Membership of the European Union is meant to blur national borders, yet it also seems to stimulate the desire to create new ones. While Britain is struggling with Brexit, many in Scotland would like to leave the United Kingdom and remain in the EU. Catalonia is seeking to split from Spain. And in Belgium, Dutch-speaking Flanders and Francophone Wallonia have long been tempted to go their separate ways – potentially leaving Brussels as an independent city state.

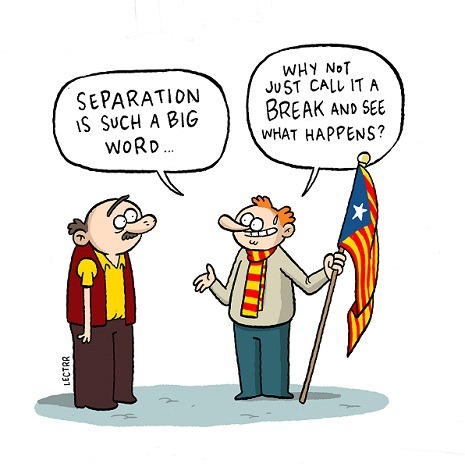

This is not a manifesto for separatism. There are generally all sorts of positive reasons – historical, cultural, political and economic – why a country may wish to stick together, the most important one being that most of its citizens want it to. When some regions have particularly strong identities, diverging interests and a fractious relationship with the rest of the country, giving them plenty of autonomy is often the best solution. Divorce tends to be costly, painful and bitter.

At the same time, self-determination isn’t always a bad idea. How else did most countries in Europe come about? Belgium itself was once part of the Netherlands (and before that Austria and Spain). You don’t have to be a nationalist extremist to think that if a clear majority of people in a region feel different and want to leave, breaking away is sometimes the right move. Nobody argues that the seven independent states that were until recently part of Yugoslavia – Slovenia, Croatia, Serbia, Montenegro, Bosnia, Kosovo and Macedonia – should be combined again. And if the prospective new country – be it Catalonia, Flanders or Brussels – wants to remain in the EU, the costs of splitting up would appear to be minimised.

Historically, there were powerful reasons for smaller European countries to form bigger ones, as in 1871 when both Germany and Italy were unified. Larger states enjoy bigger domestic markets, offering economies of scale for companies and the potential for more growth-enhancing competition. Bigger powers can also boss smaller ones around. And more populous states can muster bigger and better-equipped armies.

But markets, muscle and military might are no longer constraints on the size of states in the EU. Within the EU’s single market, the size of the domestic market no longer matters: a company in Brussels or Barcelona can sell freely to 510 million Europeans. Moreover, by clubbing together in the EU, even small European states have global clout, not least when the EU negotiates free-trade agreements with the rest of the world on their behalf. And with war among EU members now (almost) unthinkable – and Europe as a whole protected (for now) by an American nuclear umbrella – being small is no longer a security issue either.

Surely size still matters in other ways, though? When a region wants to break away, opponents tend to argue that the new country would be too small to be viable. But if you look at a map of Europe, you need to squint to spot the smallest countries. At the microscopic end, Vatican City is only 50% larger than the Parc du Cinquentenaire (Jubelpark). If you focus only on the 28 EU member states, the tiniest, Malta, is only a 2,000th of the size of the biggest, France. So in practice, it seems like there is scarcely a lower limit on the size of a country.

Looking at population size leads to a similar conclusion. There are apartment blocks that house more people than the Vatican, which officially has a population of 451. Within the EU, the Mediterranean island of Malta has a population of only 420,000 – around a third that of the Brussels Capital region. That makes the notion of Brussels as an independent city state seem less absurd.

For sure, bigger states still have more clout. Germany, the EU’s biggest and most populous economy, tends to get its way in the eurozone; the likes of Estonia (population: 1.3 million) mostly have to toe the line.

But smaller states enjoy outsized influence within the EU. They have a disproportional representation in the European Parliament: Malta has one representative per 70,000 people, Germany one per 860,000.

On the Governing Council of the European Central Bank (ECB), which sets interest rates for the entire eurozone, each national central bank has one representative, so Cyprus weighs as heavily as Spain. Including the six members of the Executive Board tiny Luxembourg has 2 of the 25 seats on the Council, while Spain has only one.

In the European Commission, Luxembourg has one Commissioner just as Germany does – the president, Jean-Claude Juncker, no less. Remarkably, four of the 12 presidents of the Commission have come from the Grand-Duchy.

Were Luxembourg part of neighbouring Belgium, France or Germany, its half-million people would scarcely enjoy as much influence in the EU. On that basis, it is hardly irrational for many in Catalonia, whose population is thirteen times that of Luxembourg, to want it to be a member of the EU in its own right.

It’s not surprising that EU membership encourages separatism. But there’s a catch. While the EU is kind to existing small states, it is much less welcoming to prospective ones. Catalan separatists insist that Catalonia would remain in the EU and the eurozone if it gained independence – and there is no technical reason why it shouldn’t – but politically that is extremely unlikely.

The official EU line is that an independent Catalonia would need to reapply to join the EU – a move that Spain would surely veto. While it would still be able to use the euro, it would do so as a non-member, like Montenegro, whose banks don’t have access to liquidity from the ECB and whose government has no recourse to emergency loans in a crisis. No wonder banks headquartered in Barcelona are now planning to relocate to Madrid.

Yet undermining the rationale for nation-states to stick together while at the same time setting in stone their boundaries is a recipe for political instability and discontent. Ultimately, it could make independence-minded Catalans who currently love the EU (and their sympathisers in Flanders and elsewhere) resent it.

Since Britain is exiting, the EU would presumably be more welcoming to an independent Scotland. The EU might also be more accommodating if a country agreed a velvet divorce, as when Czechoslovakia, long before joining the EU, split into the Czech Republic and Slovakia by mutual consent. If Belgium ever decided to dissolve itself, all its constituent parts would probably have a right to remain in the EU and the eurozone.

At a deeper level, there is a tension at the heart of the EU between the claim that it is a union of citizens and the reality that it is primarily a union of member states.

By Philippe Legrain