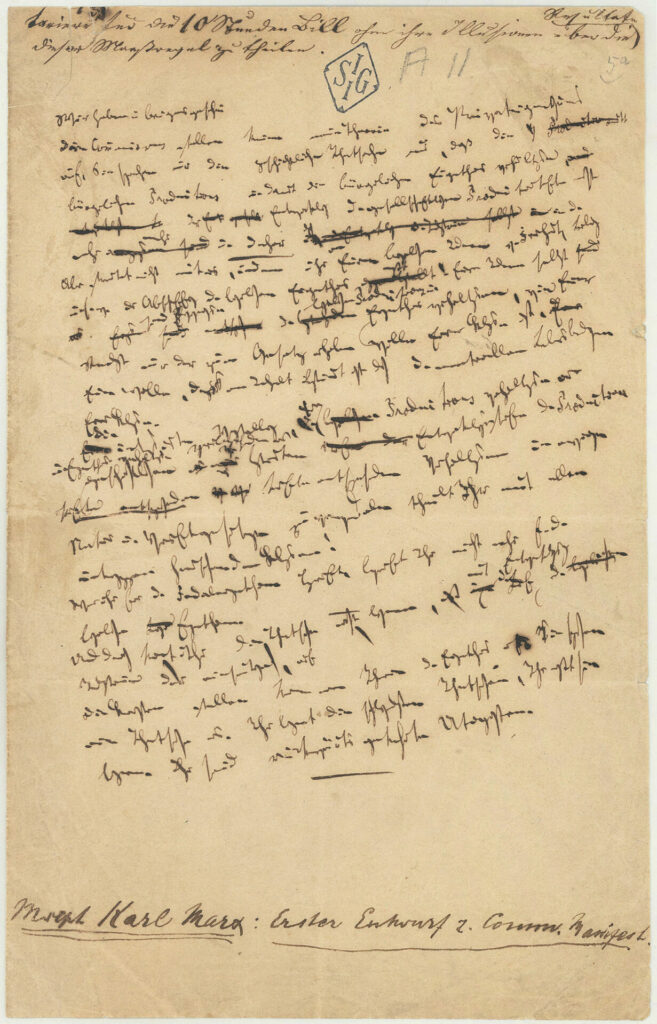

In January 1848, Marx returned to Brussels to write the 23-page Communist Manifesto pamphlet, based on a tract previously written by Engels. It was published in London in February. With the pamphlet still hot off the press, a revolution broke out in France, forcing King Louis-Phillipe to abdicate to make way for the establishment of the French Republic.

Only surviving page from the first draft of the Manifesto, handwritten by Karl Marx in Brussels.

Marx had also been the vice-president of a leading international pro-democracy movement in Europe – the Brussels Democratic Association – since November 1847. Following the revolution in France, the association came out in favour of the rapid arming of Belgian workers and the struggle for a democratic republic.

“On Sunday, 27 February the Brussels Democratic Association held its first public meeting since the news of the proclamation of the French Republic. It was known in advance that an immense crowd of workers, determined to lend their active help to all measures that the Association would judge it proper to undertake, would be present,” Marx wrote in La Réforme, around 10 March, 1848, following his Belgian exile.

Karl Marx portrait. Credit: Belga

With the fever of revolution gripping Europe, Belgian authorities watched his movements closely. The police closed in on Marx’s activities after they accused him of planning to use a large sum of money to buy weapons for a small group of revolutionaries. Authorities believed Marx was seeking to ignite a republican insurrection in Belgium, even if the money in question had, in fact, been an inheritance from his father.

At 01:00 on 4 March, Marx was arrested by the police as he was preparing his luggage to leave Brussels – the authorities had already ordered him to leave Belgium. Marx was detained for one night at the Amigo Prison, which today is a five-star hotel of the same name, just by the Grand Place.

Marx was then taken, under police escort, to the French border and onto Paris with his children and his wife, who had also been arrested and mistreated by the police.

After leaving Belgium, Marx wrote about his last turbulent days in Brussels and his vision for a Belgian republic: “The Belgian people are republicans. The only Leopoldists are the big bourgeoisie, the landed aristocracy, the Jesuits, the officials and the ex-Frenchmen who, chased out of France, now find themselves at the head of the Belgian administration and the press.”

Marx’s vision for a Belgian republic is not so well-known today, nor is his political work in Belgium. Yet, it would be at his Ixelles home in Brussels that he penned the famous words in his manifesto: “Workers of the world, unite.”

"Today in History" is a new historical series brought to you by The Brussels Times, aiming to take you on a trip down memory lane for newcomers and Belgians alike, written and compiled by Ugo Realfonzo & Maïthé Chini. With thanks to the Belga News Agency.