In the oldest city of Belgium, Tongeren, located about 80 km from Brussels, a mysterious warrior is proudly standing in the city square and closely watching the surroundings. Who is this figure and what does he mean for the Belgian people? Before we relate the story of this legendary figure, Ambiorix, his tribe the Eburones, their fate 2,000 years ago and legacy today, we have to travel even further back in time. We know their story mainly through the expansion of Rome and the rise to power of Julius Caesar, as described in his classical book on the wars he waged in what is now mainly France and Belgium.

Gallia in the sight of Rome

Rome had been expanding for centuries, crushing enemies in its way. In the second century BC, the process of conquering Gallia Cisalpina (Gallia on this side of the Alps, from the Roman point of view) was completed.

Rome did this to secure its own peninsula in the north, long after it had set foot in North Africa, Macedonia and Spain. The threat of the Gallic tribes was dealt with, for the time being. However, new Gallic tribes were pushed over the Alps by the movements of others in the north.

Gallia Transalpina (Gallia over the Alps) was established in 121 BC to secure the Roman routes to Hispania (Spain). Later it was renamed Gallia Narbonensis, after its newly established capital city. The Romans also called it Provincia Nostra (Our Province) for years, as their first province over the Alps. This name is still used in France today: Provence.

Caesar rises to power

Another contributing factor to the conquering of Gaul lies in the personal ambitions of Gaius Julius Caesar (100-44 BC). This story starts in 60 BC, when he and Marcus Bibulus were elected consuls – the highest executive office in the Roman Republic and held for one year. From 62 BC onwards, he also governed Hispania Ulterior as proconsul.

In 60 BC, he had already formed the First Triumvirate, an informal political bond solely based on a private agreement and kept secret during the first year. Caesar teamed up with two of the most powerful men of their time, Crassus (115-53 BC) and Pompeius (106-48 BC), to dominate the Roman Senate, through their networks of patronage.

The relationship between these two former consuls had been strained for decades, however Caesar finally reconciled them. From now on, “nothing would happen in the state, without the approval of the three.”

Caesar knew that after a term as consul, his military powers would end. He must have realized that to stay in the picture for a next term as consul, he needed armies at his command and glorious military victories, which would result in triumphs for Rome. In 58 BC, he became governor (proconsul) in Gallia Cisalpina, Illyricum and Gallia Narbonensis for five years. This allowed him to command four legions from the start, but only for the defence of these territories.

| How reliable is Caesar on the wars in Gallia? Caesar’s arrival in Gallia meant war, as other Gallic peoples were already on the move and “threatening the Roman peace,” pushed forward by others and/or attracted by Roman wealth. The main written account on the following wars in Gallia are the Commentarii de Bello Gallico (Comments on the Gallic Wars), written by Caesar himself or his scribe, based on military reports. The work is divided into eight books, one per year, of which the last one was written by Aulus Hirtius after Caesar’s death. It has been said that Caesar made his final notes of the first seven books in 52-51 BC during his winter camp. It is also believed that they were presented each year to the Roman Senate. Note that Caesar does not use the word historia (history) in his title but rather “comments.” This raises some historical concerns. Caesar’s comments are the main surviving source about his own acts. Unfortunately, accounts by contemporary historians were mostly lost. Caesar used his “comments” to present “his” narrative to the Senate. From that point of view, most of his personal motives or ambitions were missing. In his comments, Caesar focused on his military actions. He is always depicting himself (in third person) as the merciful and patient leader, however ruthless when necessary. Some proceedings are described in detail, while others remain deliberately vague when needed. Military actions are never the fault of Rome but instigated by “others”. He never provoked them - they provoked Rome. Note that Caesar was not given a mandate by the Roman Senate to conquer more lands. In his writings, he always answered or anticipated threats. Through the reporting, he ensured the necessary logistics for the following year. It is possible that he is giving “history a hand”. However, blatant lies would be discovered, since literate officers sent letters to the elite and Roman Senate as well. The Gallic tribes were always described as “great adversaries”. When he defeated them, it added to his glory. The oldest surviving copy of Caesar dates from the 9th century. That’s almost one thousand years of textual history we know very little about. |

The Belgae in the sight of Rome

When referring to Belgica, roughly the territory of nowadays Belgium, the tribe Eburones, and their leader Ambiorix, we have to turn to Caesars account, although it may not be completely reliable. It has to be read with a critical mind. During the first year of Caesar’s campaigns in 58 BC, he had already conquered a large part of Gallia.

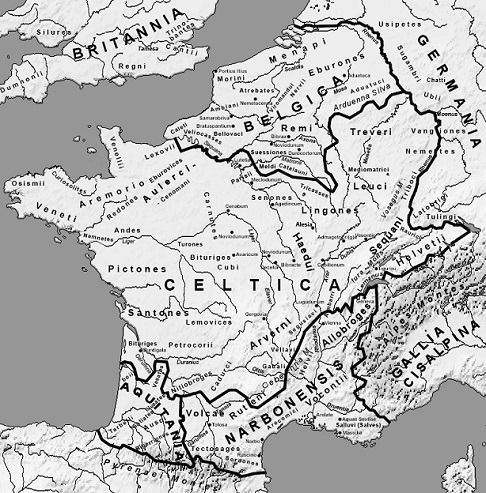

Map depicting the tribes in the region during Julius Caesar’s times.

Conflict had started when the tribe Helvetii requested peaceful passage. This wasn’t granted and their defeat resulted in the clearance of the Rhône and Saône valleys, creating an easier path to Belgica. The next year, his armies advanced their actions up north, where the tribes of the Belgae lived.

Note that Belgae or Belgica are Caesar’s terms. The territory was never united before. The Belgae consisted of dozens of tribes and peoples. We don’t know whether the tribes referred to themselves by this name. However, the name had its roots in Proto-Germanic and refers to “swelling (with anger)”. The word also survives in Dutch today, verbolgen, meaning “being very angry”. The tribes of the Belgae would remind Caesar of this meaning later on.

First coalition of the Belgae: 57 BC

This first of two larger military operations in Belgica had not left any archaeological traces – or they have not been found yet. In 57 BC, Caesar mentioned the Eburones and Ambiorix for the first time. The Remi in the south of Belgica were allied with the Romans and gave details about the tribes to the north of them.

The group of tribes that Caesar called the Belgae were living in-between the Gallic tribes and the tribes across the Rhine, the Germanii. Their origins or culture were not always clear, actually not even for Caesar. From the dozen tribes that assembled, he was told that five of them originated from over the Rhine, including the Eburones. However, if we look at their names, they were clearly Gallic. Ambiorix means rich king, and the Eburones are the people of the yew-tree (taxus).

Caesar anticipated the war and sent his armies into their territories. This resulted in the so-called “Battle of the Sabis.” Here, the Nervii, Viromandui and Atrebates tribes were defeated and the oppidum (stronghold) of Atuatuci was captured. The place was also called Atuatuca (possibly meaning fortress).

The people in Atuatuca were sold into slavery, as reported by Caesar. Afterwards, he learned from his merchants that there were 53,000 of them. During the battle itself, the Eburones were not specifically mentioned… but we will hear from them again.

Second coalition of the Belgae: 54 BC

The event that gave the Eburones a place in world history took place in 54 BC. In Book V, Chapter 24, Caesar tells us the story of a second coalition of the Belgae, under the leadership of Ambiorix, one of two kings of the Eburones. The other king was Cativolcus. According to Caesar, the Eburones lived mainly between the rivers Meuse and Rhine. Later authors added that the natural border between the Nervii and the Eburones was the river Dyle.

Because the corn had not flourished that year, due to a drought, Caesar decided to distribute his legions across several places to set up winter-quarters. The commanders of the army that was sent into Belgica were Sabinus and Cotta. About fifteen days after assembling their winter-quarters, a disaster was about to befall the Romans.

The two Eburones leaders had met with Sabinus and Cotta at the borders of their kingdom and had supplied corn to the Roman winter-quarters. Then the Eburones suddenly attacked Romans gathering wood, after which a larger group attacked the Roman camp. The attack was successfully stopped and the Eburones withdrew.

The Eburones asked for a meeting and Roman delegates were sent to Ambiorix. But the Romans were deceived. Ambiorix told the Romans that the other tribes, including the feared Germanii, were going to attack them. This resulted in the Romans preparing to leave their winter camp. When they did, the Eburones ambushed them from all sides. Ambiorix’s attack left about 6,000 Romans dead and their winter camp destroyed.

The news of his success spread among the tribes of the Belgae and boosted their confidence. Immediately, Ambiorix personally contacted the Nervii and the Atuatuci. That first tribe informed and mobilized five other tribes. This resulted in an attack on the winter camp of the Romans by the Nervii. It is believed that this camp was situated close to modern day Brussels, probably at Asse.

Caesar had written that the Nervii not only had been defeated but been “destroyed” in the previous war in 57 BC – and here they were back in full force. He is obviously not careful with the facts and it also supports the theory that the book was published in parts with little or no final editing.

A messenger with a hidden message was able to reach Caesar in Amiens, who sent reinforcements to defend the camp. Then he turned to the tribes of the coalition, defeated them all and surrounded the Eburones. Tribes from across the Rhine were invited to join and plunder. The uprising of the Belgae was defeated in about a year.

According to Caesar (Book VI), Ambiorix was seen fleeing in the night into the forests, protected by four horsemen.

| The fate of the Eburones Driven off from all parts; the corn not only was being consumed by so great numbers of cattle and men, but also had fallen to the earth, owing to the time of the year and the storms; so that if any had concealed themselves for the present, still, it appeared likely that they must perish through want of all things, when the army should be drawn off. And frequently it came to that point, as so large a body of cavalry had been sent abroad in all directions, that the prisoners declared Ambiorix had just then been seen by them in flight, […] but he rescued himself by [means of] lurking-places and forests, and, concealed by the night made for other districts and quarters, with no greater guard than that of four horsemen, to whom along he ventured to confide his life. Source: Comments on the Gallic Wars, book VI, by Julius Caesar Book |

The Belgae and archaeology

The original Roman name of Tongeren is Atuatuca Tungrorum, referring to the tribe that was invited to live in the lands of the Eburones after their defeat and dispersion. This led to confusion for many years. Was this the Atuatuca of the Atuatuci tribe? Or does it refer to the fortification of the Eburones, which Caesar also called Atuatuca?

Archaeologists have not uncovered any trace of inhabitants in Tongeren before 15 BC, when Roman settlers founded the city. However, in 2002 in Heers (close to Tongeren), a large coin deposit was found. Of the 158 gold and silver coins, 116 were thought to be related to the Eburones. Together with the other coins, they matched the coalition that Ambiorix had set afoot. They were freshly minted and by the same stamp.

The coins were without any text and they all looked alike. They showed an ancient or Celtic symbol consisting of a triple spiral (triskeles) on one side and a stylized horse on the other side. The horse is called "Macedonian" after King Philip II of Macedonia who was the first to mint coins with a picture of a horse.

Coins were mostly used to pay warriors, not for trade. In 2008, in Amby (Maastricht) in the Netherlands – also close to Tongeren – other coins thought to be related to the Eburones were found. To this day, they are believed to be the most definitive proof of their presence.

Coins minted by the Eburones. The coins were mostly used to pay warriors. They showed an ancient or Celtic symbol consisting of a triple spiral (triskeles) on one side and a stylized horse on the other side. To this day, they are believed to be the most definitive proof of the Eburones presence. Photo Credit: Gallo-Romeins Museum

The battlegrounds, burned houses, fortifications and corpses did not leave any traces or are yet to be found. If Caesar wanted to wipe out the Eburones from the face of the earth, he mostly succeeded. When Caesar wrote that a tribe was completely destroyed, a major part of its members may have been sold as slaves. By not reporting it, he evaded taxes.

Traces of mass massacres have not yet been uncovered in Belgium. Another military action, described by Caesar, did leave traces in the Netherlands. His war against the Tencteri and Usipetes in what is now the Netherlands, would today be described as war crimes or genocide. The remains of more than one hundred individuals, including women and children, have been found.

The name of the Eburones disappeared from history. Ambiorix was believed to have successfully fled, never to be grasped by the Roman Eagle. Part of his people may have been dispelled or taken shelter with other tribes. The unknown fate of Ambiorix must have fed his almost mythical status.

Ambiorix and modern-day Belgium

The legendary Ambiorix survived in a way. With the birth of the Kingdom of Belgium in 1830, the new nation looked at its past and raised statues in honour of its legendary heroes. Among the best known internationally were Charlemagne in Liège (1842) and Godfrey of Bouillon in Brussels (1843).

In 1866, the statue of Ambiorix was added to this impressive lineup of “national figures” in the main cities. The statue was erected in the city square of Tongeren, long believed or supposed to be built on the very site of the former stronghold of the Eburones.

Statue in Tongeren in Belgium, depicting Ambiorix, one of two kings of the Eburones.

This statue was also the result of 19th century romantic sentiments and values. His figure played an important role in the education of the new nation. Ambiorix had stood up against great powers, against Caesar himself. And most importantly, he united the other Belgae “for their independence”. What could make him more admired by Belgian nationalists?

In the textbooks of Belgian elementary and even high schools, the tribes of the Belgae became “Belgians”, or the “Old Belgians,” connecting the new state of Belgium to the tribes of the past. This led to the popular misquoting of Caesar that “the Belgians are the bravest of all the Gauls”.

He is telling us about the Belgae, which he indeed considered the bravest or strongest, but this was because they were the furthest from the Roman Province, with their luxuries that softened the mind, and because there were close to the warmongering Germanii.

The memory of the Belgae was used to teach Belgian students about loyalty, dedication, hospitality, equality, respect for nature, devoutness and above all unity among the peoples of the Belgae leading up to the state of Belgium. Caesars Commentarii were read by generations of students of Latin, as it still is, without much source criticism. That way they still feed the romantic views of these tribes.

In 1954, indeed 2000 years after the uprising by Ambiorix, a museum was opened in Tongeren, named the Gallo-Roman Museum. The museum was conceived as a walk through time, from the first inhabitants in the region and their different cultures, up to the Roman period.

In 2011, it received the European Museum Award. In 2012, the museum, together with attached universities, started to exhibit the findings of eight less-documented coin deposits and the discovery of the oppidum (stronghold) of the Atuatuci in Thuin (Henegouwen).

Bart Demarsin, exhibition coordinator at the museum, tells The Brussels Times that although the names of the tribes are never mentioned on the coins, “we are quite sure, based on the date and place, that the coins found in Heers and Maastricht belonged to the Eburones.”

In 2005, the media of the Dutch-speaking part of Belgium chose their “Grootste Belg” (“Greatest Belgian”) while the French-speaking media named the “Plus grand Belge.” In the northern part of the country, Ambiorix came in 4th place, in the southern part he was only awarded 50th place.

The legacy of Ambiorix apparently lives on, although maybe a bit stronger in the parts of Belgium where he supposedly lived and centuries later was honoured with his own statue and museum.

By Tom Vanderstappen