Contemporary Belgian politics often seems too complex for its good, but the political landscape in the Middle Ages and the early modern period could have been even more bizarre. Belgium was once a patchwork of semi-independent duchies, counties, lordships and most puzzling, a principality ruled by a bishop.

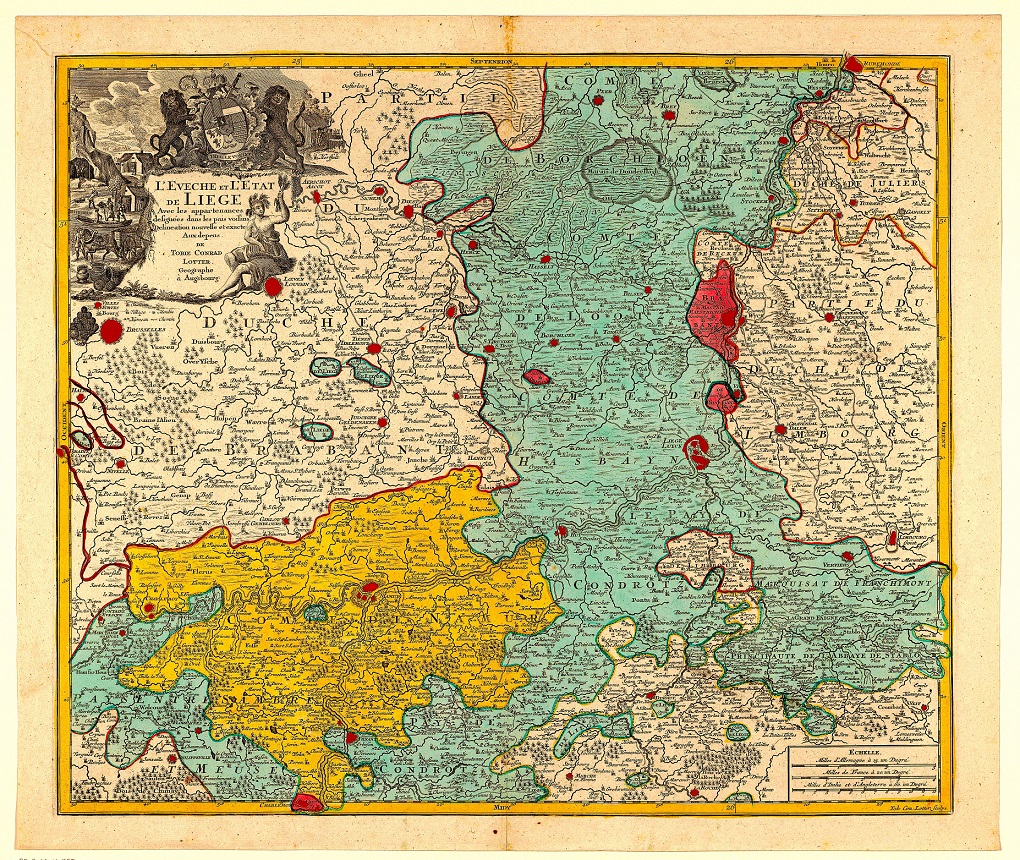

Known as the Prince-Bishopric of Liège, it endured for some 800 years and sliced the Habsburg Netherlands in half – although an accurate map of the region would look less like an orange peel and more like a blood splatter. The state was a vassal of the Holy Roman Empire and subject to the Pope’s authority in Rome but mostly chartered its own course.

The prince-bishopric emerged around 980 when the bishop of Liège, Notger (or Notker) seized the counties of Hoei and Bruningerode, thus merging his episcopal duties with those of a worldly prince. This situation was not unique at the time, though: the Pope was both the head of the Catholic Church and the ruler of the so-called Papal States.

Liège effectively turned into an elective monarchy. The prince-bishop was elected by the members of the influential St Lambert’s Chapter and governed until he died – which could be of natural causes or if political adversaries cut his life shorter.

Notger was the first in a long line of prince-bishops. He left his mark, rebuilding the cathedral of St. Lambert and the episcopal palace, and completing the collegiate church of St Paul. Contemporaries said he turned his capital into the Athens of the North, a centre of learning buzzing with new ideas and countless scholars. A mantra emerged to honour him: “Liège, tu dois Notger au Christ et le reste à Notger,” which translates as, “Liège can thank Christ for Notger and Notger for everything else.”

Constitutional contortions

Liège was also a test case for constitutional innovations. It pioneered the principles of rule of law through a contract between the sovereign and his subjects long before the Magna Carta was signed in England. It already set some new standards in 1066 when Prince-Bishop Dietwin granted city rights to Hoei, which became one of the first free cities in medieval Europe.

Notger

The unwieldy dual fealty to the Holy Roman Emperor and the Pope sometimes created problems. After Albert of Leuven was elected Prince-Bishop in 1191, Emperor Henry VI manoeuvred to replace him with Lothair of Hochstadt. Albert was only confirmed when the Pope intervened to recognize him. He was consecrated but murdered by German knights in Reims in 1192. In 1195, Albert van Cuyck claimed the mitre after convincing the Pope to annul the 1193 election of the-then Prince-Bishop Simon.

But although Liège was both a bishopric and a principality, it was like other monarchies in Europe in seeking ways to expand its territory. Its biggest success was in the 1360s when it incorporated the County of Loon, nowadays roughly the Belgian province of Limburg.

The system developed constitutional innovations: in 1316, Prince-Bishop Adolph of the Marck issued the Peace of Fexhe that set out individual freedoms and established a proto-parliament called the Sens du Pays, or Estates of Liège. But under mounting pressure from the nobles, he was forced in 1343 to install the Tribunal of the XXII, a court designed to settle conflicts between aristocrats and protect citizens against arbitrary state action.

If Liège’s arrangement wasn’t weird enough, it was involved in another political quirk, the Two Lordships of Maastricht. The city on the Meuse or Maas was governed by both the Duke of Brabant (later replaced by the Dutch Republic) and the Prince-Bishop of Liège. Dating from the 13th century, this arrangement meant Maastricht had two mayors, two sets of civil servants and judges representing different rulers, and two religions (Protestantism and Catholicism).

Cockpit of conflict

Liège also saw its fair share of political upheaval and drama. The most infamous episodes centred on the question of whether Liège was part of the Burgundian sphere of influence.

In 1408, John I of Burgundy, also known as John the Fearless (Jean sans Peur , Jan zonder Vrees) led an army to fight the nobles and burghers of Liège after his wife’s second brother, John of Bavaria, had been overthrown as Prince-Bishop in favour of Diederik of Perwez. With his knights on horseback and Scottish archers, John the Fearless annihilated the Liège rebels at the Battle of Othée, and afterwards, had all Liège notables beheaded or drowned in the Meuse.

There was further turmoil in 1456, when 18-year-old Louis of Bourbon was elected Prince-Bishop, mainly thanks to his uncle, the Duke of Burgundy Philip the Good. The arrival of the inexperienced Louis would trigger the Wars of Liège as citizens rose up against Burgundian domination, forcing the Prince-Bishop to flee. Charles the Bold, Louis’s father, who had then become Duke of Burgundy, laid siege to Liège in 1468, accompanied by the King of France, Louis XI.

Louis of Bourbon

It was during the siege that the 600 Franchimontois made their name with their doomed plan to assassinate the Duke and King: Vincent de Bueren led a night attack over the Saint Walburga stairs against the sleeping Burgundians, but his scheme failed. All 600 were killed in battle or executed and Liège surrendered the next day (the Saint Walburga stairs were later renamed the Montagne de Bueren, and the 374 steps are still a major Liège tourist spot). Charles would punish the city further, tying hundreds of Liége leaders together and throwing them into the Meuse river. The city was set alight and is said to have burned for seven weeks.

As for Louis, although he retained his seat, he was killed in 1482 by Willem van der Marck, the so-called Boar of the Ardennes, in a bid to replace him with his son Jean de la Marck. Van der Marck failed – the next prince-bishop was John of Hornes – but his cousin Everhard would be appointed Prince-Bishop in 1505 and commissioned the construction of the vast Renaissance-style Palace of the Prince-Bishops in central Liège, which currently serves as a courthouse.

Weapons, wealth and a revolution

Liège was also a huge weapons market for the great powers. One arms maker was Jean Curtius who had a monopoly on selling gunpowder to the Spanish army. When he died in 1628, he was one of the richest men in the land, hence the local expression, riche comme un Curtius de Liège (rich as a Curtius of Liège). His grand palatial mansion in Liège is now a museum.

There was a measure of stability for almost two centuries, between 1581 till 1763, when most prince-bishops belonged to the Bavarian Wittelsbach family, which also provided the prince-bishops in other such territories, like in Cologne, Freising or Regensburg.

The complex map of the Prince Bishopic of Liège

But the system began to unravel at the end of the 18th century. Inspired by the principles of the Enlightenment, François-Charles de Velbrück, elected in 1772, set up the Société Littéraire de Liège (the Literary Society of Liège), introduced more state-funded schools and added physical and human sciences to the curriculum.

César-Constantin-François de Hoensbroeck, the last Prince-Bishop

But when he died in 1784, his successor, César-Constantin-François de Hoensbroeck, attempted to reverse most of these reforms. Nicknamed the Tyrant of Seraing, de Hoensbroeck’s harsh conservatism ran counter to the mood of the time. In August 1789, just a month after the storming of the Bastille in Paris, a mob marched on the Prince-Bishop’s palace in Liège. De Hoensbroeck fled and the Republic of Liège was established.

In September 1789, again following the French revolutionaries, the new Liège government adopted the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen of Franchimont. It was even more radical than its French counterpart, stressing how sovereignty resides in the people and not in the nation.

But the Republic of Liège lasted just two years. In 1791, Austrian troops reinstalled de Hoensbroeck as Prince-Bishop. He died the following year and was succeeded by François de Méan de Beaurieux, who would be the last Prince-Bishop. The French invaded and annexed it in 1795. De Méan’s consolation price was to become Archbishop of Mechelen in 1817. But the Prince-Bishopric of Liège, which had set constitutional milestones and been at the cockpit of conflict, was no more.