For decades, the 1960s headquarters of two Belgian banks sat on each side of the Royal Palace in Brussels and were visible from it. Each the creation of a superstar architect, one domestic, the other American, they were luxuriously appointed inside and out, with modernist facades at odds with the more traditional style and scale of their neighbours.

By 2021, one of them was demolished, much of its structure literally ground to dust. The other meanwhile had been declared a protected landmark and flag-carrier of a generation of post-Second World War heritage which will be selected to join the mansions of the Grand Place and the Art Nouveau townhouses of Victor Horta in projecting the city’s image as a living outdoor museum to excellence in design.

The first formal protections for the built heritage of Brussels date from the 1930s with medieval structures such as the Hôtel de Ville and cathedral, beginning a trickle that would accelerate as the effects of postwar modernisation on the cityscape made itself felt in the 1960s. The current list of notable buildings in the region has its origin in 1975, when a 60-70-year-old house was likely to be in red brick, perhaps with a turret or decorated with vanished techniques such as plants depicted in stained glass or sgrafittes.

In the 2020s and beyond, centenarian architecture is as likely to have a flat roof and abstract decoration, if any at all, pointing the way to the modernist reimagining of the city’s homes and offices in glass, concrete and stone from the 1950s. Largely unloved, these are the 60-70-year-old buildings of today. Planners are beginning to look at them with the same concern felt by researchers from the Sint-Lukasarchief architectural archive when they began to compile a so-called ‘emergency’ catalogue in the 1970s.

Fighting for postwar architecture

In May 2022, the Brussels government invited the public to nominate their favourite modern buildings for inclusion on the list of protected buildings in the region. The 'thematic inventory of contemporary architectural heritage' is being steered by academics from the ULB but anyone can propose entries for their consideration, using an online form.

Protection of pre-1914 buildings has allowed Brussels to seize the title of "World capital of Art Nouveau," according to State Secretary for Urbanism and Heritage Pascal Smet. "Now I want to repeat that tour de force for our postwar heritage," he said.

Smet recognised that “many modernist buildings are not to everyone’s taste right now” and promised a targeted approach to select worthy choices for protection and renovation. “That way, we avoid repeating the errors of the past,” such as the destruction of major Art Nouveau works by Victor Horta as they approached their half-century, he said: “The Maison du Peuple is perhaps the most notorious example.”

Smet announced the launch of the Brussels region’s new modern-heritage strategy at the headquarters of the ING Belgium bank on Avenue Marnix, commenting that the choice of location was “no accident”. The modernist building with its prefabricated concrete facade, begun in the 1960s to the design of superstar architect Gordon Bunshaft of US firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM) had been awarded the status of protected monument the previous year.

For the authors of the often-scathing 2009 guide to modern architecture in Brussels (Archives d'Architecture Moderne: Bruxelles Architectures de 1950 à aujourd'hui), published with the support of the region, the four-square solidity of its 10-storey facade "makes it resemble a Venetian palace." Indeed, the bank sits opposite the ceremonial residence of the Belgian monarchy, its historic clients. As Bunshaft himself reportedly said of his creation: "When you are given an opportunity to do a building in Brussels on a site near the king's palace, if you don't do a monument, you are a jackass."

The forgotten superstars of yesterday

As Smet spoke, on the other side of the park, a brand-new bank building was nearing completion, hidden away behind an entirely fake row of neoclassical houses on the rue Royale. The design for the new headquarters of BNP Paribas Fortis (BNPPF) on Rue Montagne du Parc, with most of its façade on Rue Ravenstein next to Victor Horta’s Bozar, was greenlit in 2014 and its predecessor was demolished.

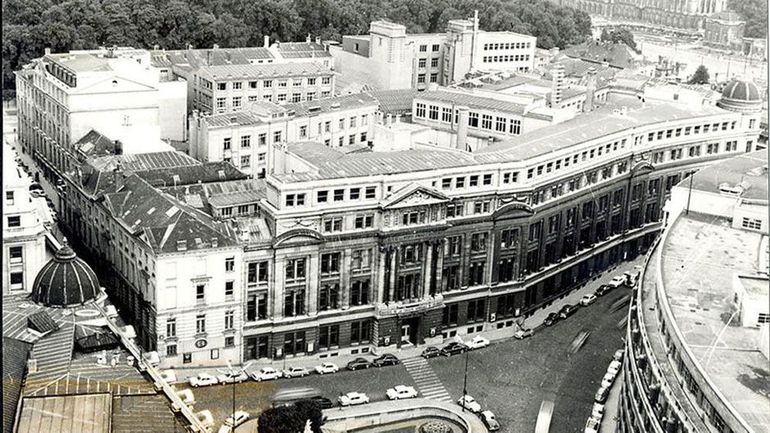

BNP Parisbas Fortis, before demolition in 2014

The previous building had been designed in the 1960s by another superstar architect (at least in that period), this time Belgian: Hugo Van Kuyck. Like his contemporary Bunshaft, Van Kuyck made his name in the 1950s with a dramatic commercial block constructed using the curtain-wall technique (non-load-bearing walls). For Bunshaft it was Lever House in New York City, for Van Kuyck it was the Prévoyance Sociale (now P&V), the first tall modern offices in Brussels, which still tower above the former botanic gardens.

The Antwerper’s landmark buildings in his native city, such as the Luchtbal social housing blocks and the Bell Telephone tower, survive and are listed by the Flemish region. As an intern of Victor Horta, Van Kuyck worked on the acoustics for the Henry le Boeuf concert hall in the Bozar. A decade later, as a Lieutenant-Colonel in the US army, his engineering skills helped with the planning of the 1944 Normandy landings. By 1960 he was successful enough to design one of the largest steel private yachts built in Belgium: sold to Jacques Brel in 1974, Askoy II is itself listed as marine heritage by the Flemish government.

But Van Kuyck’s dramatic design for the future BNPPF, then known as the Société Générale de Banque, in Brussels never won enough admirers. Unlike its earlier, more compromising, modernist and Art Deco neighbours in white and blue stone, the ziggurat-like, rectangular base in the obligatory beige of the period, ignored the curvaceous streetline of Rue Ravenstein. Its twin towers and black, curtain-walled boxes were visible from the nearby park and partly obscured the view from the Royal Palace towards the cathedral. By these criteria alone, its successor is far more discreet.

Rooted in history

The inauguration of the new BNPPF HQ in 2022 coincided with the bicentenary of the institution, founded in 1822 as the Société générale des Pays-Bas. It was based in the elegant, enlightenment-age townhouse of the Abbey of Averbode in Rue Montagne du Parc, a short street off Rue Royale leading east towards the Parc de Bruxelles. Wellington was said to have stayed there before the Battle of Waterloo.

Corner views of BNP Parisbas now

The bank’s mission was to exploit the return of peace in order to encourage the growth of industry in the new United Kingdom of the Netherlands, inspired by and in competition with Great Britain. It pursued this mission after Belgian independence in 1830 as the Société générale de Belgique. The historic building was demolished in the 1960s but number 3, rue Montagne du Parc remains the official address of the bank, mid-way between the palace and the national parliament.

The roots of ING Belgium also lie in the 19th century, when Samuel Lambert set up in Rue Neuve as agent for the Rothschilds. The Banque Lambert managed private fortunes, not the least of which was that of King Leopold II’s earnings from his private empire the Congo Free State, officially established in 1885. That same year, the Lambert family acquired a mansion in sight of the Royal Palace on the corner of Avenue Marnix, to act as both residence and headquarters for their business. To this day, Leopold II’s statue sits on the opposite side of the road, midway between his home and his bank, his gaze fixed on the latter.

Over the decades, as Belgium thrived, with early industrialisation followed by colonial wealth, both banks expanded from their initial makeshift bases in aristocratic mansions. Eliminating their 18th and 19th century neighbours bit by bit, by the 1990s each had swallowed up their respective city blocks entirely and were fronted by uncompromising modernist monuments to Belgian finance.

Over the past 25 years, however, each bank has passed into foreign hands. And while one HQ has been erased as an eyesore, the other is the poster child for a new strategy of reinventing Brussels as an open-air museum for the finest post-war architecture.

Location, location, location

To investigate how this happened we need to examine the challenges faced by ageing large commercial buildings. One is endemic, the topography of the city, while the others are more dynamic, including the organisation of workplaces, regulatory norms and the evolution of taste. The BNPPF HQ sits in a location with a centuries-long history of intense occupation, in a hollow just inside and below the first city wall from the 13th century. The Lambert building meanwhile sits in what was a long hinterland, just outside the second city wall from the 14th century.

An 1850 aerial view of Brussels shows the complexity of the first site, a tangle of ancient streets and staircases linking the former court area around Place Royale with the cathedral and lower town, while the second is a vacant plain to the east of the boulevards that replaced the second medieval wall.

The Sisyphean task of Brussels planners now and throughout history has been to compensate for the change in altitude between the lower and upper towns to allow a gentler ascent. A key solution, decided in 1903, was the creation of Rue Ravenstein, a curved ramp supported by concrete stilts lifting the route from the downtown above those medieval alleys. Between the Bozar building and the 15th century mansion that gives the street its name, you can look down on the Rue Terarken, a surviving example of those alleys, giving a glimpse into the complexity of the site.

The BNPPF’s ancestor took advantage of the new street to extend its footprint down from its original building near the park with an annexe. The new building featured a long, traditional stone façade, embracing the curve of Rue Ravenstein. In the 1960s another opportunity arose when Brussels started work on an underground metro system. The city planners seized the opportunity to ease tunnelling between Central Station and the Parc de Bruxelles by permitting the bank to demolish the entire block and update its by-now ageing accommodation.

For a modernist like Van Kuyck, the timing could not be better, and the result of the revolutionary mood in the air was the twin towers on Rue Ravenstein. Conservatism prevailed on the Rue Royale side of the site, however. With the neoclassical terraces lining the park, one of the few non-negotiable features of Brussels heritage, Van Kuyck and his team rebuilt these as a paraphrase of the demolished 18th century mansions.

BNP Parisbas seen from the top of Mont des Arts

When a half-century of use elapsed once again in the 2010s, the bank decided to update its offices. This time, it bowed to the sensitivities of the inner-city site and chose a design aimed at playing nicer with its elegant Art Deco neighbours on rue Ravenstein, including Alexis Dumont’s 1931 Shell building and Victor Horta’s 1922 Bozar. Both of these buildings had been subjected to strict height restrictions to preserve the view from the palace.

Shell was forbidden its desired 22-storey tower, and further up the hill, the squat Bozar appears to have been hammered into the ground. The building’s parapet has a curious sawn-off appearance, as if in mute protest at the enforced diminution (before designing the complex, Horta spent years in the US lecturing on historic architecture of Belgium but all the while falling under the spell of the skyscrapers of Manhattan).

From the park and Rue Royale, the Bozar’s roof terrace resembles a vacant lot while the interior spirals downwards several storeys to its concert hall, which sits at the original level of the quarter. During intervals, orchestra members can be observed taking cigarette breaks in the medieval Brussels of Rue Terarken.

Timing is everything

Serendipity for developers comes in many forms. For the Société Générale de Banque in 1965, it had been the metro project and the radical mood in architecture that had seen the Maison du Peuple torn down that same year, to be replaced with a concrete box. For the Lambert family, the sparks were a small fire at their ageing mansion, the age of the urban expressway ushered in by Expo 58 and the chronic social decline of the Leopold Quarter.

A once homogeneous area of mini-palaces and grandiose townhouses for a landed and rentier class attended by small armies of servants, the area’s fate had been sealed by the arrival in the 1920s of Michel Polak’s towering Résidence Palace at its eastern extremity. Vast, centrally-heated and sunlit serviced apartments reached by elevator were a compelling alternative to the endless stair-climbing of the cavernous, chilly stone boxes of the mid-19th century ("whitened sepulchres”, as US ambassador Brand Whitlock recalled them in his memoir of pre-WW1 Brussels high society).

In a pincer movement, the Banque Lambert that rose from the ashes at its southwestern fringe would sound the death knell for the area. Its name fell out of use in favour of ‘EU Quarter’, now synonymous with the glass, steel and concrete face of administration.

Thus the new Banque Lambert building would set the visual tone for its neighbourhood rather than defy it, as Van Kuyck and partner Jean Polak did for the rival bank across the park. Baron Léon Lambert had wanted Le Corbusier to design his new bank but the grand architect didn’t want to spend the necessary time in Belgium.

Leaving a last dramatic mark on the Brussels landscape, the by-then nonagenarian Belgian pioneer of modern design, Henry van de Velde, suggested Skidmore, Owings and Merrill as an alternative. Their chief architect Gordon Bunshaft accepted the challenge and persuaded the baron to acquire the entire block fronting Avenue Marnix.

With metal for construction then in short supply in Europe, the initial plan for all-steel façade was out of the question, so Bunshaft designed a load-bearing lattice exterior encased in prefabricated concrete. Seizing the attention of passers-by, this vast screen of sculpted, cruciform elements wrings the most out of the scarce Belgian sunlight thanks to the generous western exposure afforded by the esplanade of the palace opposite. Stainless steel articulations between these elements added a touch of luxury.

Inside, meanwhile, the building was designed from the beginning to house Baron Lambert’s art collection, spread across the public areas on the ground floor, the executives’ offices higher up and, at the summit, decorating the Baron’s vast penthouse residence. “I like to think that if Lorenzo de Medici came back and saw this, he would say, ‘This is the way I would do it now,’” Lambert told Time magazine in 1965.

Modernism in the 2020s

In the late 1980s, fresh demolitions allowed an extension in an identical style to be added behind the original Bunshaft block, creating the present H-shaped form. Finally, an irregular city block of 19th century houses behind the site on Rue de l’Esplanade was demolished and replaced with the ING Park, the private property of the bank, creating an additional esplanade from which to view the second replica façade to the rear.

Behind the facades, at the time of writing, the Lambert/ING building is undergoing a profound conversion to reflect current working practices and improve its environmental performance. The architects, A2M, claim that an innovative treatment for the concrete will extract harmful nitrogen oxides from the city air. Public access will be improved thanks to a new “super duplex”, merging the ground and basement floors with access from a new entry on the boulevard leading through the entire site. For A2M, these ambitions for its ING Belgium project “send a strong message to the real estate market: if a retrofit to a listed landmark is allowed to go that far, there should be no excuses when it comes to new build.”

Across the Parc de Bruxelles, behind the horizon defined by the row of replica neoclassical townhouses on the rue Royale, 300 concrete columns wrap the new-build BNPPF HQ into its home on the steep escarpment below. It is of a similar height to its 1910 ancestor, whose street line it restores when viewed from above (this can be observed thanks to the Bruciel online archive of aerial photographs). At street level meanwhile, it resembles a giant Venetian blind sprawling on its side. Like a permanent art installation, it needs to be walked around.

Headquarter of the former Générale de Banque, before it was pulled down in the 1960s

Approached coming uphill from Central Station, its roofline curves to meet that of Dumont’s Shell building opposite to form a dramatic collage of concrete, stone and sky. Viewed straight on at the apex of the curve, the effect is one of lightness and finesse. The passer-by can detect the second, glass façade glinting from behind the delicate ribs of the exoskeleton. When seen from the tourist viewing hotspot Mont des Arts however, the impact is quite different. The louvres of the blinds appear to be closed and the building snaps shut, taking on a heavy, defensive form as if the old city wall has risen again. Rue Ravenstein appears to be a dead end, blocked off by an immense hangar.

BNPPF new Ravenstein facade next to the Shell building of 1931

For Dietmar Eberle of the Austrian firm responsible for the design, Baumschlager Eberle Architekten, “the facade is very much a Belgian façade, very strange” thanks to “different shapes where we open the concrete and where it is closed.” While the Van Kuyck building it replaced was “not bad…not good, it was a document of its time,” he told BX1’s Archiurbain programme.

Thierry Jacqmin, head of BNPPF’s real estate portfolio said the company opted for demolition because a renovation posed too many problems, both in terms of energy performance and sustainability and for the organisation of a modern workplace within the physical constraints of an older building. The external appearance of the new bank “is also a very clear expression of our time,” Eberle commented: “the facade becomes much more an abstract skin, where behind the skin different developments are possible.”

The transience of the permanent

In late 2022, the new building hosted an exhibition, Institutions and the City, exploring the challenges faced by large, institutional buildings implanting themselves within the topography of Brussels. Like its exterior and the voids of the patios sprinkled within its perimeter, the interior shuns the straight edge. The public exhibition rooms form a spare, raw space with a recycled and recyclable feel. This modular, disposable interior replaces the one created for the 1960s building by Belgian designer Jules Wabbes as a permanent and total work of art.

Wabbes, who worked on aircraft interiors for Sabena at the onset of the jet-set age, specialised in the brass and earth tones of his period. This was displayed most sumptuously perhaps in his design for the also-vanished Drugstore Louise, a 1963 address where the cosmopolitan youth of Brussels once queued out the door.

Half a century later, in 2013, design-minded Brusseleirs flocked to a retrospective of Wabbes interiors at the Bozar next door, shortly before the bank decided to demolish one of them a few steps away. A fragment of one of his signature wafer-like ceilings can be seen still by looking up in the Dekkera bar in Saint-Gilles. Architectural salvage specialist Rotor DC still has exquisite bronze and stainless steel handrails and doors from his work for the building available on its website.

When BNPPF announced its decision for a demolition-rebuild in 2014, the urbanist and former Brussels alderman for heritage Henri Simons criticised the loss of a “building exemplary of its period and particularly well executed which was much better integrated within the city than one might think.” For Simons, the new HQ must be regarded as a development project: “the investor isn’t reducing the scale to make fewer square metres. There will be more. Always more.” And by returning to the 1911 street line, “a larger footprint taking up more public space.” To make way for a structure that could have been built anywhere in Brussels, the authorities, “haunted by the black twin towers”, declined to recognise the heritage value of the destroyed building, Simon suggested.

Heritage ain’t what it used to be

By inviting the public to name their favourite postwar buildings, the Brussels Region has recognised that its citizens are also ‘haunted’. Haunted by demolitions, the loss of familiar views, tunnels, viaducts and the urban expressways that eliminated the tree-lined avenues that were once part of the distinct character of Brussels. By top-down decision-making erasing swathes of popular memory. By Brusselization, in short.

And as is the case for the ceilings, handrails and doors of the old BNPPF building and the reborn ING HQ, a heritage salvage exercise is required, both literal and psychological. With the public getting a say over what gets hauled into the lifeboat with the churches, the guild houses, the crow-step gables and the art-nouveau sgraffites. Nudged along by a newer generation of academics and public tastemakers entrusted with the fate of the artistic production of the recent past, even when it doesn’t look like art.

Heritage ain’t what it used to be. In the words of Henri Simons: “In the 1960s, we destroyed Art Nouveau like Horta’s Maison du Peuple, today we destroy the important modernist creations of Van Kuyck, Polak and Wabbes. Why make the same mistakes again?”