Forbidden love across religions. A Christian converting to Judaism. A village pogrom during the First Crusade. A desperate mother searching for her lost children. The eternal refugee looking for a safe place. These are the tantalizing threads that Belgian novelist Stefan Hertmans weaves into his historical fiction, The Convert.

An international bestseller, it is a love story between a Christian girl and a Jewish boy set in medieval France. But for Ghent-born Hertmans, one of Belgium’s most celebrated living authors, the medieval Romeo and Juliet aspect was made even more compelling by the real-life inspiration for the tale. The result was the product of extensive research and creative imagination. “Writing the book, I felt that I was living intimately with the girl,” Hertmans says. “At some point, I was so overwhelmed by her emotions that I really suffered with her.”

The Convert takes place mainly in France in the years before the outbreak of the first Crusade in 1096. Vigdis Adelaïs Gudbrandr, born in Rouen in 1070, was the daughter of an aristocratic mother and a Norman knight. She was just 17 when she ran away with David Todros, a rabbi’s son and visiting student from Narbonne.

It seemed an impossible story. Marrying across religions was forbidden at the time under Christian dogma. Indeed, Jews were barely tolerated in the community. If caught, both risked their lives, she for heresy and he for breaking the law of the church and the country (although not Jewish law, which welcomed proselytes).

But she would elope, marry David, convert to Judaism and take the name Sarah Hamoutal Todros. Then she would journey with her husband to Moniou, a village in Provence, where the first of her four children was born. However, tragedy would strike when soldiers of the First Crusade attacked the village and burned the synagogue. Her husband would be killed and two of her children taken away.

Bestseller and opera

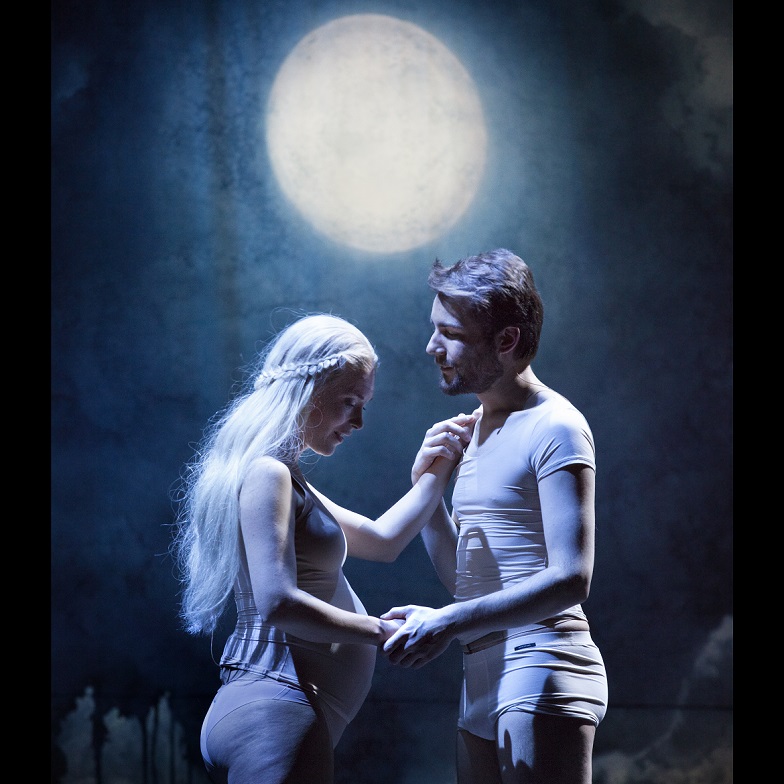

The Covert was first published in Dutch in 2016 under the title De Bekeerlinge and translated into English in 2019. Last year, the book was turned into an opera directed by Hans Op De Beeck, with music by the composer Wim Henderickx, who sadly passed away in December. The opera was performed in Ghent and Antwerp in May and June last year and will be performed again this May in Rouen, a city which features in the story.

Scene from last year’s opera of The Convert

In his home in Dworp, a quiet Flemish village south of Brussels and close to the Hallerbos, 71-year-old Hertmans explains how he stumbled onto the story, and how he turned it into a piece of historical fiction. “I believe that at every place where you live and where you start to ‘dig’, you’ll find an interesting story which you can write about,” he says. With The Convert, he was inspired by both historical documents, and what he discovered in the village. But the digging came first.

Hertmans is in his study lined with bookshelves from floor to ceiling. Behind his curved desk in maple wood hangs a huge painting made by his grandfather: a copy of an old painting of St Martin Dividing his Cloak by the Flemish painter Anthony van Dyck.

He has built up a reputation as one of the finest writers in Dutch today, not just in novels, but essays, short stories and poetry. One of the first things he shows me is his grandfather’s notebooks, which inspired him to write his first bestselling 2013 novel War and Turpentine (Oorlog en Terpentijn). The novel, nominated for the Man Booker International Prize, is about his grandfather, the artist Urbain Martien during the First World War. "This is the first of my trilogy of books inspired by local information," Hertmans says. The Convert is his second.

Stefan Hertmans in his study, credit: The Brussels Times

Hertmans is not done with historical fiction. The third book in his trilogy inspired by local stories is The Ascent (De opgang), published in 2019. The book is set during the Second World War and inspired by a house in Ghent, which he bought impulsively in 1979. “I was taken aback to discover that the previous owner of the house, Willem Verhulst, had been a Nazi collaborator,” he says. Twenty years later, when he read the memoirs of Verhulst’s son, he became fascinated by the life of this man on the wrong side of history and set out to write a book about him.

Holiday home mystery

But we’re here to talk about The Convert. Hertmans’s connection to the story is through his summer house in Moniou, now known as Monieux. He stumbled across the partly abandoned village in 1994 while travelling in Provence with his wife, looking for a house. They settled in Monieux and bought an old two-floor stone house with a winding path at the rear leading to the top of the cliff with a nearby chapel and the ruins of a medieval watchtower.

He was fascinated that the ruins were just 200 metres from his house, outside the village centre but still inside the defence walls that surrounded it. He heard rumours about a hidden Jewish treasure and a Jewish cemetery in the village. His neighbour, Andy Cosyn, who had written a book about the treasure, showed him the steps in a water hole. Hertmans identified it as the remnant of a Jewish ritual bath or mikvah. Back then, it was probably inside an annexe to the local synagogue.

“That’s how I started roaming around in the village ruins looking for traces of its Jewish past,” he says. “The Jewish quarter was located further away from the steps leading up to the tower so in times of danger they would hardly make it to the tower to seek refuge there.”

Later, another neighbour sent him a research paper simply entitled ‘Monieux’. It was published in 1969 by Norman Golb, an American historian and multilingual scholar known for his books on the conversion of European Christians to Judaism in the 11th century, the persecution of Jews at the time of the First Crusade, and the history of the Jews in Rouen in northern France. Golb, who passed away in 2021 at the age of 92, would become a key source for the historical background description in the book.

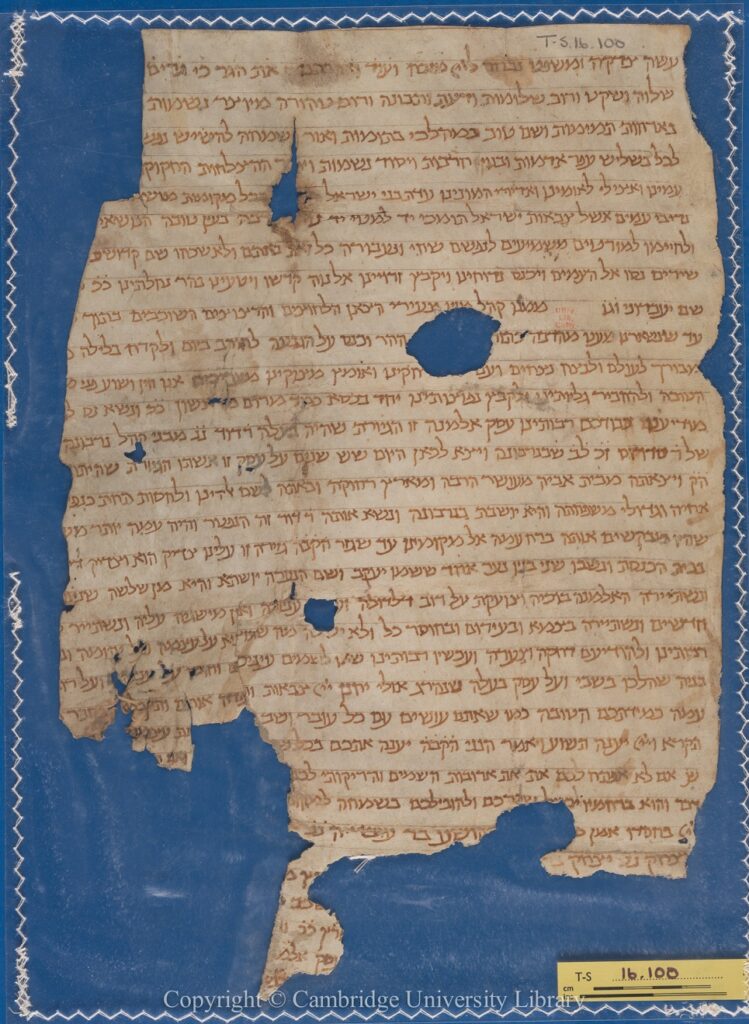

Golb was by no means the only source. Hertmans shows me his four-page bibliography and says it took four years to complete. Over the years, he corresponded with Golb and his son Raphael, who had translated documents found in the Cairo Genizah. This was a huge trove of hundreds of thousands of discarded Tora scrolls, sacred scriptures and correspondence, stored in the Ben Ezra synagogue in Fustat or Old Cairo, during the Fatimid rule. Only found in 1864, today they can be studied in university libraries and online.

The mysterious document in Hebrew that sparked Hertmans’s quest, credit: Syndicate Cambridge University Library

One salient document is a faded and torn letter Hamoutal carried with her from France. A page of 11th century parchment, it is now kept in the university library at Cambridge. The document relates, “the matter of this widow the convert, whose husband was the worthy David, may his soul rest in peace, who was a member of the family of rabbi Todros in Narbonne.” It continues to explain their story until the raid, when, “the husband was killed in the synagogue and two of her children were taken captive – a boy named Yaacov and a girl name Justa, she being three years old, and all they owned was plundered.”

Moniou, Monieux or Muno

The very existence of a Jewish community in the village is still doubted by some scholars. Other scholars argue that Monieux has been mixed up with Muno close to Najera in northern Spain. Both places are written with the same letters in Hebrew. Hertmans also wondered about it. “You could question on linguistic grounds that Monieux is the place where the young couple lived after they got married, and where the woman gave birth to their two children as described in the documents,” he says.

But having lived in the village for years, studied its history and made community connections, he felt confident it was the one. “You need to be close to the place and live here in Monieux to understand it,” Hertmans says. The search was complicated by the fact that the village’s mediaeval archives had been taken to nearby Carpentras centuries earlier where they were destroyed in a fire (Carpentras had a documented Jewish presence in the Middle Ages and still has a synagogue).

But does it matter if the village was Monieux or Muno? The book is a fictional love story. The girl converts to Judaism and is called Hamoutal by David (‘Warm Dew’ in Hebrew), a Biblical name which might have been common at the time. The story expresses their thoughts, feelings and fears on their dangerous flight to a safe haven.

The book also describes the author’s own journey as he tries to follow in their footsteps in modern France. This journey is both a documentary and a construction, as we cannot know for sure which route the couple took from Rouen to Monieux, 900km away, or if they at all lived in these places. “Assessing all arguments for and against, I’m convinced that Monieux is the place and that French crusaders attacked the Jewish community there,” Hertmans says.

The book is thus, partly, an excavation, as Hertmans tries to piece the elements together to see if they match his thesis. “If you look at the geographical circumstances and the fact that even in southern Provence Hebrew was heavily influenced by Spanish, you can easily understand that the rabbi of Monieux had studied in Spanish-speaking Narbonne,” he says.

Moreover, the rabbi of Narbonne, who was relatively autonomous (and claimed his heritage from King David), would hardly have sent his proselyte daughter-in-law to Muno in the direction of Najera and Burgos in Spain. That was leading to the famous pilgrimage site Santiago de Compostela, which teemed with Christian soldiers.

“I don’t believe a word of the Muno theory,” Hertmans concludes. “It’s only based on a few linguistic arguments that easily can be contradicted. Assessing all arguments for and against, I’m convinced that Monieux is the place and that French crusaders attacked the Jewish community there. The document mentions the pogrom explicitly. If you draw a line from Toulouse, where the French crusaders under the command of Count Raymond IV started, straight to Montgenevre, where the army crossed the Italian border, it runs through Monieux.”

Knight, Vikings, Normans, Jews

There is no map showing the route in the English paperback translation of The Convert but in other translations or the hardcopy version, there is a map right after the cover page. It could have facilitated the reading for some readers, he admits - but on the other hand, why do you need a map in a novel? It would also have disclosed the end of the story. It’s a fictional story despite all the historical research invested in the book.

During his research, Hertmans explored Rouen, where street names still recall its Jewish past. An intact yeshiva – a traditional Jewish rabbinical school – with a Hebrew inscription on the porch has been found in a cellar under the current courthouse. In Rouen, there was a flourishing Jewish community, which co-existed in relative harmony with the Christian neighbours. Religious incitement would lead to its destruction by crusaders on their way to the Holy Land in 1096. But before that, a local Christian girl could easily have met a student from the yeshiva in the streets as described in the book.

Hertmans recounts how Hamoutal leaves her parents and her Christian faith at a time of rising antisemitism. Her parents would never accept her marriage to a Jew. She faced particular hostility from her father, who was himself descended from pagan Vikings who had settled in Normandy and became devout Christians. The father, a Norman knight, does everything in his power to catch her and bring her back.

While David puts his wife in great danger, Hamoutal is prepared to sacrifice her previous life. He teaches her Hebrew, including how to pray in Hebrew, and she is gradually introduced to Judaism (by contrast, conversions to Judaism today involve lengthy courses). During their flight, they make love and are married in practise according to Jewish custom. Hamoutal is welcomed and accepted by David’s family. She converts and the marriage is formalised.

But Hamoutal is still torn between Christianity and Judaism, and is unsure about the difference between them and what to believe in. When distressed, she often returns to the Christian prayers of her childhood when she used to call out to Jesus Christ, Virgin Mary and the saints, practices she was supposed to forget. But Judaism is not a missionary religion and does not try to convert other people by force. The model for conversion is the Biblical story of Ruth who makes the decision willingly and says: “Your people is my people and your God is my God.”

How can this struggle be articulated, though? “It gets complicated,” Hertmans says. “Christianity and Judaism are monotheistic religions, with Christianity based on or originating in the Old Testament of Judaism, but Christians also believe in the Trinity: The Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit. Did Hamoutal ask herself if there is one true God? Or did she feel that she must adhere to something because of all her suffering? I might have given her some of my own religious doubt.”

Today persons of different religions can get married and live happily without one of them having to convert to the other’s religion. Is there a trap in converting to the other’s religion and not knowing if the marriage will last forever or end in divorce? “There is no general rule and situations differ,” Hertmans replies. “I think that parents of different religions, with children who fall in love with each other as in my book, should be tolerant and accept them. It’s their decision and happiness. My book is above all a plea for religious tolerance.”

But why must Hamoutal suffer so much in the book? Hertmans says he had no choice. He could not end the story as he wanted to or as the reader might expect: he had to be true to the historical documents. “I didn’t even see the end coming in the book, although it’s logical if you see how lost she must have felt,” he says.

While the events in the book took place almost a millennium ago, there are still lessons for today. “The book can also be read as a book about the eternal refugee looking for a safe place, which is more relevant than ever today,” Hertmans concludes, referring to the migration crises with refugees and asylum seekers fleeing persecution in search of safety and happiness. “They took their chances, as fugitives always do, because there were no other choices.”

M. Apelblat

The Brussels Times